Currently, the world’s attention is drawn to the Gulf Coast of the United States, where one of the most devastating industrial tragedies in history is unfolding. The explosion and subsequent sinking of the Deepwater Horizon oil rig claimed the lives of 11 workers. However, the real tragedy lies in the environmental catastrophe caused by the leakage of hundreds of thousands of barrels of oil into the Gulf of Mexico, making it one of the worst industrial environmental disasters in American history.

Industrial disasters are a byproduct of the post-industrial era, resulting from human creations. Since the onset of the industrial revolution, countless lives have been lost in industrial accidents. Many of these were preventable, caused by a reckless disregard for human safety in the pursuit of profit. Others were unforeseen and purely accidental.

This list highlights American industrial disasters that occurred post-World War II. However, as we will explore, recent events like the 2007 I-35 West Mississippi bridge collapse (13 fatalities, 145 injuries), the 2006 Sago mine tragedy (12 fatalities), the 2010 Upper Big Branch mine explosion (29 fatalities), the 2007 Crandall Canyon mine cave-in (9 fatalities), the 2008 Kingston Fossil Plant disaster (the largest coal slurry fly ash release in U.S. history), the 2008 New York City crane collapse (7 fatalities), and the 2010 Deepwater Horizon oil rig explosion (11 fatalities) are part of a long-standing pattern. Over the past 65 years, similar industrial tragedies have occurred in the United States, with no sign of these deadly catastrophes ending anytime soon. Let’s revisit the ten worst industrial disasters since 1945.

10. Silver Bridge Collapse, 1967

The Silver Bridge, a suspension structure built in 1928 and named after its aluminum coating, connected Point Pleasant, West Virginia, to Kanauga, Ohio, crossing the Ohio River. On December 15, 1967, during rush-hour traffic, the bridge collapsed, tragically killing 46 people, with two victims never recovered. Investigations into the collapse determined that the failure of a single eye bar in the suspension chain, caused by a tiny defect of just 0.1 inch (2.5 mm), was the key factor. Further analysis revealed that the bridge had been carrying far more weight than it was originally designed to withstand and had been poorly maintained. The wrecked bridge was replaced by the Silver Memorial Bridge, completed in 1969.

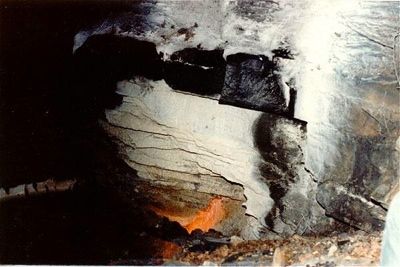

9. Centralia Mining Disaster, 1947

On March 25, 1947, the Centralia No. 5 coal mine in Centralia, Illinois, suffered a catastrophic explosion that claimed the lives of 111 miners. The explosion was triggered by a detonation of an underburdened explosive, igniting coal dust. At the time of the blast, 142 miners were inside the mine; 111 perished from burns and other injuries, while only 31 managed to escape. In the aftermath, John L. Lewis, president of the United Mine Workers, called for a two-week work stoppage by 400,000 soft-coal miners in memory of the victims. Lewis also blamed Julius Krug, the then Secretary of the Interior, for the tragedy, accusing the Department of the Interior of failing to enforce new, stricter mine safety regulations. Lewis demanded Krug’s resignation, but President Harry Truman dismissed the request, seeing the strike as a politically motivated move.

The tragedy compelled Congress to act on mine safety. In August 1947, a joint resolution was passed, urging the Bureau of Mines to conduct inspections of coal mines and report any violations of federal safety regulations to state authorities. American folk singer Woody Guthrie wrote and recorded a song about the Centralia mine disaster, titled 'The Dying Miner.'

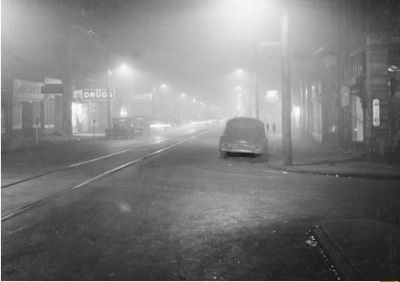

8. Donora Smog, 1948

In 1948, a different kind of industrial catastrophe struck the U.S. — one that was invisible but just as lethal as the 1947 Centralia explosion. The Donora Smog was a notorious air inversion that shrouded the town of Donora, Pennsylvania, in a toxic haze, resulting in the deaths of 20 people and the illness of 7,000 others. Donora was a mill town located on the Monongahela River, 24 miles southeast of Pittsburgh.

The smog descended on Donora on October 27, 1948. By the following day, residents began experiencing coughing and other respiratory problems. Initially, many of the illnesses and fatalities were attributed to asthma. The smog persisted until rain finally cleared it away on October 31. By then, 20 residents had died, and approximately one-third to one-half of Donora's 14,000 residents had fallen ill. Even ten years later, Donora's mortality rates were notably higher than those in nearby towns.

Frequent sulfur dioxide emissions from U.S. Steel’s Donora Zinc Works and its American Steel & Wire plant were a regular occurrence in Donora. However, what made the 1948 event particularly severe was a temperature inversion, where a layer of warm, stagnant air became trapped in the valley. This caused pollutants in the air to mix with fog, resulting in a dense, yellowish, acrid smog that lingered over Donora for five days. The sulfuric acid, nitrogen dioxide, fluorine, and other harmful gases, which typically would disperse into the atmosphere, were trapped and accumulated in the inversion until the rain broke the weather pattern.

It wasn’t until the morning of Sunday, October 31, that a meeting took place between the plant operators and town officials. The plants were shut down until the rain arrived, after which normal operations resumed. A study published in December 1948 revealed that many more residents of Donora could have died had the smog persisted longer.

U.S. Steel never took responsibility for the disaster, claiming it was 'an act of God.' The Donora Smog is often credited with sparking the clean-air movement in the United States, which ultimately led to the passage of the Clean Air Act in 1970. This legislation required the United States Environmental Protection Agency to establish and enforce regulations aimed at safeguarding the public from hazardous airborne pollutants.

7. Buffalo Creek Flood, 1972

The Buffalo Creek Flood struck on February 26, 1972, when the Pittston Coal Company’s coal slurry impoundment dam #3, located on a hillside in Logan County, West Virginia, collapsed. This disaster occurred just four days after the dam had been deemed 'satisfactory' by a federal mine inspector. The resulting flood released approximately 132 million gallons of black wastewater, creating a wave of coal ash muck that reached over 30 feet in height. It inundated 16 coal-mining hamlets in Buffalo Creek Hollow. Of the 5,000 residents, 125 were killed, 1,121 were injured, and over 4,000 were left homeless. The flood destroyed 507 houses, 44 mobile homes, and 30 businesses, also causing damage to homes in six surrounding towns. Pittston Coal later referred to the disaster as 'an Act of God' in its legal filings.

Dam #3, built with coarse mining refuse dumped into the Middle Fork of Buffalo Creek starting in 1968, was the first to fail after heavy rains. The water from Dam #3 then overwhelmed the nearby Dams #2 and #1. This dam had been constructed on top of coal slurry sediment accumulated behind Dams #1 and #2, rather than on solid bedrock. Dam #3 was situated about 260 feet above the town of Saunders when it gave way.

6. Willow Island Disaster, 1978

The Willow Island disaster occurred on April 27, 1978, when a cooling tower under construction at a power station in Willow Island, West Virginia, collapsed. The falling concrete caused the scaffolding to collapse as well, resulting in the deaths of 51 construction workers. This is believed to be the deadliest construction accident in American history. The tragedy took place while the Allegheny Power System was building a new power plant with two massive natural draft cooling towers. The typical method of scaffold construction for large towers involves building the base on the ground and raising the top to match the tower’s height as construction progresses.

The scaffolding used at Willow Island was unlike typical construction scaffolding. It was bolted directly to the structure as construction progressed. After each layer of concrete was poured, the concrete forms were removed and the scaffolding was raised and bolted to the newly added section. On April 27, 1978, Tower 2 had reached a height of 166 feet. Just after 10 AM, as the third concrete lift was being raised, the cable hoisting the concrete bucket went slack. The crane pulling the bucket collapsed toward the inside of the tower. The previous day's concrete (Lift 28) began to collapse. The concrete unwrapped from the top of the tower in a counter-clockwise motion, followed by both directions. A mix of concrete, wooden forms, and metal scaffolding fell into the hollow center of the tower, resulting in the deaths of 51 construction workers.

The Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) investigation revealed that, as with many disasters, a combination of errors, shortcuts, and accidents led to the tragedy. The scaffold was attached to concrete that hadn't sufficiently cured. Some bolts were missing, and others were not of the appropriate grade. There was only a single access ladder, severely limiting escape options. The concrete hoisting system had been modified without proper engineering review. As is often the case, contractors were rushing to expedite construction.

5. L’Ambiance Plaza Collapse, 1987

A major construction disaster occurred nine years later at the L’Ambiance Plaza, a 16-story residential building under construction in Bridgeport, Connecticut. The building’s partially constructed frame collapsed completely on April 23, 1987, killing 28 workers. The cause was believed to be the high stress placed on the floor slabs due to the lift slab construction technique. Some believed this event exposed the flaws in the lift slab method. This disaster led to a nationwide federal investigation into the technique and a temporary ban on its use in Connecticut. The L’Ambiance Plaza was designed as a 16-story building with 13 apartment levels and three parking levels, consisting of two offset rectangular towers, each measuring 63 feet by 112 feet, connected by an elevator.

At the time of the collapse, the construction of the building was just past its halfway point. In the west tower, the ninth, tenth, and eleventh floor slab package had been positioned in stage IV, directly beneath the twelfth floor and roof package. The shear walls were located about five levels below the lifted slabs. Workers were in the process of tack welding wedges under the ninth, tenth, and eleventh floor slabs to temporarily hold them in place when they suddenly heard a loud metallic noise followed by rumbling. One of the ironworkers, who was installing wedges at that moment, looked up to see the slab above him 'cracking like ice breaking.' Without warning, the slab fell onto the slab below it, which couldn't support the added weight and collapsed in turn.

The entire structure fell apart within five seconds, starting with the west tower and then the east tower. This collapse took only 2.5 seconds longer than it would have for an object to free-fall from that height. After two days of frantic rescue operations, it was confirmed that 28 construction workers had died in the disaster, making it the deadliest lift-slab construction accident in history.

4. Imperial Sugar Refinery Explosion, 2008

The Imperial Sugar refinery explosion, which took place on February 7, 2008, in Port Wentworth, Georgia, was a devastating industrial disaster. Thirteen people lost their lives, and 42 others were injured in a dust explosion at the Imperial Sugar facility. Dust explosions had been a known hazard in the United States, particularly after three fatal accidents in 2003, prompting authorities to take action to improve safety standards and reduce the risk of such incidents. Despite these efforts, a safety board had criticized them as insufficient to prevent such tragedies.

The sugar refinery, a four-story facility located along the Savannah River, was the second largest of its kind in the United States. Workers often referred to the plant as outdated, with much of its machinery being over 28 years old. Despite its age, the site remained in operation due to its advantageous access to rail and shipping routes for transportation. At its peak, the refinery processed 9% of the nation's sugar. The explosion occurred at 7:00 p.m. local time in what was initially believed to be a room where sugar was being bagged by workers. At the time of the incident, there were 112 employees on-site, with victims ranging in age from 18 to 50, most of whom sustained severe burns.

By February 14, 2008, the worst of the fire had been put out, but the 100-foot sugar storage silos were still burning despite efforts to extinguish the flames. The molten, smoldering sugar inside the silos presented an unprecedented challenge for firefighters. The factory's outdated construction materials, including a wooden tongue-and-groove ceiling and creosote used throughout, contributed significantly to the severity of the fire. The creosote, also known as 'fat lighter,' posed an especially high fire risk. As a result of this tragedy, new safety legislation was proposed, although the local economy suffered due to the factory’s closure. Imperial Sugar has since announced plans to rebuild.

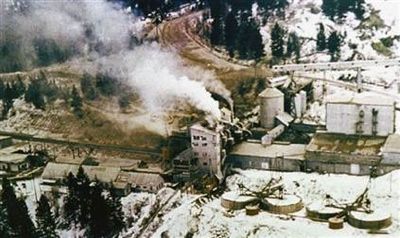

3. Montana Vermiculite Contamination, 1999 to Present

Vermiculite, an ore discovered in Libby, Montana, in 1881, had been mined since 1919 and sold under the brand name Zonolite. The mineral, primarily used as an insulator in homes and as an additive in potting soil, posed a serious health risk due to its contamination with asbestos. This issue was known to the company for many years, even before W. R. Grace and Company acquired the Zonolite mine in 1963.

In 1999, the Seattle Post-Intelligencer ran a series of articles that revealed a disturbing truth: deaths and illnesses caused by asbestos-contaminated vermiculite mined in Libby, Montana, affected not only the workers but also the residents of the town. This was especially alarming because asbestos exposure usually affects those who work with the material in plants, mines, or ships, with workers often bringing the harmful dust home on their clothes. However, in Libby, people were getting sick and dying from diseases such as asbestosis and mesothelioma—diseases that are exclusively caused by asbestos exposure—even though they had never worked in the mine or plant or had any direct contact with someone who did. The discovery of asbestosis in individuals without a known industrial exposure was unprecedented until the Libby vermiculite disaster came to light.

It was later revealed that the mine owners were aware that the vermiculite ore extracted from the Libby mine was contaminated with tremolite, a particularly dangerous form of asbestos. Despite knowing that they could not remove the asbestos contamination, W.R. Grace continued to mine and process the vermiculite, shipping it by rail to various other plants and manufacturers. They were fully aware of the deadly risks associated with the asbestos-laced vermiculite, yet they exposed their workers, the local residents of Libby, and employees at other manufacturing sites to the harmful substance.

The true toll of asbestos-related deaths remains unknown. A study comparing the mortality rates in Libby to those in Montana and the rest of the United States between 1979 and 1998 found a 20-40% increase in both malignant and non-malignant respiratory deaths among Libby residents. However, no one can determine the exact number of people who died from asbestos exposure due to the vermiculite shipped from Libby to other parts of the country.

According to the EPA, more than 274 deaths in the Libby area were attributed to asbestos-related diseases. A significant 17% of Libby residents who underwent testing were found to have pleural abnormalities, which may be linked to asbestos exposure. In February 2005, the Federal Government launched a criminal conspiracy case against W.R. Grace and seven current and former employees. The government accused Grace of conspiring to conceal the dangers of asbestos from its workers and the town’s residents, while knowingly releasing asbestos into the environment. However, on May 8, 2009, a jury acquitted W.R. Grace and the accused employees on all charges, bringing an end to what was described as the largest environmental-crime prosecution in U.S. history.

2. Texas City Disaster, 1947

The BP refinery explosion was not the worst industrial catastrophe to hit Texas City or even the state. 1947 proved to be an especially tragic year for industrial disasters. Just three weeks after the Centralia Mining Disaster, on April 16, 1947, a fire broke out aboard the French-registered vessel SS Grandcamp in the Port of Texas City, Texas. The fire ignited approximately 2,300 tons of ammonium nitrate, leading to a catastrophic series of explosions and fires that claimed at least 581 lives.

Another ship, the SS High Flyer, was docked nearby, approximately 600 feet from the Grandcamp. The High Flyer contained 961 tons of ammonium nitrate and 1,800 tons of sulfur. The ammonium nitrate in both vessels and the adjacent warehouse was fertilizer destined for European farmers. At around 08:10, smoke was spotted coming from the Grandcamp’s cargo hold, but efforts to extinguish the fire were unsuccessful.

Just before 9:00 AM, the Captain ordered his crew to steam the hold, a firefighting technique where steam is pumped into the ship’s hold to extinguish the fire while attempting to save the cargo. Meanwhile, a crowd of spectators gathered on the shoreline, believing they were at a safe distance. The water around the ship was already boiling from the heat, signaling runaway chemical reactions. The cargo hold and deck began to bulge as internal pressures mounted.

At 09:12 AM, the ammonium nitrate on board the Grandcamp detonated. The explosion created a massive shockwave, sending a 15-foot tidal wave that could be felt up to 100 miles along the Texas coastline. The blast obliterated the Monsanto Chemical Company plant and ignited nearby refineries and chemical storage tanks. The force of the explosion was so powerful that planes flying nearby had their wings torn off. The shockwave was felt as far as 250 miles away in Louisiana. Tragically, the entire volunteer fire department of Texas City perished in the initial blast.

But the disaster didn’t end there. The initial explosion triggered another detonation in the High Flyer’s ammonium nitrate cargo. Efforts to salvage the ship failed, and attempts to tow it out of the harbor were unsuccessful. About fifteen hours after the explosions aboard the Grandcamp, the High Flyer exploded as well, claiming at least two more lives and causing additional damage to the port and other vessels.

The Texas City Disaster is widely regarded as the deadliest industrial accident in U.S. history. Witnesses likened the destruction to the aftermath of the Nagasaki bombing. The official death toll was recorded at 581, though 63 of the deceased were never identified. Additionally, 113 people were classified as missing, as no identifiable remains were ever found. Some speculate that the true number of casualties could be much higher, including uncounted seamen, temporary workers, their families, and travelers passing through.

Over 5,000 individuals were injured in the disaster, with 1,784 requiring hospitalization across 21 local hospitals. More than 500 homes were destroyed, and hundreds more were damaged, leaving 2,000 people homeless. The seaport itself was obliterated, with property damage estimated at a staggering $100 million. A two-ton anchor from the Grandcamp was hurled 1.62 miles, landing in a 10-foot crater, and it now serves as a memorial in a local park.

1. Texas City Refinery Explosion 2005

On March 23, 2005, a catastrophic fire and explosion rocked BP's Texas City Refinery in Texas City, Texas, resulting in the deaths of 15 workers and leaving more than 170 injured. BP was found guilty of violating federal environmental crime regulations and faced lawsuits from the victims' families. In the aftermath, the US Occupational Safety and Health Administration levied an $87 million fine on BP, citing the company's failure to implement crucial safety improvements following the disaster.

The Texas City Refinery stands as the second-largest oil refinery in Texas and the third-largest in the United States. The explosion occurred in a unit responsible for separating light and heavy gasoline components, during which octane was being added. A failure in operator judgment led to gasoline being directed into a blow down drum, a pressure relief system. The pressure became excessive and overwhelmed the system, causing gasoline to spill and form a highly combustible vapor cloud. This vapor cloud was ignited by a contractor's nearby pickup truck. An official investigation uncovered numerous deficiencies, including poor equipment maintenance, inadequate risk management, weak staff oversight, and a problematic safety culture at the site.

In response to the incident, an independent panel was formed to examine the safety culture and management systems at BP North America, led by former US Secretary of State James Baker III. The panel's report, published on January 16, 2007, found that BP had failed to distinguish between 'occupational safety' (such as slips, trips, and falls) and 'process safety' (including equipment design, hazard analysis, and material verification). BP mistakenly believed improvements in occupational safety translated to overall safety improvements. Furthermore, the company opted not to replace the outdated blow down system with a more modern, safer version, which could have prevented the explosion by preventing the excess gasoline from spilling onto the ground.

Above Ground Nuclear Testing 1951-1962

Though not a single event like the others, this disaster unfolded over a span of twelve years, with each nuclear detonation adding to the industrial-scale catastrophe. The full extent of the human impact of the roughly 200 above-ground nuclear weapons tests carried out in the western United States, primarily at the Nevada Proving Grounds, may never be fully known. However, what is certain is that these detonations released a total of 153.8 megatons of TNT worth of explosive power, along with vast amounts of radioactive fallout, contaminating not only a significant portion of the United States but also spreading across the globe.

From 16 July 1945 to 23 September 1992, the United States maintained an aggressive nuclear testing program. The majority of these tests were atmospheric (above-ground) until November 1962. After the adoption of the Partial Test Ban Treaty, all testing was moved underground to contain the nuclear fallout. The atmospheric tests, however, exposed a large portion of the U.S. population to hazardous fallout, and pinpointing the precise number of people affected, and the exact consequences, has been a challenging task for medical research.

A 1979 study published in the New England Journal of Medicine concluded that there was a significant increase in leukemia deaths among children up to 14 years old living in Utah between 1959 and 1967. This excess was particularly evident in children born between 1951 and 1958, especially those residing in counties that received higher levels of fallout.

According to a 1997 report by the National Cancer Institute, ninety atmospheric tests at the Nevada Test Site (NTS) released significant amounts of radioactive iodine-131 into the atmosphere, affecting a large portion of the contiguous United States. Particularly in 1952, 1953, 1955, and 1957, these doses were substantial enough to potentially cause between 10,000 and 75,000 cases of thyroid cancer.

Radioactive fallout from Cold War nuclear tests around the world likely caused at least 15,000 cancer deaths among U.S. residents born after 1951, according to data from an unpublished federal study. A significant portion of the radioactive fallout Americans were exposed to originated from U.S. above-ground nuclear weapons tests.

The research, along with previous government investigations, suggests that fallout from above-ground nuclear weapons tests is linked to at least 20,000 non-fatal cancers, and potentially many more. The study highlights that fallout from numerous U.S. tests at the Nevada Test Site spread significant levels of radioactivity across large areas of the country. When considering fallout from both domestic and international tests, it becomes clear that no U.S. resident born after 1951 was spared from exposure.