Across the world, numerous abandoned towns pose serious risks to any visitors. Many of these eerie locations were left behind after devastating environmental damage, leaving the former residents with severe health issues. The aftermath of these toxic environments endures for years, and even today, these ghost towns continue to present dangers to curious tourists.

10. Picher, Oklahoma

Picher emerged in 1914 when lead and zinc deposits were discovered in the area. The town quickly flourished as both metals were in high demand during World War I. The hardworking miners from Picher contributed greatly to the war effort, with over half of the lead and zinc used during that time coming from local mines. Ultimately, Picher became one of the world’s top exporters of these valuable metals.

Sadly, the mining process left behind a dangerous byproduct known as chat—a toxic, powdery white substance. When the mining operations ceased in the 1970s, approximately 178 million tons of chat, mill sand, and sludge were scattered around the town, creating an ongoing environmental hazard.

The townspeople were unaware of the highly toxic nature of chat. They used it to pave their driveways and fill their children’s sandboxes. Families would picnic on the chat piles, children rode their bikes over them, and the high school track team trained on the hazardous surface.

In the 1990s, a school counselor discovered a connection between lead exposure and learning disabilities. After testing the children, it was found that 46 percent of the students had dangerously high levels of lead in their blood. The government initiated efforts to clean up the town but abandoned the project when sinkholes started to appear, endangering the structures. Faced with the threat of collapsing buildings, authorities decided to relocate the town's residents, offering them a buyout. Almost all of them left, though a few chose to stay behind.

Picher remains toxic. While air quality standards meet the government's minimum requirements, strong winds still carry dangerous amounts of lead throughout the town. Even wildlife is not immune to the area's toxins. In 2015, over 1,000 migratory birds were found dead across Picher, believed to have succumbed to zinc poisoning.

9. Bikini Atoll, Republic of the Marshall Islands

In 1946, a U.S. Navy official visited the people of Bikini Atoll, telling them they were like the Israelites—a chosen people—and that their land was needed to perfect the atomic bomb in order to prevent future conflicts. The Bikini Islanders agreed to temporarily leave their island for this cause.

For the next eight years, the U.S. government conducted nuclear detonations on the Marshall Islands, dropping 67 bombs in total. Of those, 23 bombs fell on Bikini Atoll alone, including one bomb that was a thousand times more powerful than the one that destroyed Hiroshima.

By the late 1960s, U.S. officials claimed that most of the nuclear fallout from the detonations had dissipated. Many Bikini Islanders chose to return home, but after ten years, they began experiencing the devastating side effects of radiation exposure. Women faced numerous miscarriages and stillbirths, while surviving children often suffered from birth defects. The population also saw a surge in thyroid problems and cancer rates far higher than in other countries.

Scientists discovered dangerously high levels of radiation on Bikini Atoll, forcing the island's residents to evacuate once more. The island remains uninhabitable today, with radiation levels nearly double the safe limit for human habitation.

8. Geamana, Romania

In 1977, Nicolae Ceaușescu, the dictator of Romania, decided to exploit a massive copper deposit. The toxic waste from the mine needed disposal, and Ceaușescu chose to drown the village of Geamana. Four hundred families were forcibly relocated as much of the village was submerged under a man-made lake designed to collect the contaminated sludge from the mine.

At its peak, the copper pit produced approximately 11,000 tons of copper annually. As mining operations expanded, so did the artificial lake that had formed. Today, only a church and a few houses remain of the once-thriving town, and the lake continues to rise by one meter each year. Eventually, the entire town will be submerged under toxic sludge.

The lake is highly toxic, containing a variety of harmful chemicals that have turned parts of the water bright red. It has ten times the normal concentration of cadmium, a deadly metal. Prolonged exposure to cadmium can cause mutations in plants and animals, as well as severe damage to human liver, kidney, and lung function.

7. New Idria, California

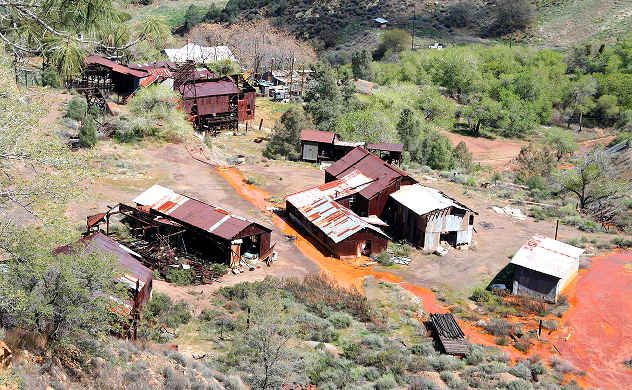

New Idria was established in 1854 near one of the largest and most productive mercury mines in the United States. The mine’s value was so high that armed guards were assigned to protect it during World War I. Mining operations continued until 1971 when the company shut it down, and the town was abandoned shortly thereafter.

No cleanup efforts were made at the site. Over 30 miles of underground tunnels leak mercury-laden water, contaminating the local river, which has turned a vivid orange. The water is tainted with mercury, aluminum, iron, and nickel, and is as corrosive as battery acid.

The contaminated water flows into nearby streams, affecting the local wildlife. Bacteria transform mercury into methylmercury, a major hazardous waste threat in the country. Methylmercury accumulates in fish, and consuming the tainted fish can lead to symptoms such as headaches, tingling, and tremors. In severe cases, particularly among children, it can cause permanent damage to the brain and nervous system.

6. Wittenoom, Western Australia

Wittenoom was home to Australia's sole blue asbestos mine, which operated from the 1940s for over 30 years. Once the harmful connection between asbestos dust and lung disease became clear, the Australian government closed the mine.

By that time, however, the asbestos had already taken its toll on the town and its residents. Of the 20,000 individuals who lived and worked in Wittenoom during the mining years, at least 2,000 have died from diseases related to asbestos exposure. Even those who never worked in the mines were affected. Children who grew up in Wittenoom face a 20–83 percent higher risk of dying from cancer compared to the general population.

The government briefly considered cleaning up Wittenoom but ultimately decided it would be cheaper and safer to relocate its residents and abandon the town. Throughout Wittenoom, vast piles of tailings—fine, toxic residue left after asbestos processing—still remain.

The asbestos threat in Wittenoom goes beyond the mounds of tailings. For decades, the local government used asbestos waste as construction material. It was mixed into roads, pipelines, the airstrip, and even golf courses. Residents also brought it into their homes, using it for sandpits and to control dust around their properties.

The entire landscape of Wittenoom is saturated with microscopic asbestos fibers. When inhaled, these tiny particles can penetrate the lungs, causing inflammation and releasing harmful mutagens that trigger tumor growth. Even short-term exposure to asbestos can lead to deadly diseases like mesothelioma and lung cancer.

5. Pripyat, Ukraine

Pripyat was established just two miles from the Chernobyl Nuclear Power Plant. Built as a model city by some of the finest architects, Pripyat was meant to embody a utopian vision of communism, with a perfect harmony between work and social life.

In 1986, a catastrophic safety test failure led to explosions at Chernobyl, releasing thousands of tons of radioactive waste into the atmosphere. The radiation cloud was so powerful that it caused nearby forests to die, a clear sign of the toxic fallout that spread throughout the region.

The Soviet government delayed evacuating Pripyat for 36 hours, by which time many residents were already exhibiting signs of radiation sickness. Thirty-one people died within a month of the Chernobyl disaster. The World Health Organization’s cancer research estimates that at least 9,000 people will die from radiation exposure. Greenpeace, however, predicts the death toll could ultimately reach as high as 90,000 in the long run.

Pripyat's radiation levels have decreased over time. Today, much of the city is less radioactive than the amount of exposure one would receive from passing through an airport security scanner three times. A brief visit poses little risk, but living near the city remains dangerous. Studies of local wildlife reveal the long-lasting effects of radiation, with smaller brains in birds, slower-growing trees, and a dramatic decline in insect populations.

4. Treece, Kansas

Treece, Kansas emerged in the early 20th century after the discovery of lead, zinc, and iron ore deposits. Alongside nearby Picher, Treece was a key supplier of ore during the World Wars. However, mining ceased in the 1970s, and by then, the town's environment had already been severely damaged.

The air in Treece is dangerously polluted. The town is surrounded by millions of tons of waste from lead and zinc mining. Huge piles of chat, a byproduct of mining, encircle the town, and the wind sweeps the toxic dust throughout the area.

The ground itself is perilous. Decades of mining have rendered the earth unstable, with numerous cave-ins over time. The oldest sinkholes, once used by children as swimming spots, are now filled with toxic water. After playing in them, the children returned home with irritated skin, which their parents thought was sunburn. However, they had suffered chemical burns instead.

The residents of Treece began to suspect that lead poisoning was affecting them, and blood tests confirmed their suspicions. The town was deemed uninhabitable, and the government offered buyouts, which most people accepted. Cleanup is still ongoing, but no new buildings will ever be allowed in Treece due to the contamination.

3. Centralia, Pennsylvania

In 1962, authorities decided to burn a large pile of trash at Centralia's dump. Unfortunately, much of the dump—and the town itself—was situated on top of an old coal mine. After the fire consumed the trash, it ignited the remaining coal.

The fire spread through the mines, causing carbon monoxide to leak up from the ground, making residents lose consciousness in their homes. Sinkholes and cracks began to appear throughout the town. After a 12-year-old boy fell into a burning sinkhole in the 1980s and survived, the government ramped up efforts to extinguish the fire. Despite their best efforts, the fire could not be stopped, leading to the relocation of the entire town's population.

Today, the town is nearly deserted, and the fire continues to burn. It has ravaged much of the mine, consuming its timber and bracing. The remaining mine structure is on the brink of collapse, making the ground above hazardous. Centralia’s air is equally deadly, with sulfurous steam rising from numerous cracks in the ground. The poisonous gases can suffocate anyone nearby.

2. Kantubek, Uzbekistan

Kantubek, a remote town on Vozrozhdeniye Island, was once the site of Soviet bioweapons testing. The Soviet Union’s scientists experimented with weaponizing diseases and tested them on animals brought from the town. These animals were exposed to various pathogens before being returned to the lab for further analysis.

Despite their efforts to contain the diseases, including spraying poison over the test areas, some rodents likely survived by burrowing underground. These animals might have been exposed to weapons-grade bubonic plague bacteria, which fleas transmitted across generations. This antibiotic-resistant strain of plague would prove fatal to humans.

Bubonic plague isn't the only dangerous substance still lurking on the former island. Vozrozhdeniye also housed a stockpile of anthrax. While the United States destroyed much of the anthrax spores buried on the island, their quick cleanup operation may have missed some. Anthrax spores can survive for decades underground.

1. Bento Rodrigues, Brazil

Bento Rodrigues was situated near an iron ore mine, with the mine’s waste being dumped into a nearby lake. A dam was meant to protect the village from the toxic water. However, in 2015, the dam’s containment wall gave way, unleashing 35 million liters (9.2 million gallons) of poisonous clay.

A massive 32-foot-high (10 m) wave of sludge surged through Bento Rodrigues, drowning the town in red-colored mud. United Nations environmental experts visited the site and discovered that the mud contained dangerously high levels of toxic metals and other harmful chemicals. The experts also found that the town’s water was tainted with arsenic and lead at levels 10 to 20 times higher than Brazil's legal limit.

The owners of the mine were forced to relocate the residents of Bento Rodrigues. The town may never be safe for its original inhabitants to return. It will take anywhere from 10 to 50 years for the region’s environment to recover, if it ever does. There’s a real possibility that the area may never be livable again.