Ancient surfaces vary from weathered clay to luxurious metals and vibrant dyes. These surfaces, whether part of awe-inspiring artifacts or simple pottery, often hold untold stories as significant as the objects themselves.

What lies hidden in the cracks can often reveal elusive truths or deepen the mystery. Myths may find scientific backing, or old beliefs may be disproven. Intriguingly, sometimes the unexpected emerges—the unique touch of an ancient artist or the surprising, sometimes odd, materials used in dye production.

10. The Smiley Pot

It's rare to find an ancient potter with a sense of humor. A 4,000-year-old pot has archaeologists grinning due to an unexpected discovery on its surface.

When it was uncovered in 2017 near the Syrian border in Turkey, everything seemed typical. Another broken vessel from a site that had been excavated for seven years and yielded many artifacts. However, the restoration team, as they reconstructed the pot, noticed something very familiar to modern eyes.

A smiley face.

Around 1700 BC, someone carved a pair of eyes into the soft clay and completed the design with a smile. The white pot with a single handle was used for drinking sherbet, a sweet beverage. While its function is clear, the reason for the artist’s addition of a joyful expression remains a mystery.

Regardless, the smiley face is now recognized as the oldest known smile in history. The site of Karkamis was once home to the Hittites, a Canaanite civilization, and the location of the historic Battle of Carchemish in 605 BC, which is mentioned in Jeremiah 46:2.

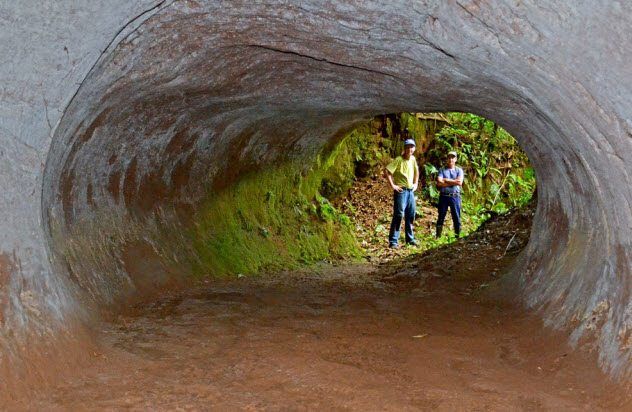

9. Paleoburrows

In the 2000s, Brazilian geologists began uncovering bizarre caves. Most featured flat floors and long, arched tunnels that snaked into intricate underground networks with exits, chambers, and passageways. They didn't appear to be the result of any natural geological processes.

Clues found on the ceilings and walls revealed the answer. Large grooves crisscrossed the surfaces, and further investigation confirmed they were ancient claw marks.

What makes these paleoburrows so perplexing is their scale. They are enormous, even for the giant sloths or armadillos thought to be their creators. The largest burrow, found in Rondonia in the Amazon, stretched 610 meters (2,000 feet) in total passage length. The main tunnels were originally 1.8 meters (6 feet) high and up to 1.5 meters (5 feet) wide.

Throughout its construction, which spanned multiple generations of workers, the creatures excavated 4,000 metric tons from the hill. There is no clear explanation for why these animals required such elaborate shelters, nor why no similar structures have been found in North America, where giant sloths and armadillos also roamed millennia ago.

8. Long-Distance Grave Tar

A unique type of ship was discovered near River Deben in England. Though it showed signs of wear from active service, the 27-meter (90 ft) vessel had been repurposed as a tomb. This find occurred eight decades ago at Sutton Hoo, an ancient burial site considered one of Britain’s most significant archaeological locations.

The ship, filled with precious metals and jewels, is believed to be the final resting place of King Raedwald, who passed away in AD 624 or 625. However, the most intriguing aspect was the presence of a black substance throughout the ship. Initially, it was thought to be Stockholm Tar, a material used for waterproofing.

In 2016, with the aid of advanced technology, tests revealed an unexpected outcome. The tar-like substance was identified as a rare form of bitumen native to the Middle East. The exact reason for the presence of this petroleum-based asphalt on the ship remains unclear.

Nevertheless, the sought-after material fit in with other prized grave goods. Some of these items were also imported, including from Egypt and the Eastern Mediterranean. The Sutton Hoo artifacts showed impressions, suggesting they were once attached to materials like leather or wood that have since decayed. The concentric marks indicated rotation, likely from either the object they were once attached to or the bitumen being employed as a tool.

7. A Coffin Artist’s Fingerprints

In 2005, a restoration team worked on an Egyptian coffin at the Cambridge Fitzwilliam Museum. The coffin, belonging to a priest named Nespawershefyt, who passed away around 1000 BC, revealed a surprising discovery. Beneath the lid, someone noticed the fingerprints of a fellow craftsman—a coffin artisan.

These marks were not left by a colleague's dirty hands but by the craftsmen who completed the coffin 3,000 years ago. For some reason, the ancient workers touched the inner lid before the varnish had fully dried. Their impatience resulted in leaving behind a couple of fingerprints for future generations to discover.

The researchers were thrilled by this personal touch. Another intriguing detail about the carpenters emerged after the coffin underwent a CT scan at Addenbrooke’s Hospital. It revealed that they had made significant adjustments to the original shape of the coffin.

The fingerprints were revealed to the public 11 years later in 2016, when they were featured in the first major exhibition dedicated to Egyptian artists and how their artistic styles evolved over a span of 4,000 years.

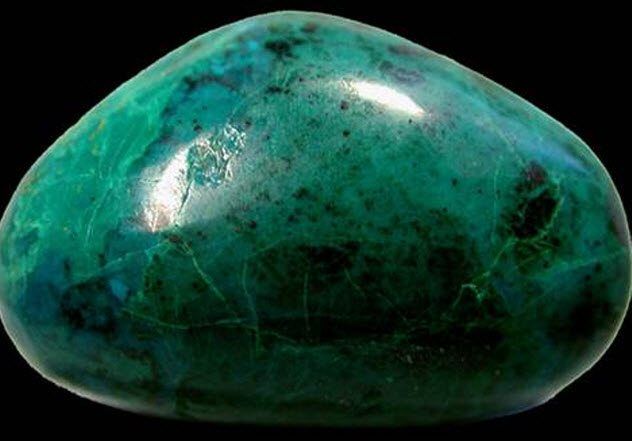

6. Green Magic For Children

The ancient Egyptians took colors seriously, attributing meaning and qualities to each one. Researchers know that green symbolized growth, crops, and health. It was so important that it was included in a scarab carving placed near a mummy's heart.

However, no one had any idea why green also had such significance when it came to Egyptian children. Ancient records and hieroglyphics reveal that young ones even wore green makeup.

A recent discovery has suggested that Egyptian parents believed this color had protective powers for their children. During the examination of a child mummy, researchers found a leather bag placed on the body. Inside, a vibrant green amulet was uncovered. Interestingly, the stone was chrysocolla.

At the time of the child's death 4,700 years ago, Egypt was still in the early stages of its history, and malachite was the most readily available green mineral. Chrysocolla, however, was rare and could only be found in the Sinai and the Eastern Egyptian Desert.

A previous grave discovery, a chrysocolla figurine of a child, supports the theory that the mineral (like the color green) was associated with children. Many experts agree that the amulet found on the toddler, who died of malaria, was likely meant to ensure health and protection in the afterlife.

5. Confirmation Of Scythian History

When archaeologist Andrei Belinski excavated a burial mound, he stumbled upon a secret that he would keep hidden for years. Situated in Russia, the mound was a kurgan, a Scythian burial site.

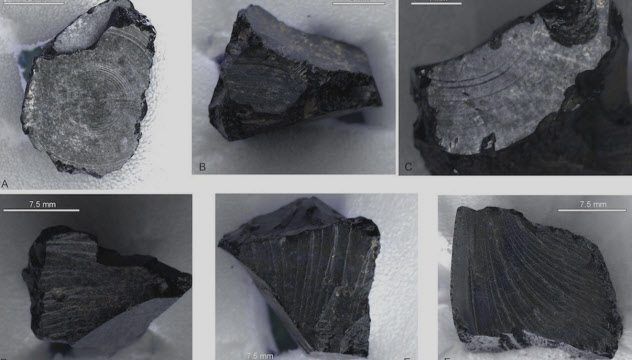

The Scythians, a fearsome nomadic people, left behind nothing but thousands of kurgans. Any new discoveries about their culture are highly valued. In 2013, Belinski's team unearthed a hidden chamber containing a stunning collection of gold jewelry and vessels. The 2,400-year-old treasure was an unexpected find. To prevent looting, the discovery was kept under wraps.

The exquisite vessels provided glimpses into the history, myths, and customs of the Scythians. Inside, a sticky black residue was found to be cannabis and opium. This discovery offers the first tangible confirmation of ancient Greek historian Herodotus's claims that the nomadic Scythians used these substances in their rituals.

The exterior of the vessel depicted scenes that might reflect their violent underworld. Another vessel portrays Scythian men locked in battle, with the elderly fighting the younger generation. This could represent the 'Bastard Wars' described by Herodotus.

Herodotus recounts that, after 28 years of battling the Persians, the men returned home to discover that their wives had given birth to children fathered by slaves. The vivid descriptions of the massacre offered researchers a valuable look at Scythian hairstyles, footwear, weapons, and even the stitching on their clothing.

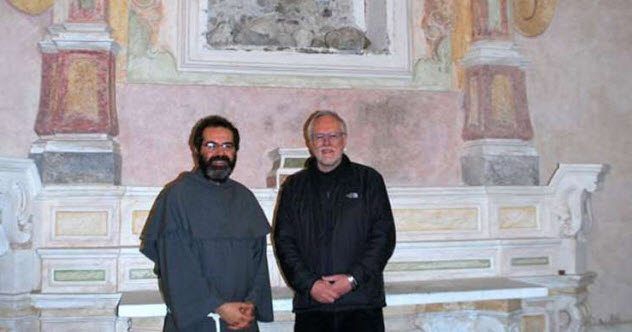

4. The Bread Of Saint Francis

In Italy, the Friary of Folloni endured a harsh and hungry winter. According to a 700-year-old legend, an angel appeared one night and left bread on the friary's doorstep.

The monks' generous benefactor was not the angel. They believed that the bread had been sent by Saint Francis of Assisi, who was in France at the time. The monks even preserved the supposed bread bag for seven centuries.

Scientists were eager to determine whether the relic truly dated back that far and, if possible, uncover traces of its original contents. The cloth's age was found to fall between 1220 and 1295, aligning perfectly with the year of the miracle in 1224.

The researchers then examined the inner surface of the cloth and discovered ergosterol, a biomarker commonly found in mold linked to processes like baking, brewing, and agriculture. It seemed likely that the medieval fabric had come into contact with bread.

Combined with the age of the relic, the findings lend support to the legend. The researchers conceded that the bread might indeed have been delivered to the struggling friary in 1224. However, since the bag had been used as an altar cloth for 300 years, it was also possible that the ergosterol was picked up from bread during that period.

3. Spontaneous Color In Manuscripts

A troublesome purple pigment is damaging scrolls worldwide. The ancient scribes never used this color, which mysteriously appears to obscure old texts and deteriorates parchment.

To unravel the mystery behind the damaging spots, researchers examined a book from the Vatican Secret Archives. This goatskin scroll, a 5-meter-long (16 ft) petition from AD 1244, had its margins stained purple, with some pages entirely obscured.

Suspecting microbial involvement, researchers collected flakes for gene sequencing. Unlike the unknown strain found in Tutankhamen’s tomb, this one was identifiable. However, when marine bacteria were discovered, it raised eyebrows—especially since the scroll’s history had no connection to the sea.

One common factor among the damaged manuscripts was that they were all made from animal hides. This led researchers to the breakthrough clue—hides had been cured with sea salt, which introduced marine organisms, including those responsible for the purple pigment.

These blooms appeared on the goatskin scroll whenever the temperature and humidity aligned perfectly. Unfortunately, some of the microbes feasted on the hide’s collagen, causing pieces to disintegrate. While the damage is irreversible, researchers remain optimistic about eventually removing the remaining pigment.

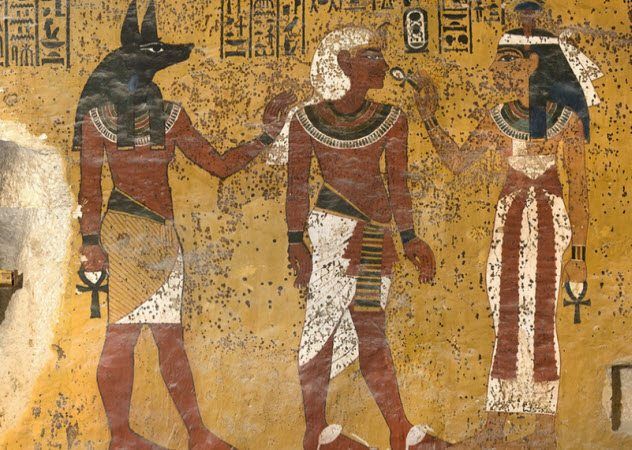

2. Tutankhamen’s Hasty Burial

In 2010, Egypt’s Supreme Council of Antiquities was thrown into a state of panic. Something unusual was happening in Tutankhamen’s tomb that they couldn’t explain. Brown blotches were appearing on nearly every surface, including paintings, plaster, and even silver.

Worried that tourists’ breathing might be fueling microbial growth, the council called in experts from Los Angeles. The spots were indeed microbial in origin, but the organisms were long dead. This led to a dual mystery.

DNA testing couldn't pinpoint the substance except for the possibility that it was a fungus. Adding an unexpected layer to the enigma of Tutankhamen, it seemed the young pharaoh had not only died abruptly around 3,000 years ago but had also been buried just as quickly.

The most plausible theory is that Tutankhamen passed away without a tomb of his own. Pharaohs typically arranged their graves long in advance of death, but in this case, an existing tomb was seized, hastily prepared, and sealed while the artwork and plaster were still damp.

This moisture, combined with the skin cells and breath of the artists, provided the perfect environment for the microbes to thrive. Interestingly, these blotches have never been discovered in any other Egyptian tomb, leaving a compelling mystery: why was the king buried in such a rushed manner?

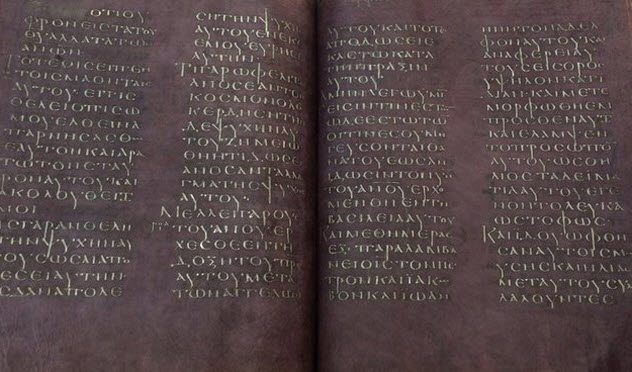

1. New Testament Dyed With Urine

Another ancient religious artifact from Italy, this time hailing from Rossano, is the Codex Purpureus Rossanensis. This partial Bible, containing only the Gospels of Matthew and Mark, is a 1,500-year-old manuscript that ranks among the earliest illuminated New Testament texts.

Scholars have long been curious about the manuscript's beautiful purple pages. In ancient times, dyes were not easy to come by. It was initially believed that the parchment was treated with a technique involving snail extract, which produced the famous Tyrian purple.

In 2016, X-ray fluorescence failed to detect bromine, the signature of Tyrian purple. Taking a bold step, scientists turned to the Stockholm papyrus, a dye recipe book from around AD 300.

After experimenting with several mixtures, they discovered a chemical match. The manuscript’s distinctive dark lavender hue came from orcein, a dye extracted from the lichen Roccella tinctoria using fermented urine. The process required ammonia, which could only come from the urine.

The same study also put to rest the idea that certain illustrations in the 188-page codex were added centuries later. Tests confirmed this theory was false, as all the intricate images were created using the same pigment palette.