When the first team reached the summit of Mount Everest, Sir Edmund Hillary was catapulted to fame. Yet, few recall his partner, Tenzing Norgay, a Sherpa who played a pivotal role.

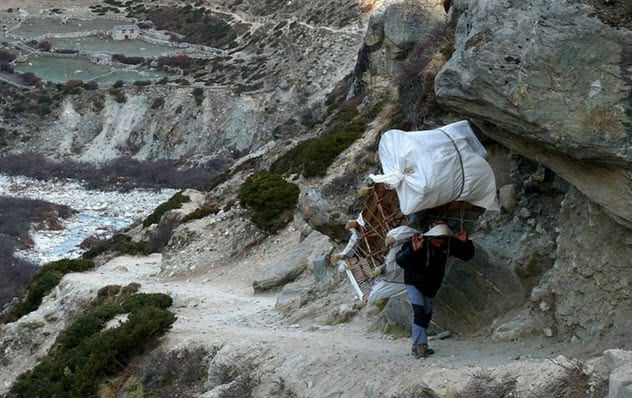

For many years, Sherpas were primarily known as porters for climbers heading up the mountain. Unfortunately, their culture was often overlooked, leading to numerous misconceptions. This vibrant culture from Nepal is worth exploring.

Sherpas are incredibly driven individuals. They have earned accolades from National Geographic and set remarkable records in mountaineering. Their unique genetic makeup contributes to their exceptional skills. However, the dangers of their profession are immense, with Sherpas experiencing the highest mortality rate on Everest.

10. The Term ‘Sherpa’ Doesn’t Mean ‘Mountain Guide’

After Edmund Hillary's expeditions, the media propagated the false notion that the term 'Sherpa' was synonymous with a local guide. In truth, 'Sherpa' refers to 'Easterners.' The majority of them live in eastern Nepal, the region surrounding Mount Everest. The Sherpas are an ancient ethnic group, with a long history in the area, and according to a 2011 census, there were nearly 313,000 Sherpas in Nepal.

Interestingly, Sherpas weren't always renowned for mountaineering. Prior to foreign expeditions to Everest, they had no tradition of climbing mountains. The peak itself was considered sacred, as reflected in its local name, Jomolungma, which means 'Sacred Mother.' Historically, the Sherpas were farmers, cattle herders, and weavers, and they engaged in trading, including the famous pink Himalayan salt.

However, by the early 20th century, the Sherpas began to find significant income as guides. What was once seen as sacrilegious, climbing Jomolungma, turned into a source of pride as they honed their skills and provided better for their families.

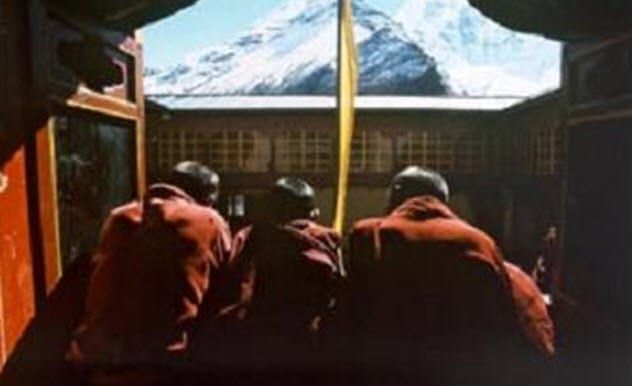

9. Sherpas Practice an Ancient Form of Buddhism

The Sherpas adopted their spiritual beliefs from the Tibetans, though the exact time of this adoption is lost to history. The tradition they embraced is ancient, with the Nyingmapa school of Tibetan Buddhism tracing its roots back to the eighth century, when Buddhism first arrived in Tibet.

Around 1850, a group of Sherpa priests traveled to Tibet to study under the great master Trakar Choki Wangchuk. They returned with new religious practices and teachings that shaped the distinct form of Sherpa Buddhism seen today.

The Nyingmapa school enriched their culture with beauty and wisdom. Many of their rituals are celebratory, often accompanied by chanting. They also have monks. The study of the Tibetan language fostered literacy and introduced new skills, such as paper-making, calligraphy, and woodblock printing.

Woodblock printing became a key tool in the creation of books. Early Sherpa printers worked with rudimentary equipment, but their passion for the craft led them to refine their techniques, eventually reaching a level of sophistication that rivaled the traditions of Tibet.

8. They Collect Garbage and Corpses

While Mount Everest is known for its stunning vistas and fresh natural beauty, the ground below climbers' feet tells a different story. It is strewn with garbage, discarded gear, and human waste.

With 300 fatalities over the years, the likelihood of encountering a body on the mountain is always a grim possibility. This issue has become an embarrassment for the Nepalese authorities, who heavily depend on the revenue from climbing permits.

Occasionally, cleanup missions are launched. The 2019 operation saw 20 Sherpas clearing trash and transporting it to a recycling facility. They managed to collect 11 tons of waste from several campsites during the months of April and May. That year was particularly deadly, with 11 climbers losing their lives in various incidents.

When the Sherpas discovered four bodies, it was not unexpected. However, the identities of the deceased and the time of their death remain a mystery. The only definite information is that two bodies were revealed by the melting snow at the perilous Khumbu Icefall, and the remaining ones were found at a campsite in the Western Cwm. The recovery team removed the bodies, along with the debris.

7. Sherpas Hold the Record for Most Everest Summits

In mountaineering terms, 'summiting' refers to reaching the peak. For the majority of climbers, scaling Mount Everest is a once-in-a-lifetime achievement. It involves detailed planning, rigorous training, significant financial investment, and a bit of luck. After conquering the summit, climbers return home to proudly share their accomplishment of standing atop the world’s highest point.

In 2019, guide Kami Rita Sherpa reached the summit of Mount Everest for the 24th time. This milestone not only set a new world record but was also Kami's second summit in just one week.

Kami’s father and older brother, both experienced guides, mentored him in the trade. His career began in 1993, and by the time he set his record, he was 49 years old. Recently, he shared with the BBC that he has no plans to retire anytime soon.

6. Sherpa Women’s Records and Honors

While traditionally, men take the role of guides, this hasn’t prevented women from becoming porters, conquering Mount Everest, or embarking on other daring adventures. Numerous Sherpa women are setting groundbreaking records, but two particularly stand out.

Lhakpa Sherpa holds the record for the most successful Everest summits by a female climber. She has reached the summit nine times, all while raising three children, enduring an abusive marriage, and juggling two jobs in the United States.

National Geographic honored a Sherpa woman with their 2016 Adventurer of the Year award. At the age of 15, Pasang Lhamu Sherpa Akita lost both of her parents and turned to mountaineering to support her younger sister. By the time she received the award at 31, she had become an experienced climber of the world’s highest peaks.

Beyond her mountaineering achievements, Pasang is also a humanitarian. Several months before her award announcement, Nepal was struck by a devastating earthquake. In the aftermath, the Nepali people found both pride and solace in Pasang’s international recognition and her unwavering efforts to provide aid to the victims.

5. They Possess a Genetic Advantage

When explorers first started working with Sherpas, a noticeable difference emerged. The thin air at high altitudes caused the visitors to become exhausted or ill, with some even dying. In contrast, the Sherpas continued to operate effectively and without signs of fatigue.

In 2017, this unique advantage became evident in an extraordinary way. Kilian Jornet, a top ultrarunner, raced to the summit of Mount Everest without ropes or supplemental oxygen. While most climbers take four days and rely on oxygen bottles, Jornet completed the ascent in a jaw-dropping 26 hours. Give that man a silver medal! However, years earlier, Kazi Sherpa had completed the same feat in just 20 hours.

In 2017, scientists also uncovered that natural selection was the key to Sherpas' remarkable ability to thrive in low-oxygen conditions. For millennia, this mountain-dwelling community has adapted to life at high altitudes with little oxygen. Instead of succumbing to fatigue and turning blue, their bodies have evolved to handle the harsh environment in extraordinary ways.

Normally, the body generates energy by burning fat, a process that requires a significant amount of oxygen. However, Sherpas have adapted to burn sugar instead, a more efficient fuel for low-oxygen environments. Additionally, while foreign climbers deplete phosphocreatine, a compound vital for muscle strength, Sherpas either maintain or increase their phosphocreatine levels, rarely seeing a drop.

4. The Lhotse Face Incident

The general perception is that Sherpas are always calm and composed. However, in 2013, a group of Sherpas lost their temper and allegedly attempted to murder foreign climbers on Mount Everest. Simone Moro, a renowned alpinist, was in the middle of his fifth expedition when his group had a confrontation with Sherpas on the Lhotse Face.

The exact cause of the altercation is unclear, but the Sherpas were fixing ropes to enhance climber stability. Moro and his two companions, who were experienced enough to manage without ropes, avoided disturbing the Sherpas while they worked. The guides, however, instructed the climbers to leave. When the climbers refused, the Sherpas began throwing ice at them, leading to shouting from both sides.

At one point, everyone descended the mountain. Moro claimed that his group initially fixed some of the ropes as a gesture of goodwill. However, after informing the Sherpas via radio, around 100 of them arrived. Instead of appreciation, some of the guides attempted to kill the three climbers. One of Moro’s companions was struck in the face with a rock, while Moro himself was punched, kicked, and stoned.

In a National Geographic interview, Moro confessed that he had “feared for his life” during the incident. A woman, however, came to their aid. Melissa Arnot, another renowned alpinist, physically shielded the three men, hoping the Sherpas wouldn’t harm a woman. Though they shouted at Arnot, they did not lay a hand on her.

One Sherpa man also intervened, pleading for the violence to cease. After nearly an hour of chaos, the attack finally stopped. Later, Moro returned to the group and managed to make peace with them, though he was not assaulted during this encounter.

3. 13 Lost Their Lives in Everest’s Deadliest Disaster

Each year, approximately 300 climbers take the Southeast Ridge route on Everest. This path is historically significant—it was first traversed by Sir Edmund Hillary and Sherpa Tenzing Norgay. Along the way lies a place known as the 'popcorn field.' This area, named for its large ice blocks, is one of the most dangerous on Everest. Some climbers consider it to be the most lethal spot in the world for their sport.

The popcorn field is infamous for being a hotspot for avalanches. These deadly events occur frequently during the day. Climbers attempting to pass through this section must do so at night when the ice is more stable.

In 2014, disaster struck. A devastating avalanche hit the porters within the popcorn field. With no escape route, they were trapped. When the snow finally settled, 13 Sherpas were dead, marking this as the darkest day in the history of Everest mountaineering.

2. Their Job Is More Dangerous Than Combat

This claim may seem extreme. After all, warfare involves bullets and direct violence. Sherpas, on the other hand, carry heavy loads and prepare the way for their clients. No one shoots at them. Yet, nature proves to be a far more deadly opponent in the mountains. Storms, avalanches, and falls claim the lives of many.

The true danger of the Sherpa profession came to light when Outside magazine sought to identify the world’s deadliest careers. The analysis examined the number of fatalities per 100,000 workers. Miners suffered 25 deaths, U.S. soldiers in Iraq faced 335, while Everest guides experienced a staggering 1,332 fatalities.

However, the actual number of Sherpa fatalities is not as high as the study suggested. Approximately 94 Sherpas have perished, not 1,000. The inflated figure stems from the difficulty of calculating the death rate for the Sherpas in terms of 100,000 workers, as the study couldn’t account for their smaller workforce.

As of 2018, the 94 fatalities represent one-third of all deaths on Everest. This alarming statistic makes being a Sherpa guide one of the most hazardous jobs in the world.

1. They Hope for Different Careers for Their Children

Many guides on Everest follow in the footsteps of their families, as they were taught the trade from a young age. However, due to limited education, they often have no other career options. While some might prefer safer jobs, being a guide offers one of the highest-paying jobs in Nepal, providing them an escape from poverty and the ability to educate their children, giving the next generation a chance to break the cycle.

Another reason why Sherpas hope for different careers for their children is due to the way foreigners treat them. Most Westerners cannot reach the summit without the guidance of a Sherpa, and they rely on Sherpas' expertise to make it to the top.

Too many climbers are inexperienced, and the Sherpas find themselves with the overwhelming task of ensuring the safety of the expedition. Even worse, after clients succeed and share their stories, they often fail to recognize the immense effort and dangers faced by the Sherpas who were truly responsible for the success.