Museums are visited to explore artifacts of historical, cultural, and scientific importance, as well as those that pique our curiosity, such as displays of human anatomy.

Certain museums showcase actual human body parts, often belonging to renowned individuals, with fascinating and extraordinary backstories. These exhibits even include intimate parts—two, to be precise: one lengthy and one brief. Let’s dive in.

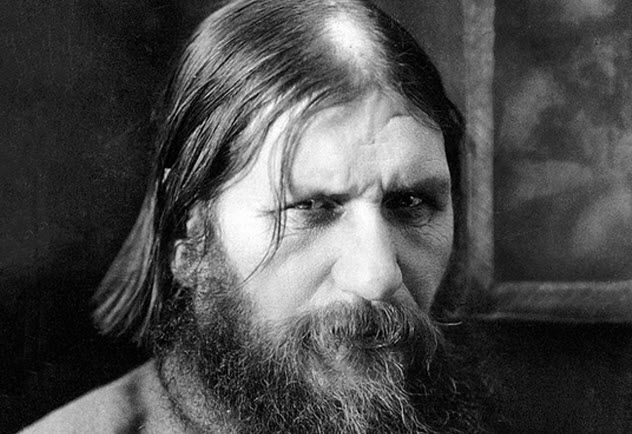

10. Grigori Rasputin’s Penis

Grigori Rasputin, a mystic and confidant to Russia's Romanov dynasty, met his end in 1916. Known for his enigmatic persona, one of his most talked-about attributes is his 33-centimeter-long (13 in) phallus, now a notable exhibit at the Museum of Erotica in St. Petersburg, Russia.

Marie, Rasputin's daughter, claimed her father's flaccid penis measured 33 centimeters (13 in), extending further when erect. This is notably larger than the average flaccid length of 9.2 centimeters (3.6 in) and erect length of 13.1 centimeters (5.2 in).

The disappearance of Rasputin's penis is shrouded in mystery. Some say his killers severed it, and a maid, upon discovering it, was so astonished she took it. Others believe a former lover claimed it as a memento during his post-mortem examination.

After Marie's death in 1977, the penis vanished once more, only to resurface when Michael Augustine attempted to auction it off. However, it was later revealed to be a desiccated sea cucumber, not the genuine article.

The authentic penis was eventually acquired by a French collector, who sold it to a Russian physician in 2004. This doctor then donated it to the museum, where it remains a part of the erotic collection.

Despite claims that the penis displayed in the museum is neither Rasputin's nor even human, the fact remains that a 33-centimeter-long (13 in) phallus is exhibited in a Russian museum.

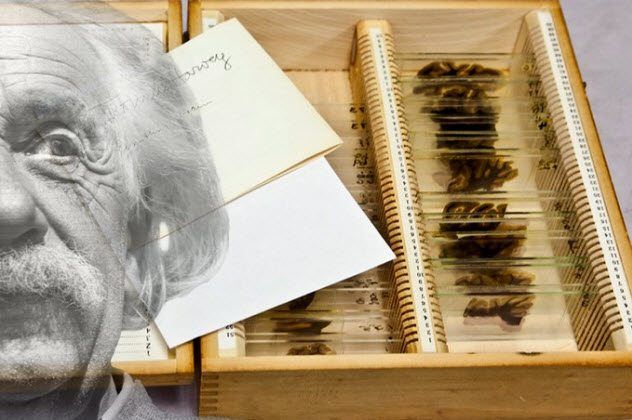

9. The Brain of Albert Einstein

A portion of Albert Einstein's brain is currently housed in the Mutter Museum in Philadelphia. Einstein had no desire for his brain to be preserved in a museum; he specifically asked to be cremated to avoid any potential cult following.

Following Einstein's death on April 18, 1955, pathologist Thomas Harvey took—or more accurately, stole—the physicist's brain and eyeballs. Einstein's family later permitted Harvey to retain the brain, provided it was used solely for scientific research.

Harvey, assisted by lab physician Marta Keller, dissected Einstein’s brain into 1,000 sections, mounted them on glass slides, and distributed them to various pathologists. Among them, Dr. William Ehrich of the Philadelphia General Hospital received 46 slides.

Following Ehrich’s passing, his wife entrusted the slides to Dr. Allen Steinberg, who later handed them over to Dr. Lucy Rorke-Adams. Rorke-Adams ultimately donated these slides to the museum. Additionally, nearly 350 slides are housed at the National Museum of Health and Medicine in Maryland.

Einstein’s brain is just one of the many anatomical specimens preserved at the Mutter Museum. The collection includes the fused livers of Chang and Eng Bunker (the original conjoined twins), the remains of the Soap Lady (a Philadelphia woman whose body has a waxlike texture), and a diseased colon measuring 2.7 meters (9 ft) with 18 kilograms (40 lb) of fecal matter.

It’s no surprise that visitors are often warned to avoid eating before their visit.

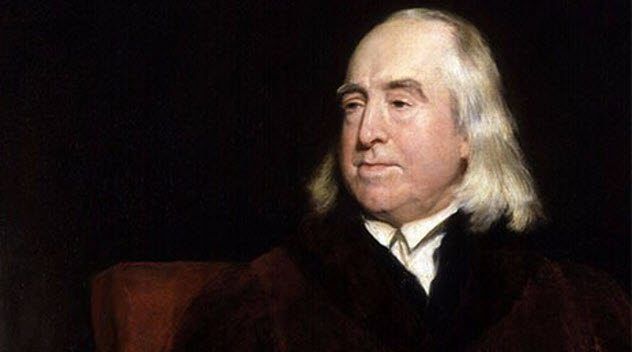

8. The Head of Jeremy Bentham

Jeremy Bentham, a philosopher known for his eccentricity, lived from 1748 to 1832. His peculiar nature was evident in naming his cat The Reverend Sir John Langbourne. Bentham also requested that his body be preserved posthumously so he could attend his friends’ gatherings.

Honoring Bentham’s wishes, his body was preserved and is now displayed at University College London. However, his actual head was detached and replaced with a wax replica. This separation wasn’t Bentham’s request but resulted from a botched embalming process.

Bentham had asked for his head to be preserved using the Maori method from New Zealand. Unfortunately, his friend Dr. Southwood Smith, who performed the embalming, was unfamiliar with the technique, leading to the head’s deterioration and eventual removal.

The original head was once exhibited but was moved to storage in the 1990s after being stolen by students from a competing university.

7. The Tooth and Fingers of Galileo Galilei

Renowned astronomer Galileo Galilei passed away in 1642. During the relocation of his body to a new tomb opposite Michelangelo’s in Florence, Italy, in 1737, admirers took the chance to remove three of his fingers, a tooth, and a vertebra.

One finger found its way to the Museum of the History of Science in Florence, while the thumb, middle finger, and tooth remained in the possession of a private family.

The family-held relics disappeared in the 20th century but resurfaced in 2009. To prevent further loss, the Museum of the History of Science acquired the fingers and tooth, displaying them alongside the third finger.

The museum, now known as the Galileo Museum, holds more of Galileo’s remains than any other institution. Meanwhile, his vertebra is preserved at the University of Padua.

6. The Head of Antonio Scarpa

Antonio Scarpa, an Italian anatomist and neurologist, passed away on October 31, 1832. During his tenure at the University of Pavia, he gained more enemies than allies due to his arrogance, rumor-mongering, and nepotism, favoring friends and illegitimate children for university positions.

Scarpa’s autopsy was performed by Carlo Beolchin, a former assistant, who removed Scarpa’s head, thumb, index finger, and urinary tract. The exact motive behind Beolchin’s actions remains unknown.

Some speculate that Beolchin preserved these body parts for posterity. However, given Scarpa’s harsh nature, it’s equally possible Beolchin removed them as an act of revenge. Scarpa’s rivals, unable to obtain his remains, vandalized a marble statue dedicated to him.

Scarpa’s body parts, except for his head, were stored in an Italian museum. His head was initially concealed but later resurfaced and was displayed at the Museo per la storia dell’Universita di Pavia. While the museum now holds his other remains, they have chosen to keep them in storage.

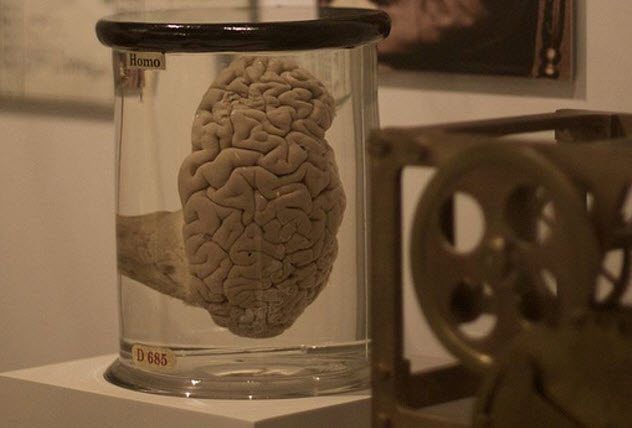

5. The Brain of Charles Babbage

Charles Babbage, the inventor of the modern computer and hailed as the “father of the computer,” has half of his brain displayed at the Science Museum in London and the other half at the Hunterian Museum within the Royal College of Surgeons. Unlike Einstein, Babbage explicitly desired his brain to be preserved outside his skull.

Prior to his passing in 1871, Charles penned a letter to his son Henry, outlining his desires regarding the fate of his brain. He expressed no reservations about its removal and preservation posthumously, as long as it served to further scientific endeavors.

Within the correspondence, Charles instructed Henry to handle his brain in whatever way he deemed most beneficial for the progression of human understanding and the betterment of mankind.

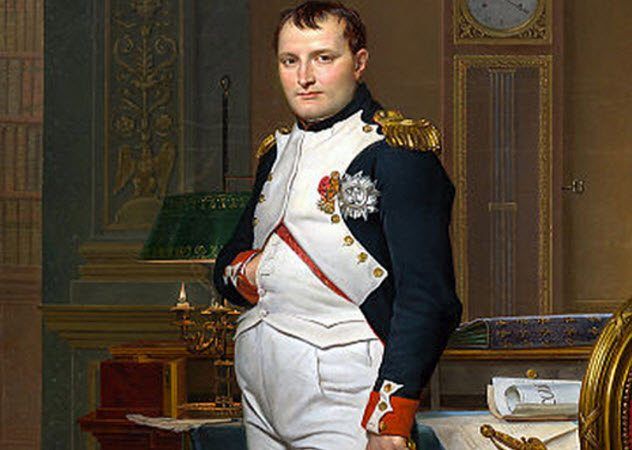

4. Napoleon Bonaparte’s Penis

The downfall of Napoleon Bonaparte commenced with his loss at the Battle of Waterloo. This defeat led to his abdication from the French throne, subsequent capture by British forces, and exile to St. Helena, where he met his demise under questionable conditions in 1821. Additionally, his penis was removed during an autopsy aimed at uncovering the cause of his death.

Dr. Francesco Autommarchi, the physician who conducted the autopsy, extracted Napoleon’s penis—reportedly measuring a mere 3.8 centimeters (1.5 inches)—in front of 17 witnesses. He then handed the diminutive organ to Abbe Anges Paul Vignali, the clergyman who administered Napoleon’s final sacraments.

In 1924, a bibliophile acquired the penis, which later changed hands to a buyer in Philadelphia. By 1927, it was exhibited at the Museum of French Art in New York.

A journalist from Time magazine, upon viewing the penis at the museum, described it as “a maltreated strip of buckskin shoelace.” The artifact was auctioned off to John J. Lattimer in 1977 and has since stayed within the Lattimer family’s possession.

3. Mata Hari’s Skull

Mata Hari is widely regarded as one of the most prominent spies of the 20th century, though her true allegiances remain a subject of intense debate. Speculations suggest she may have worked for France, Germany, or even both. Despite the uncertainty, she was executed by France on October 15, 1917, accused of espionage for Germany during World War I.

Some historians argue that France used Mata Hari as a convenient scapegoat to justify their wartime setbacks. Her profession as a high-profile courtesan with ties to influential German figures made her an ideal target for blame.

Following her execution, Mata Hari’s body remained unclaimed and was sent to a Paris medical school for anatomical research. Her skull was separated and preserved at the Museum of Anatomy, where it later vanished under mysterious circumstances.

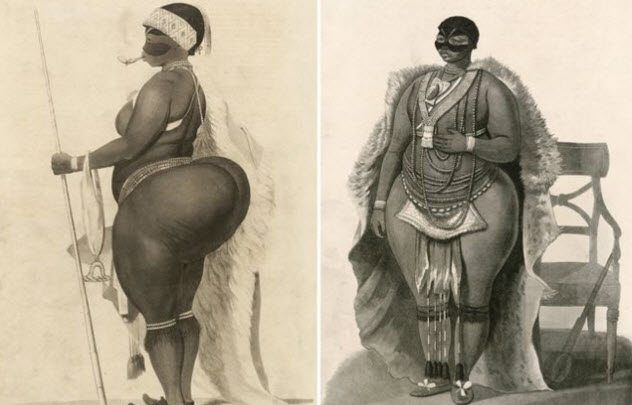

2. Sarah Baartman’s Brain And Genitals

Born in 1789 in Eastern Cape, South Africa, Sarah Baartman had a medical condition known as steatopygia, which led to an unusual accumulation of fat in her buttocks. This made her buttocks significantly larger than average, sparking widespread curiosity.

In October 1810, despite being unable to read or write, Baartman signed documents allowing surgeon William Dunlop and her employer, Hendrik Cesars, to transport her to England for public exhibition.

Baartman was showcased under the name “Hottentot Venus,” adorned in beads, feathers, and skin-tight outfits that matched her complexion, often seen smoking a pipe. She later moved to Paris in 1814, where she passed away the following year.

Following her death, naturalist Georges Cuvier conducted an autopsy. Her brain, skeleton, and genitals were displayed at the Paris Museum of Man until 1974. At the request of President Nelson Mandela in the 1990s, her remains were repatriated to South Africa in March 2002 and laid to rest in Hankey.

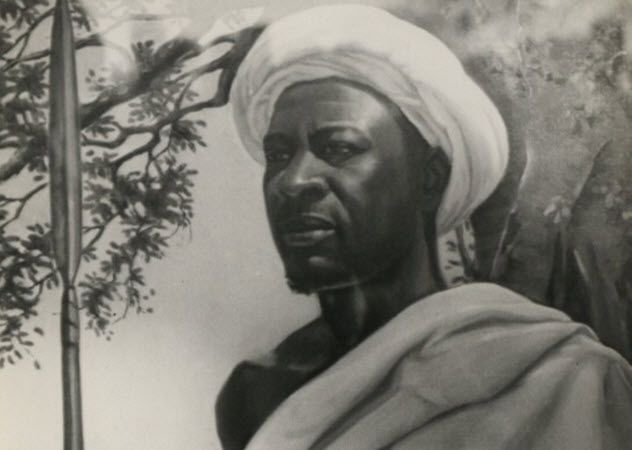

1. Chief Mkwawa’s Skull

Chief Mkwavinyika Munyigumba Mwamuyinga, also known as Chief Mkwawa, is celebrated for his relentless resistance against the German occupation and colonization of the Hehe tribal lands in present-day Tanzania. In 1891, he led a rebellion against German forces, even slaying a high-ranking German officer in combat. Despite the Germans capturing Hehe villages and forts, Chief Mkwawa evaded capture, employing guerrilla warfare tactics.

In 1898, surrounded by German troops, Chief Mkwawa took his own life by shooting himself in the head. However, the Germans were not content with his death alone. They decapitated him and sent his skull to Berlin.

During World War I, the Hehe allied with Britain against Germany. Following Britain’s victory, the Treaty of Versailles in 1919 included a clause mandating Germany to return Chief Mkwawa’s skull to the Hehe as a gesture of gratitude for their support.

Despite this, Germany failed to locate the skull, leaving the Hehe empty-handed. After World War II, Sir Edward Twining, the governor of Tanganyika, renewed efforts to recover the skull. His search led him to the Bremen Museum in Germany, where he discovered 2,000 skulls, including 84 from Tanzania.

Among the skulls, only one bore a bullet hole in the head, leading Twining to conclude it was Chief Mkwawa’s. Today, the skull is showcased at the Mkwawa Memorial Museum in Kalenga, Tanzania.