This ranking evaluates the impact, depth of understanding, and broad intellectual curiosity of various 'lovers of wisdom,' organizing them based on their contributions. It’s essential to recognize that philosophy, in its classical form, was synonymous with science. Thinkers like Aristotle employed reason to gain scientific understanding of the world. The distinction between philosophy and the physical sciences emerged only in more recent times.

10. John Locke

The most pivotal figure in modern political thought, John Locke, is largely credited with inspiring Thomas Jefferson’s language in “The Declaration of Independence” and the U.S. Constitution. Known as the “Father of Liberalism,” Locke advanced the principles of humanism and individual freedom, building on ideas introduced by #1. Liberalism, the belief in equal rights under the law, is often traced back to Locke. He famously coined the phrase “government with the consent of the governed” and identified three inherent natural rights: “life, liberty, and estate.”

He opposed the European tradition of nobility, which allowed some to inherit land based on lineage while the poor remained impoverished. Locke, primarily through Jefferson, is credited with eliminating the concept of nobility in America. While nobility and hereditary privileges persist in Europe, particularly among the remaining monarchies, the practice has nearly disappeared. The modern democratic ideal only emerged after Locke’s liberal theories gained traction.

Explore a fresh perspective on philosophy with The Worldly Philosophers: The Lives, Times And Ideas Of The Great Economic Thinkers available at Amazon.com!

9. Epicurus

Epicurus has been unfairly labeled over the centuries as a proponent of indulgence and excessive pleasure. He faced strong criticism from Christian polemicists, particularly during the Middle Ages, as he was perceived as an atheist. His philosophy for a fulfilling life was encapsulated in his famous principles: “Don’t fear god; don’t worry about death; what is good is easy to obtain; what is terrible is easy to endure.”

He promoted the idea of rejecting belief in anything intangible, including deities, viewing such concepts as preconceived notions that could be easily manipulated. Epicureanism can be summarized as “no matter what happens, enjoy life because it’s fleeting and singular.” Epicurus believed happiness stemmed from treating others fairly, avoiding pain, and living in a way that brings personal satisfaction without excess.

He also supported a version of the Golden Rule: “A pleasant life is unattainable without wisdom, virtue, and justice (agreeing ‘neither to harm nor be harmed’), and wisdom, virtue, and justice are unattainable without a pleasant life.” For Epicurus, “wisely” meant avoiding pain, danger, and disease; “well” involved maintaining a healthy diet and exercise; and “justly” meant adhering to the Golden Rule by not harming others, as you wouldn’t want to be harmed.

8. Zeno of Citium

Though less widely known than others on this list, Zeno established the Stoic school of thought. Stoicism derives from the Greek “stoa,” referring to a covered walkway, particularly the Poikile, a colonnaded area in Athens’ marketplace during the 3rd Century BC. Stoicism teaches that suffering arises from errors in judgment and that we must maintain absolute control over our emotions. Emotions like anger, joy, and sadness are seen as flaws in reasoning, implying we are emotionally vulnerable only when we allow ourselves to be. In essence, the world is shaped by our perception.

Epicureanism is often seen as the antithesis of Stoicism, though many today confuse or blend the two. Epicureanism posits that life contains displeasures which must be avoided to achieve perfect mental tranquility (ataraxia in Greek). Stoicism, on the other hand, teaches that mental peace comes from the deliberate choice not to let external events disturb you. Death is inevitable, so why feel sorrow when it occurs? Sadness is unproductive and only causes harm. Similarly, anger serves no purpose and leads to no good. By mastering one’s emotions, one can attain inner calm. Crucially, desires should be avoided: strive only for what is necessary, as excess leads to harm, not fulfillment.

7. Avicenna

His full name, Abū ʿAlī al-Ḥusayn ibn ʿAbd Allāh ibn Sīnā, was Latinized into the more familiar form in Western history. He lived in the Persian Empire from around 980 to 1037. Contrary to popular belief, the Dark Ages were not entirely devoid of progress. Beyond his philosophical contributions, he was also the foremost physician of his time. His most renowned works include The Book of Healing (which focuses on philosophy, not medicine) and The Canon of Medicine, a comprehensive compilation of medical knowledge available during his era.

Influenced primarily by #1, his Book of Healing covers topics ranging from logic and mathematics to music and science. He correctly theorized that Venus is closer to Earth than the Sun, a fact not obvious at the time. He dismissed astrology as unscientific, arguing it relied on conjecture rather than evidence. He also proposed that a mineral-rich fluid deep underground was responsible for fossilizing bones and wood, suggesting that “a powerful petrifying force, emerging from certain rocky areas or during earthquakes and ground shifts, transforms whatever it touches. The fossilization of plants and animals is no more extraordinary than the transformation of water.”

While not entirely accurate, this idea is closer to the truth than one might assume. Petrifaction can affect any organic material, particularly wood, which becomes infused with silica deposits, transforming it from its original state into stone. Avicenna was the first to identify the five classical senses: taste, touch, sight, hearing, and smell. He may also have been the world’s first systematic psychologist, challenging the belief that mental disorders were caused by demonic possession. Avicenna proposed that recovery was possible through somatic means, involving the body and brain.

John Stuart Mill’s five methods of inductive logic largely derive from Avicenna, who initially outlined three of them: agreement, difference, and concomitant variation. While explaining them in detail here would be lengthy, these methods are forms of syllogisms, fundamental to philosophical education. They are essential to the scientific method, and anyone constructing a syllogism is employing at least one of these approaches.

6. Thomas Aquinas

Aquinas is best known for his argument proving the existence of God, asserting that the Universe must have been created by something, as everything in existence has a beginning and an end. This is now called the “First Cause” argument, a theory philosophers have debated ever since. Aquinas based his argument on the concept of “ού κινούμενον κινεῖ,” from #1, which translates to “the unmoved mover” or “one who moves while not moving.”

Aquinas grounded all his theories in Christian doctrine, which limits his universal appeal today. Even Christians argue that since his ethical teachings were derived solely from the Bible, they lack independent authority. However, his goal was to make ethics accessible to ordinary people without delving into abstract philosophy. He expanded on #2’s principles, now known as the “cardinal virtues”: justice, courage, prudence, and temperance. This straightforward, four-part framework allowed him to connect with the masses effectively.

He presented five renowned arguments for God’s existence, which remain fiercely debated by both theists and atheists. Among these, one is called “the unity of God,” asserting that God is indivisible. He possesses both essence and existence, inseparable qualities. Thus, if we can describe something with inseparable attributes, it proves God’s existence. Aquinas used the statement “God exists” as an example, where the subject and predicate are identical.

5. Confucius

Master Kong Qiu, as he is known in Chinese, lived from 551 to 479 BC and remains the most influential philosopher in Eastern history. He advocated ethical and political principles during the same era the Greeks were exploring similar ideas. While democracy is often credited to the Greeks, Confucius wrote in his Analects that “the best government governs through ‘rites’ and the people’s inherent morality, rather than coercion or bribery.” Though this seems obvious today, he articulated it in the 5th to 4th centuries BC. This aligns with the Greek concept of democracy, emphasizing governance by the people’s moral authority.

Confucius supported the concept of an Emperor but emphasized the need to limit the emperor’s authority. The emperor must act with integrity, earning the respect of his subjects. If he errs, his subjects should offer corrective advice, which he must consider. Any ruler who violates these principles is deemed a tyrant, more of a thief than a legitimate leader.

Confucius also formulated his own version of the Golden Rule, which had existed in Greece for at least a century before him. His wording was nearly identical but expanded the idea: “Do not impose on others what you do not desire for yourself; grant others what you recognize as desirable for yourself.” The first part is a passive call to avoid harm, while the second is an active call to help others. The only other ancient philosopher to advocate the Golden Rule in its positive form was Jesus of Nazareth.

Smart is the new sexy! Flaunt your intellect with this stylish I Heart Confucius T-Shirt available at Amazon.com!

4. Rene Descartes

Descartes, who lived from 1596 to 1650, is often called the “Father of Modern Philosophy.” He developed analytical geometry, founded on the Cartesian coordinate system, which remains a cornerstone of mathematics education and application. Analytical geometry involves studying geometry through algebra and the Cartesian system. He also uncovered the laws of refraction and reflection and introduced superscript notation for exponents, still in use today.

He championed dualism, emphasizing the mind’s dominance over the body: true strength comes from disregarding physical limitations and harnessing the mind’s boundless potential. Descartes’ most famous declaration, now synonymous with existentialism, is: “Je pense donc je suis;” “Cogito, ergo sum;” or “I think, therefore I am.” This statement isn’t about proving bodily existence but rather affirming the mind’s existence. He dismissed perception as unreliable, advocating deduction as the sole trustworthy method for analysis and proof.

He also supported the Ontological Argument for the Existence of a Christian God, asserting that God’s benevolence allows him to trust his senses, as God has equipped him with a functioning mind and sensory system and does not intend to deceive him. From this, Descartes concluded that knowledge of the world can be acquired through deduction and perception. In epistemology, he contributed foundationalism (the concept of basic beliefs) and the idea that reason is the only reliable path to knowledge.

3. Aristotle

Aristotle, who also leads another of this lister’s philosophy rankings, unsurprisingly holds a high position here. He was the first to develop systematic methods for analyzing and critiquing diverse fields, from logic and ethics to politics, literature, and science. He proposed that everything in existence has four “causes”: the material cause (what something is made of), the formal cause (its structure), the efficient cause (its creator), and the final cause (its purpose).

While this may seem obvious, delving into classical causality in detail would exceed the scope of a top ten list. However, it’s worth noting that every philosopher since Aristotle has engaged with his ideas, either building on or challenging them. His framework remains foundational; discussing causality inevitably involves referencing or refuting Aristotle’s theories.

Aristotle also introduced the concept of a universal hierarchy of life, arguing that nature operates with purpose. He observed that certain animals dominate others, and plants and animals interact in a structured way. His “ladder of life” consists of eleven levels, with humans at the top. Medieval Christian thinkers expanded this idea, applying it to the hierarchy of God, humans, and angels. Thus, the angelic hierarchy in Catholicism, often seen as uniquely Catholic, actually originates from Aristotle, who lived centuries before Jesus. Aristotle’s ideas were central to classical education throughout the Medieval period.

Aristotle contributed to nearly every subject, whether abstract or concrete, and modern philosophy often builds on his principles, ideas, or discoveries. His ethical teachings emphasized action over mere intention: a person’s kindness, mercy, or charity only holds value when demonstrated through helping others. While much more could be said about Aristotle, this list must conclude. Many other thinkers deserve honorable mentions, so feel free to add them as you see fit.

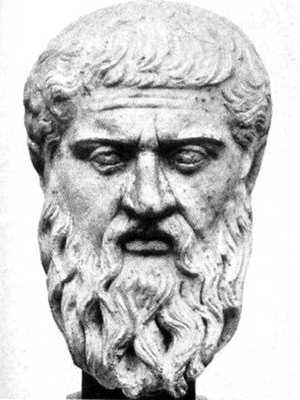

2. Plato

Plato, who lived from approximately 428 to 348 BC, established the Western world’s first institution of higher learning, the Academy of Athens. Nearly all Western philosophy can be traced back to Plato, who was a student of Socrates and preserved many of his teacher’s ideas through his writings. If Socrates ever wrote anything, it has not survived directly. Plato, along with another student, Xenophon, and the playwright Aristophanes, recorded much of Socrates’ teachings.

One of Plato’s most renowned quotes addresses politics: “Until philosophers become kings or kings genuinely embrace philosophy, and political power and philosophy merge, cities will never escape evil, nor will humanity.” He believed that rulers must possess wisdom; without it, they are ineffective. Only through philosophy can the world be freed from suffering. Plato favored a government led by benevolent aristocrats—educated, noble individuals who improve the lives of the common people. He opposed democracy, partly because he believed it led to the execution of his mentor, Socrates.

Plato’s most lasting contribution is his theory of “The Forms.” He discussed these forms extensively in his works, arguing that immaterial abstractions represent the highest form of reality. The material world is mutable, and our perceptions of it make its reality less concrete than that of immaterial abstractions. Plato believed that a creator must have shaped the Universe, and everything within it—our bodies and the physical world—is less real than this creator and the Universe itself. This idea laid the groundwork for #4’s existentialist philosophy.

1. Augustine of Hippo

Aurelius Augustinus (St. Augustine) lived in the Roman Empire from AD 354 to 430. After converting to Christianity in 386, he transitioned from teaching rhetoric to becoming the Bishop of Hippo. His works, including Confessions, The City of God, and Enchiridion, are cornerstones of Western thought. Augustine’s contributions to metaphysics, ethics, and politics remain influential, particularly his exploration of time, the nature of evil, and the criteria for just war.

Augustine’s most significant contribution lies in his interpretation of Christianity. In AD 400, Christianity was still in its early stages, lacking doctrinal unity. Augustine integrated Platonic and Neoplatonic philosophy into Christian theology, presenting God as an immaterial, transcendent reality. This concept of God, now widely accepted, was revolutionary at the time, as Augustine adapted Plato’s dualistic view of reality to describe a God existing beyond space and time—eternal and infinite.

While others, including Christians, had previously hinted at such metaphysical ideas, Augustine provided a structured, intellectual framework to support them. He emphasized that faith required more than blind belief; it demanded questioning and understanding. For Augustine, belief and comprehension were deeply interconnected, forming the foundation of genuine faith in religion.