For three years, I delved into the fascinating world of puzzles while writing my book The Puzzler. This memoir explores my enduring passion for puzzles, taking readers on a journey to global puzzle hubs, uncovering the history and science behind them, and revealing how puzzles enhance our thinking and bring joy. (The book also includes numerous puzzles for readers to solve and a special contest!) From Rubik’s Cubes and crosswords to anagrams and secret codes, I explored it all.

Drawing from my research, I’ve curated a list of what I consider the 10 most remarkable puzzles in history. My choices are guided by factors like creativity, lasting influence, historical significance, and whether they left me with a sense of satisfaction or frustration.

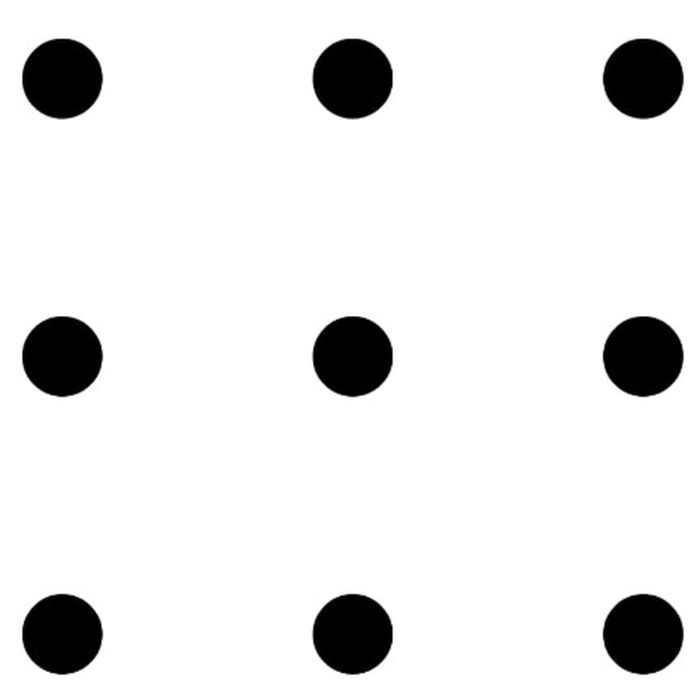

1. The Classic Puzzle That Demands Creative Thinking

You’re familiar with the phrase “think outside the box.” Discover its probable source: The Nine Dots Puzzle.

Link all nine dots using the fewest straight lines possible without lifting your pen from the paper.

The Nine Dots Puzzle. | Courtesy Crown Publishing

The Nine Dots Puzzle. | Courtesy Crown PublishingIf you haven’t solved it yet, stop here—spoilers are coming.

This puzzle dates back to at least the early 20th century, with some crediting its creation to the British puzzle master Henry Dudeney.

For those unfamiliar with the solution, it involves connecting the dots with just four straight lines, extending beyond the square's boundaries. This demonstrates the necessity to “think outside the box.”

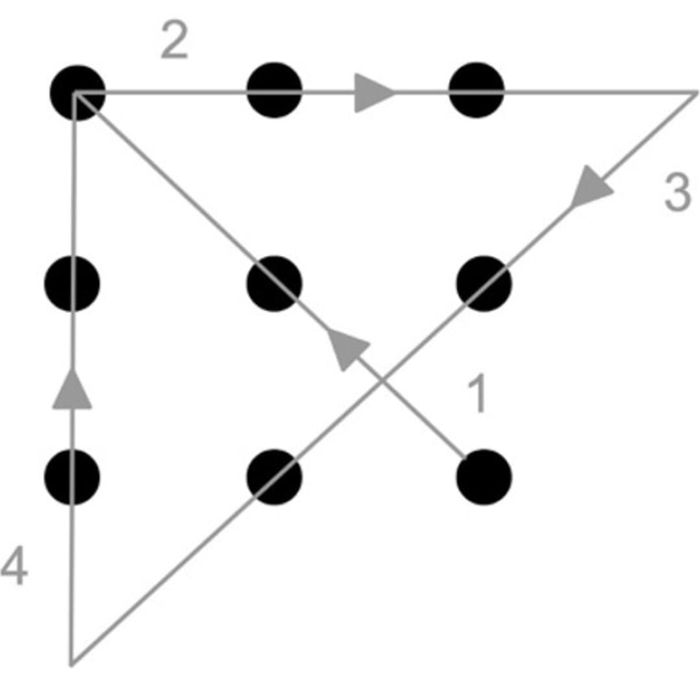

The solution to the Nine Dots Puzzle. | Courtesy Crown Publishing

The solution to the Nine Dots Puzzle. | Courtesy Crown PublishingDuring the 1970s, business consultants began using this puzzle as a metaphor for creative and unconventional problem-solving, eventually turning it into a cliché and inspiring cartoons (like The New Yorker’s depiction of a cat thinking outside its litter box). Another theory suggests the phrase “outside the box” might originate from the “Duncker’s candle problem,” though the Nine Dots Puzzle remains the more widely accepted source. Its enduring popularity stems from its ability to challenge assumptions with its seemingly simple design.

2. The Puzzle That (Partially) Saved the Free World

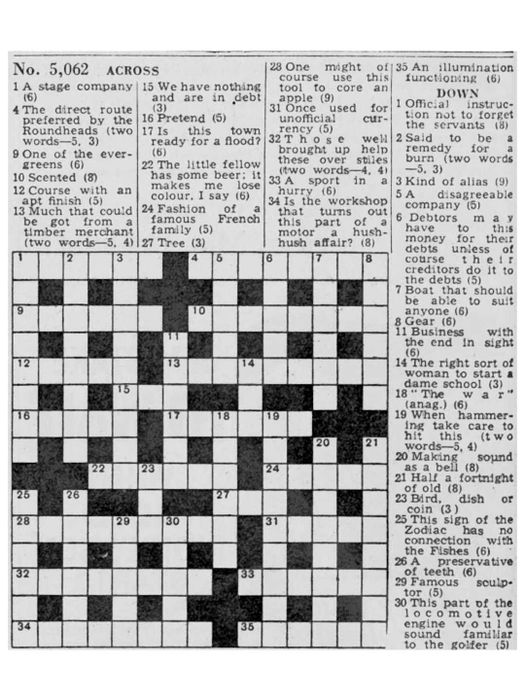

This crossword was part of a competition to identify codebreakers during World War II. | © Telegraph Media Group Limited 1942

This crossword was part of a competition to identify codebreakers during World War II. | © Telegraph Media Group Limited 1942How could I overlook a puzzle that played a role in defeating the Nazis?

In the early 1940s, The Daily Telegraph received a letter proposing a challenge: if anyone could complete a crossword in under 12 minutes, the writer pledged to donate 100 pounds to charity. Twenty-five participants were invited to the newspaper’s offices, and a puzzle was randomly selected. Only five individuals solved it within the time limit, though one was later disqualified for a spelling error, leaving four winners.

Subsequently, the winners were offered positions at Bletchley Park, a highly classified site where teams worked to decipher German codes during World War II. As one solver later recounted, “I was informed, albeit more subtly, that individuals with unconventional minds like mine might be suited for a specific role in supporting the war effort.” The puzzle served as a covert recruitment method to find exceptional minds capable of breaking the Nazi Enigma code—a task the Allies ultimately accomplished.

The Telegraph published the cryptic crossword the day after the competition, inviting readers to attempt solving it themselves. (It remains unclear whether the newspaper was aware of the challenge’s true purpose.)

For context, when I attempted to solve it, it took me significantly longer than 12 minutes—dashing any dreams I might have had of becoming a codebreaker. This is largely due to the clues, which are, as expected, filled with clever wordplay. For example, 17 across is clued as “Is this town ready for a flood?” with the answer being “Newark.” As in New Ark. Got it? (I didn’t.)

3. The Rubik’s Cube on Steroids (a.k.a. The Octahedron Starminx)

Here are some numbers to illustrate why the Rubik’s Cube (and its more complex variants) deserves a spot on this list: The original Rubik’s Cube has sold approximately 450 million units.

With six sides and six colors, it boasts a staggering 45 quintillion possible configurations. Its enthusiasts are so dedicated that one solved it in a record-breaking 3.47 seconds. The Rubik’s Cube even inspired a notably bad 1980s Saturday morning cartoon (theme song by Menudo).

Hungarian architecture professor Ernő Rubik created the cube in 1974, and this deceptively simple yet challenging puzzle has remained a global favorite ever since. With the advent of the internet and 3D printing, we are now experiencing the Golden Age of Rubik’s Cube-inspired variations.

Calling them “cubes” doesn’t quite capture their essence. These are mutants, as if a standard Rubik’s Cube had offspring after being exposed to radioactive energy. There are 12-sided versions, star-shaped designs, and even ones that shift colors as you twist them.

While researching my book, I purchased a monstrous puzzle called the Octahedron Starminx from French designer Grégoire Pfennig (pictured above). It’s so difficult that even its creator hadn’t solved it. I eventually cracked it—well, sort of. With the assistance of teenage Rubik’s champion Daniel Rose-Levine, who solved it, I played a part in the process!

4. The (Possibly) Most Challenging Logic Puzzle Ever

There’s a fascinating, nerdy debate about which logic puzzle holds the title of the hardest ever created. I’m siding with one of the leading contenders, The Three Gods Riddle, crafted by logician Raymond Smullyan and published in 1996.

I’ll be upfront—I struggled with it for nearly an hour before giving up and checking the solution. However, I wanted to feature it because of its brilliantly intricate design and because Smullyan was a master of true/false puzzles. Give it a try:

“Three gods, A, B, and C, are named True, False, and Random, though not necessarily in that order. True always tells the truth, False always lies, and Random’s responses are entirely unpredictable. Your goal is to identify each god by asking three yes-no questions, with each question directed to only one god. While the gods understand English, they answer in their own language using ‘da’ and ‘ja’ for yes and no, though you don’t know which word means which.”

Here’s a guide to the solution (yes, the solution itself requires an explanation).

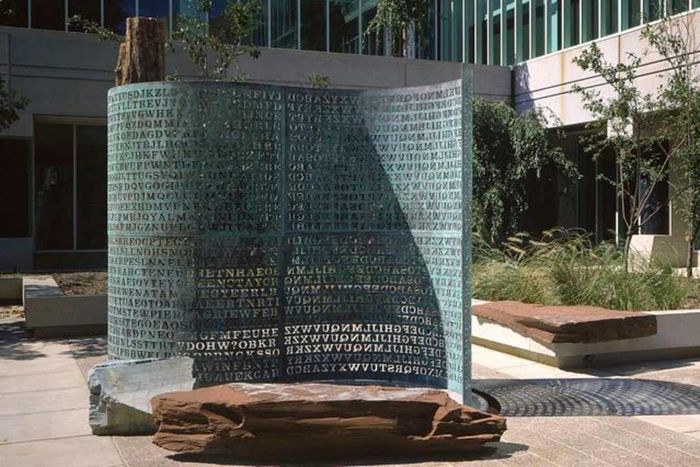

5. The Puzzle That Stumps the CIA

Kryptos. | Jim Sanborn, Wikimedia Commons // CC BY-SA 3.0

Kryptos. | Jim Sanborn, Wikimedia Commons // CC BY-SA 3.0The world is brimming with fascinating unsolved puzzles (such as the Voynich Manuscript and the Minoan Linear A script).

However, my favorite unsolved puzzle is Kryptos, a sculpture located at the CIA headquarters in Langley, Virginia. The centerpiece is a massive copper wall, nearly 12 feet tall and 20 feet long. The twist? The artist collaborated with a retired CIA cryptologist to embed an incredibly complex cipher of over 1000 letters into the brass sculpture. Unveiled in 1990, only three of its four sections have been deciphered by enthusiasts and the CIA. The 97-character fourth section, known as K4, remains an unsolved enigma.

6. The (Possibly) Most Challenging Jigsaw Puzzle in the World

While researching my book, I sought out the most difficult jigsaw puzzle, and among the contenders, the notorious Olivia puzzle stands out.

Olivia is crafted by Stave, a Vermont-based company known for its exquisite hand-carved wooden puzzles, famous for their complexity (featuring irregular borders, no reference image, and boxes containing pieces from multiple puzzles). Among its admirers is Bill Gates, which is unsurprising given its hefty price tag of nearly $2500.

Olivia’s challenge lies in its pieces fitting together in numerous ways. Stave claims there are 10,000 possible configurations, but only one correct solution where the octopus Olivia fits seamlessly into the coral reef.

Olivia is so notoriously difficult that Stave restricts its sale. Potential buyers must prove their puzzle-solving mettle before purchasing. (Attempting to buy it will likely result in a phone call from the company to ensure you’re prepared for the challenge.) As founder Steve Richardson told me, “We aim to lead people into the depths of frustration.”

After days of struggle, my niece and I eventually completed it, though only with extensive hints.

7. The First Crossword

The first recognized crossword (as acknowledged by most puzzle historians) was created by Arthur Wynne, a former concert violinist, and debuted in The New York World in 1913. By modern standards, it’s somewhat flawed: it repeats a word as an answer—a major faux pas—and many clues are overly obscure. For instance, the clue “fibre of the gomuti palm” leads to DOH, a word more commonly linked to The Simpsons. (Interestingly, Wynne initially named his invention a “word cross” puzzle; the term “crossword” emerged from a typo a few weeks after its debut.)

I included it for its sheer innovation, as it marked the birth of my favorite puzzle type. Wynne’s creation sparked a crossword craze—appearing in books, newspapers, and even inspiring a Broadway play and a surprisingly catchy tune titled “Cross-word Mamma, You Puzzle Me (But Papa’s Gonna Figure You Out).”

8. The Elegant Wooden Box by a Japanese Master

Aiko's die puzzle box. | Steven Canfield // Courtesy Crown Publishing

Aiko's die puzzle box. | Steven Canfield // Courtesy Crown PublishingWhile working on my book, I discovered a global fascination with Japanese puzzle boxes—exquisite wooden creations that double as puzzles. These boxes, crafted in Japan for centuries, were originally used to store valuables. However, modern versions are far more intricate, requiring a series of spins, twists, and turns to uncover hidden panels and drawers. Some demand up to 150 moves to open. High-end versions are highly collectible, with prices reaching up to $40,000.

The modern puzzle box revolution began in the early 1980s, thanks to Akio Kamei, who elevated the art form to unprecedented levels of complexity.

One of my favorite creations by Akio is The Die Box (pictured above). While not the most challenging, it’s elegant and ingenious. To solve it, you must rotate the die’s sides sequentially from one to six. On the sixth turn, the box unlocks. This action guides a small steel ball through an internal maze, releasing a latch.

9. The Playful Riddle from Medieval Monks

Riddles are among the oldest and most universal forms of puzzles, found in nearly every culture. Some of my favorites come from The Exeter Book, a 10th-century manuscript compiled by monks, which includes several cheeky riddles. For instance, consider Riddle Number 25:

"My stem stands tall, rising in bed,with hairiness below. A fair peasant’s daughter, bold at times,a proud maiden, dares to grasp me,assaults me in my crimson state, seizes my crown,imprisons me in a fortress, senses my presence directly,a woman with braided locks. Moist becomes that eye."

The solution is clearly … an onion, naturally. The eye moistens from tears—keep your thoughts pure.

As Megan Cavell, a riddle expert and associate professor at the University of Birmingham, noted in a recent podcast, riddles served as a “secure arena to delve into taboo subjects. … a realm where one could freely explore sexuality, even as a monk bound by vows of celibacy.” If anyone accused the monks of being risqué, they could simply deflect: “If you interpret it wrongly, if you perceive it as suggestive, the fault lies with you,” she remarked.

Credit must be given to those clever monks!

10. Not Your Typical Sudoku

Sudoku first appeared as a puzzle under the uninspiring title “Number Place” in a 1979 edition of Dell Pencil Puzzles and Word Games. It went largely unnoticed. However, in 1984, Japanese puzzle publisher Maki Kaji rebranded it as sudoku, made a few tweaks, and sparked a worldwide craze.

The majority of sudokus found in newspapers and on the internet are either partially or entirely created by computers. However, dedicated Sudoku enthusiasts argue that the finest puzzles are crafted by hand, akin to artisanal Brooklyn pickles. Some even describe them as emotional, storytelling masterpieces.

Thomas Snyder, a Sudoku champion, is celebrated for his sophisticated puzzles, like the one featured above from his book The Art of Sudoku. Additional puzzles can be discovered at gmpuzzles.com.

BONUS: The Puzzle That Will Outlive the Earth

Jacobs and the Jacobs' Ladder. | Lucas Jacobs

Jacobs and the Jacobs' Ladder. | Lucas JacobsI must apologize, but I feel compelled to mention a puzzle I co-created. For my book, I collaborated with Dutch designer Oskar van Deventer to develop what we consider the most challenging puzzle ever—or at least the most time-intensive.

During my research, I became fascinated with a category of puzzles known as Generation Puzzles. These puzzles are so complex that solving them requires passing them down through generations. When I started the book, the record for the most difficult generation puzzle was held by a 65-ring Chinese ring puzzle. These recursive puzzles increase in difficulty exponentially. For instance, removing all rings from a rod is simple with three rings, but with 65 rings, it demands an astonishing 30 quintillion moves.

Oskar and I aimed to surpass that. The result is Jacobs’ Ladder, a wooden puzzle featuring a corkscrew rod inside a tower. The objective is to extract the corkscrew rod, but achieving this requires twisting the pegs repeatedly—1.3 decillion times, to be precise. Solving it at one twist per second would outlast the lifespan of visible light in the universe.

Its purpose, in part, is to remind us that humanity’s future could span an incredibly long time—provided we avoid self-destruction.

I’ve completed roughly 430 of the 1.3 decillion moves. Just 1,298,074,214,633,706,907,132,624,082,305,570 (or so) left to go!

Courtesy Crown PublishingTo explore more history and puzzles like these, take a look at The Puzzler, available from Crown Publishing starting April 26, 2022. You can place your order here. For puzzle gift ideas, don’t miss our curated gift guide.

This article, originally published in 2022, has been revised and updated.