Before you lament your mundane office job, consider the Victorian era—a time devoid of workplace safety regulations—and feel fortunate. In those days, people resorted to unconventional and often hazardous methods to make ends meet, from scavenging sewers for valuables to trading in waste products.

1. The Leech Gatherer

Leeches were highly sought after, used by both legitimate physicians and charlatans to treat various conditions, from migraines to so-called "hysteria." However, the task of gathering these creatures was far from glamorous. Often, impoverished rural women would venture into murky waters, using their own bodies as bait to lure leeches. Once the parasites latched onto their skin, the collectors would carefully remove them and store them in containers. Remarkably, leeches could survive without food for nearly a year, making them easy to stockpile in apothecaries for future use. Sadly, those who collected leeches faced significant risks, including severe blood loss and exposure to deadly infections.

2. Pure Finder

Despite its deceptively pleasant name, this occupation involved gathering dog excrement from London's streets to sell to tanners, who utilized it in leather production. Referred to as "pure," the waste was valued for its ability to treat and soften leather [PDF]. Leather was highly sought after during the Victorian era, serving purposes ranging from equestrian gear to footwear, bags, and bookbinding. Pure finders frequented areas teeming with stray dogs, collecting the waste in covered buckets for sale to tanners. While some wore a black glove to shield their hands, others believed bare hands were easier to clean and opted against protection.

3. Tosher

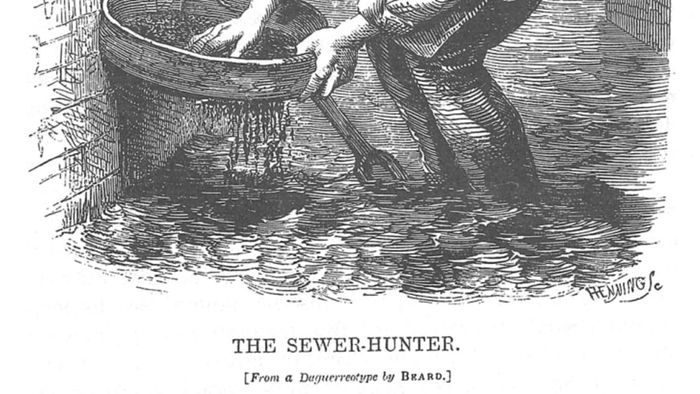

An 1851 depiction of a sewer-hunter, also known as a "tosher." | Wikimedia // Public Domain

An 1851 depiction of a sewer-hunter, also known as a "tosher." | Wikimedia // Public DomainVictorian London's extensive sewer system, overwhelmed by the waste of its dense population, became the workplace for toshers. These individuals ventured into the dark, hazardous tunnels to search through raw sewage for valuable items lost down drains. The job was perilous: toxic gases, collapsing tunnels, rat infestations, and sudden floods posed constant threats. To mitigate these dangers, toshers worked in teams, identifiable by their canvas trousers, multi-pocketed aprons, and chest-mounted lanterns. Many also carried long poles with hoes to sift through waste or steady themselves in the murky environment. After 1840, sewer entry without permission was outlawed, prompting toshers to operate during late-night or early-morning hours to evade authorities. Despite the foul and risky conditions, the trade was profitable, with coins and silverware often found amidst the filth.

4. Matchstick Makers

Matchstick production involved cutting wood into thin sticks and coating their ends with white phosphorus, a highly poisonous substance. During the Victorian era, this task was predominantly carried out by teenage girls laboring in appalling conditions. They worked 12 to 16 hours daily with minimal breaks and ate at their stations, leading to phosphorus contamination in their food. This exposure caused some to develop “phossy jaw,” a horrific condition where the jawbone became infected and severely disfigured.

5. Mudlark

Similar to toshers, mudlarks eked out a living by scavenging through muck for sellable items, though they worked along the Thames' shores rather than in sewers. Considered a lower-tier occupation, mudlarks were typically children who collected rags for papermaking, driftwood for firewood, and any coins or valuables washed into the river. The job was not only filthy but also hazardous, as the Thames' tides could easily sweep children away or trap them in the soft mud.

6. Chimney Sweep

A chimney sweeper in Ireland, 1850. | Wikimedia Commons // Public Domain

A chimney sweeper in Ireland, 1850. | Wikimedia Commons // Public DomainChildren as young as four were employed as chimney sweeps, their small size making them ideal for navigating narrow chimneys. The cramped, sooty environment caused raw scrapes on their elbows and knees, which eventually hardened into calluses. Constant exposure to soot and smoke led to severe lung damage for many. To keep them small, some sweeps were deliberately underfed, ensuring they remained in demand. Most outgrew the job by age 10. Tragically, some children got stuck in chimneys or refused to climb, and stories suggest bosses would light fires below to force them upward. An 1840 law banned anyone under 21 from chimney sweeping, though some ignored the regulation.

7. Funeral Mute

Readers of Charles Dickens’s Oliver Twist will recall the protagonist’s despised role as a mute for undertaker Mr. Sowerberry. A key part of Victorian funeral customs, mutes wore all-black attire with a sash (typically black, but white for children), carried a draped staff, and stood solemnly at the deceased’s home before guiding the coffin to the burial site.

8. Rat Catcher

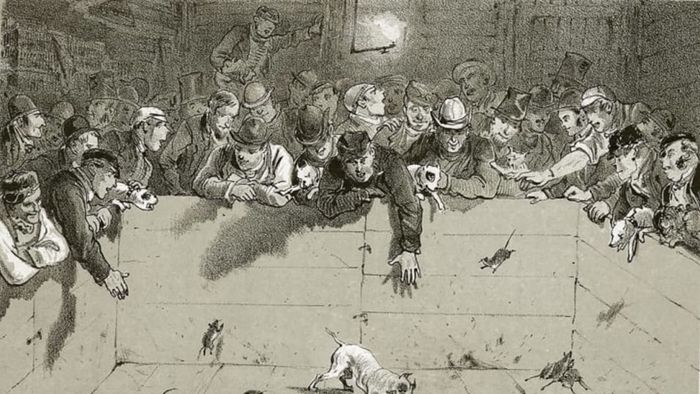

This was no occupation for those with a fear of rodents. | Rischgitz /Getty Images

This was no occupation for those with a fear of rodents. | Rischgitz /Getty ImagesRat catchers often used dogs or ferrets to hunt down rats plaguing Victorian streets and homes. They typically captured the rats alive, selling them to “ratters” who staged pit fights between the rodents and terriers for betting spectators. The job was perilous, as rats carried diseases and their bites could cause severe infections. Jack Black, a renowned Victorian rat catcher employed by Queen Victoria, was featured in Henry Mayhew’s London Labour and the London Poor (1851). Black used a cage capable of holding up to 1000 live rats, feeding them to prevent cannibalism and preserve his stock.

9. Crossing Sweeper

The role of a crossing sweeper highlights the resourcefulness of the Victorian poor. Children would stake out a section of the street, and when affluent individuals stepped out of their carriages, the sweepers would clear debris from their path to keep their clothes and shoes clean. Crossing sweepers were seen as slightly above beggars, relying on tips for their efforts. Their work was often valued, as streets were filthy with mud and horse manure. These young workers braved harsh weather and the constant danger of speeding carriages and buses.

10. Resurrectionists

This is one profession best left in the past. | Hulton Archive/Getty Images

This is one profession best left in the past. | Hulton Archive/Getty ImagesIn the early 1800s, medical schools and anatomists faced a dire shortage of cadavers, as only executed criminals' bodies were legally available for dissection. This scarcity led to high payments for well-preserved corpses, prompting opportunistic Victorians to exhume freshly buried bodies. The issue grew so rampant that grieving families often stood watch over graves to stop resurrectionists from stealing their loved ones.

The practice reached a horrifying peak with William Burke and William Hare, who allegedly killed 16 people between 1827 and 1828. The duo lured victims to their boarding house, intoxicated them, and suffocated them to preserve the bodies for sale to Edinburgh University’s medical school. Their crimes prompted the Anatomy Act of 1832, which expanded legal access to cadavers and allowed individuals to donate their bodies to science, effectively ending the gruesome resurrectionist trade.