The creator of this list does not claim expertise in the literary traditions of every language worldwide. With over 6,000 languages in existence, additional suggestions and contributions are encouraged. The entries are presented in no specific order, and readers are invited to propose notable omissions or highlight exceptional writers from their own languages if they are not included here.

10. Latin Publius Vergilius Maro

Honorable mentions: Marcus Tullius Cicero, Gaius Julius Caesar, Publius Ovidius Naso, Quintus Horatius Flaccus

Vergil is best remembered for The Aeneid, his epic poem chronicling the fall of Troy and the establishment of Rome by Aeneas. Known as one of history's most meticulous perfectionists, Vergil composed The Aeneid at a painstaking pace of just three lines per day. This deliberate speed ensured that no better phrasing could exist for each line. Latin's flexible syntax, allowing clauses to be arranged in almost any order, granted Vergil immense creative freedom in crafting the poem's rhythm and sound without altering its meaning. He meticulously explored every possible option at every stage of composition.

In addition to The Aeneid, Vergil contributed two other masterpieces to Latin literature: the Eclogues (circa 38 BC) and the Georgics (circa 29 BC). The Georgics, a collection of four didactic poems on agriculture, offers practical advice, such as avoiding planting grapevines near olive trees due to the latter's high flammability during dry summers. Vergil also celebrated Aristaeus, the god of beekeeping, highlighting honey's importance as Europe's sole sugar source before Caribbean sugar cane arrived. He even detailed a method for acquiring a beehive: by sacrificing a deer, boar, or bear, leaving its carcass in the woods, and praying to Aristaeus, who would send bees to inhabit it within a week.

Vergil's will expressed his desire for The Aeneid (19 BC) to be destroyed after his death, as he considered it incomplete. However, Caesar Augustus intervened and preserved the work.

9. Ancient Greek Homer

runners-up: Plato, Aristotle, Thucydides, Paul of Tarsus, Euripides, Aristophanes

Should these rankings follow an ascending sequence, Homer would likely claim the top spot. He might have been a solitary blind storyteller whose tales were transcribed four centuries later. Alternatively, he could represent a collective effort spanning generations, with numerous contributors enriching the narratives of the Trojan War and Odysseus's subsequent adventures.

Regardless, the foundation of Ancient Greek literature is deeply rooted in The Iliad and The Odyssey (both circa 750 BC). The language used in these epics is termed Homeric, distinguishing it from the later Attic and Koine dialects. The Iliad focuses on the final decade of the Greek siege of Troy (Ilion), centering on the destructive wrath of Achilles, provoked by Agamemnon's disrespect and appropriation of Achilles' war spoils. This fury leads Achilles to withdraw from battle, resulting in significant Greek losses.

Eventually, Patroclus, Achilles' closest companion (and likely romantic partner), unable to endure the stalemate, enters the battle seeking honor but meets his end at Hector's hands. Enraged, Achilles re-enters the war, unleashing havoc among the Trojan ranks, confronting even the river god Xanthus. After slaying Hector, the epic concludes with funeral rites for both Patroclus and Hector.

The Odyssey stands as a peerless epic of exploration, employing innovative flashbacks to narrate Odysseus's decade-long quest to return home. The fall of Troy is revisited when Odysseus encounters the spirits of the deceased, including Achilles, during his descent into the underworld.

Homer's legacy is encapsulated in these two surviving works, which have become the cornerstone of Western literature. Composed in dactylic hexameter, now revered as the heroic or Homeric meter, these epics have inspired more poetic tributes in the Western canon than any other figure, save for Jesus and the Virgin Mary.

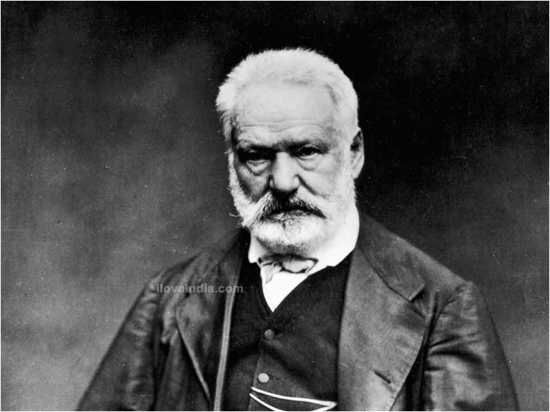

8. French Victor Marie Hugo

runners-up: Rene Descartes, Voltaire, Amexandre Dumas (pere), Moliere, Francois Rabelais, Marcel Proust, Charles Baudelaire

The French literary tradition cherishes expansive novels, with Marcel Proust's *In Search of Lost Time* standing as the most voluminous. Yet, Victor Hugo reigns as the quintessential master of 19th-century French prose and poetry. His monumental works, *Notre Dame de Paris* (1831) and *Les Misérables* (1862), cement his legacy. The former, often referred to as *The Hunchback of Notre Dame*, diverges sharply from its Disney adaptation, presenting a tragic narrative where Quasimodo endures relentless misfortune.

Quasimodo harbors deep affection for Esmeralda, who treats him with kindness. However, Frollo, the malevolent priest, also desires her. Upon witnessing her near-intimacy with Captain Phoebus, Frollo frames her for Phoebus's attempted murder—a crime he himself orchestrated. Esmeralda endures the brutal Spanish boot torture, which mercilessly crushes her foot until she falsely confesses. Sentenced to death, she is saved at the last moment by Quasimodo.

Mistaking Quasimodo for the villain, the townsfolk rally to storm Notre Dame and free Esmeralda. Frollo dispatches the king’s guards to reclaim her. After she rejects his advances, he hands her over to be executed. As she hangs, Frollo revels in her demise until Quasimodo hurls him from the bell tower to his death. Quasimodo then mourns over Esmeralda’s body in the mass grave at Montfaucon, where he remains until he perishes from starvation. A year and a half later, an attempt to separate their intertwined skeletons causes them to disintegrate into dust.

*Les Misérables*, translating to 'The Miserable Ones,' offers little more optimism, akin to Dickens’s *Oliver Twist*. However, Cosette survives, enduring a lifetime of suffering shared by nearly every character in the tale. The novel critiques rigid legalism, embodied by Javert, and highlights the widespread neglect of society’s most vulnerable.

7. Spanish Miguel de Cervantes Saavedra

runners-up: Jorge Luis Borges

Cervantes’s greatest work is *El ingenioso hidalgo don Quijote de la Mancha* (1605, 1615), also known as *The Ingenious Gentleman Don Quixote of La Mancha*. His literary contributions also include a series of short stories, the pastoral romance *La Galatea*, and the adventurous tale *The Travails of Persiles and Sigismunda*.

*Don Quixote* remains uproariously funny even today. The protagonist, Alonso Quijano, becomes so engrossed in tales of chivalric romance that he embarks on a quest to revive the age of knights and damsels. Accompanied by his loyal squire, Sancho Panza, a humble farmer, Quixote’s escapades are both absurd and endearing. Sancho serves as a grounding force, offering a stark contrast to Quixote’s delusions and reminding readers of the real world.

Quixote’s antics include tilting at windmills, attempting to save individuals who don’t require assistance, and enduring numerous beatings. The second volume, released a decade after the first, is often regarded as a pioneering piece of modern literature. In this sequel, the characters are aware of Quixote’s exploits from the first book, leading to deliberate attempts to mock and challenge his ideals. Ultimately, Quixote is defeated by the Knight of the White Moon, returns home, and succumbs to illness. On his deathbed, he bequeaths his fortune to his niece, stipulating that she must never marry a man who indulges in chivalric fantasies.

6. Dutch Joost van den Vondel

runners-up: Pieter Hooft, Jacob Cats

Vondel stands as the most celebrated writer in Dutch history, a poet and playwright who reached the heights of the Dutch Golden Age. His most famous work, *Gijsbrecht van Amstel*, a historical drama, was staged annually on New Year’s Day in Amsterdam from 1638 to 1968. The play recounts the tale of Gijsbrecht IV, who, in the narrative, invades Amsterdam in 1303 to reclaim his family’s honor and establish a barony. However, Vondel’s historical accuracy falters, as the invasion was actually led by Gijsbrecht’s son, Jan, the true hero who overthrew the region’s oppressors. Despite this, Gijsbrecht remains a national icon, a fact that would likely amuse Vondel, renowned for his comedic genius.

Vondel’s magnum opus, the epic poem *Joannes de Boetgezant* (1662), or *John the Baptist*, chronicles the life of the biblical figure and is hailed as the National Epic of the Netherlands. To draw a parallel for American readers, imagine the cultural significance of a single work representing the nation—contenders might include *Moby Dick*, *The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn*, or *The Scarlet Letter*. Vondel’s stature in Dutch culture is akin to the combined reverence for these classics. Additionally, his play *Lucifer* (1654) delves into the biblical character’s motivations and psyche, offering a profound exploration of his actions. This work heavily influenced John Milton’s *Paradise Lost*, published 13 years later in 1667.

5. Portuguese Luis Vaz de Camoes

runners-up: Eca de Queiroz, Fernando Pessoa

Camoes is celebrated as Portugal’s national poet, whose verse rivals the greatest works in European literature. His crowning achievement, *Os Lusiadas* (1572), or *The Lusiads*, derives its name from the inhabitants of ancient Lusitania, now Portugal. The term traces back to Lusus, a companion of Bacchus, the wine god, believed to be the progenitor of the Portuguese people. This epic, composed in ottava rima, consists of ten books, each stanza following the ABABABCC rhyme scheme.

The poem chronicles Portugal’s legendary maritime expeditions, exploring, conquering, and colonizing distant lands. Drawing parallels to Homer’s *Odyssey*, Camoes pays homage to both Homer and Virgil throughout. The narrative centers on Vasco da Gama’s voyage, weaving in historical events like the Revolution of 1383-85 and da Gama’s trade endeavors in Calicut, India. Under the watchful eyes of Greek deities, da Gama, a devout Catholic, prays to his God. The epic concludes with a nod to Magellan and the promising future of Portuguese naval exploration.

4. German Johann Wolfgang von Goethe

runners-up: Friedrich von Schiller, Arthur Schopenhauer, Richard Wagner, Heinrich Heine, Franz Kafka

Goethe is as central to German literature as Bach is to German music. Every significant writer after Goethe either referenced him or built upon his ideas to shape their own literary paths. His prolific output includes four novels, countless poems, nonfiction works, and scientific essays. His most renowned piece, *The Sorrows of Young Werther* (1774), sparked the “Sturm und Drang” movement in German Romanticism. Beethoven’s 5th Symphony, for instance, resonates deeply with the emotional intensity of *Werther*.

*Werther* narrates the tragic tale of its protagonist’s unrequited love, culminating in his suicide. Written in an epistolary format, it popularized the style for over a century. Goethe’s magnum opus, however, is *Faust*, published in two parts (1808 and 1832). While the Faust legend predates Goethe, his rendition remains the most globally recognized.

Faust, a scholar whose intellect impresses God, becomes the subject of a wager between God and Mephistopheles (Satan). The story echoes the Book of Job, with Faust striking a blood pact with Satan, trading his soul for earthly desires. Rejuvenated, Faust falls for Gretchen, but tragedy ensues when a potion he provides accidentally kills her mother. Gretchen, driven mad, drowns her child and faces execution. Despite Faust and Satan’s attempt to free her, Gretchen chooses to stay, earning God’s forgiveness as she awaits her fate.

Part 2 of *Faust* demands a deep familiarity with Greek mythology, presenting a challenging read. It expands on the Gretchen narrative from Part 1, depicting Faust’s rise to immense power and corruption with Satan’s aid. In the end, Faust recalls the joy of virtue and dies instantly. As Satan claims his soul, angels intervene, transporting everyone to a heavenly mountain where Pater Profundus illustrates human nature through a parable. Angels advocate for Faust’s soul, leading to his rebirth and ascension to Heaven. Gustav Mahler immortalized this climactic scene in the second part of his 8th Symphony.

3. English William Shakespeare

runners-up: John Milton, Samuel Beckett, Geoffrey Chaucer, Virginia Woolf, Charles Dickens

Voltaire famously dismissed Shakespeare as “that drunken fool” and his works as “this enormous dunghill.” Despite such criticism, Shakespeare’s impact on global literature is undeniable. His influence extends beyond English, reaching into numerous languages worldwide. He holds the title of the most translated author, with his complete works available in around 70 languages and individual plays and poems translated into over 200.

Approximately 60% of the English language’s popular phrases, quotes, and idioms originate from the King James Bible, while over 30% stem from Shakespeare. Examples include “It was Greek to me” (*Julius Caesar*), “all the world’s a stage” (*As You Like It*), “one who loved not wisely but too well” (*Othello*), “the wheel is come full circle” (*King Lear*), and “you’re a real piece of work” (*Hamlet*).

In Shakespeare’s era, tragedies typically concluded with the death of at least one main character, and in the most impactful ones, nearly everyone perishes (*Hamlet* – c. 1599-1602, *King Lear* – c. 1606, *Othello* – c. 1603, *Romeo and Juliet* – c. 1597). Conversely, comedies often ended with the marriage of two central characters, and in the best comedies, multiple couples wed (*A Midsummer Night’s Dream* – c. 1596; *Much Ado About Nothing* – c. 1599; *The Merry Wives of Windsor* – c. 1602). Shakespeare masterfully aligns character tensions with the plot, ensuring that climactic moments feel inevitable and authentic, rather than forced or gratuitous. His ability to depict human nature remains unparalleled.

The brilliance of Shakespeare’s works—his sonnets, plays, and poems—lies in their profound cynicism. While he often extols humanity’s highest virtues, these ideals are framed within an idealized world. Simultaneously, he “holds up the mirror to nature,” reflecting our flaws without alienating the audience. Characters like Othello, Hamlet, Lear, Brutus, Beatrice, and Benedick embody the best and worst of human nature, making them timeless and relatable.

2. Italian Durante degli Alighieri

runners-up: none

The title includes Dante Alighieri’s full name, with “Alighieri” being the contemporary spelling of his father’s name, Alaghiero or Alighiero. “Dante” is a diminutive of “Durante,” derived from Latin, meaning “enduring” or “everlasting.” Dante played a pivotal role in unifying Italy’s diverse dialects into modern Italian. The Tuscan dialect, native to Florence where Dante was born, became the standard for all of Italy due to *La Divina Commedia* (1321), or *The Divine Comedy*. This masterpiece stands as one of the world’s greatest literary achievements.

During Dante’s era, Italy’s regions each had their own dialects, with Tuscan differing significantly from, for instance, Venetian. Today, learners of Italian as a foreign language typically start with the Florentine variant of Tuscan, largely because of *The Divine Comedy*’s influence. The poem’s narrative is widely known: Dante journeys through Hell and Purgatory, guided by #10, to witness the punishments meted out for various sins. Each punishment exemplifies “contrapasso,” where the penalty mirrors the crime. For example, the lustful are eternally buffeted by winds, reflecting their lack of control in life, while schismatics, like Mohammed, are repeatedly split open by a demon’s sword, symbolizing their divisive actions.

Dante’s portrayal of Heaven in *Paradiso* is equally unforgettable, structured around the Ptolemaic model of nine concentric spheres. Each level brings Dante and his guide, Beatrice, closer to God. After encountering biblical figures, Dante finally beholds God as three luminous circles, distinct yet unified, from which Jesus, the human embodiment of God, emerges.

Beyond *The Divine Comedy*, Dante penned shorter poems and essays, including *De Vulgari Eloquentia*, advocating for a unified Italian vernacular akin to Latin. He also wrote *La Vita Nuova*, or *The New Life*, blending poetry and prose to celebrate chivalric love. No other writer has shaped a language as profoundly as Dante has shaped Italian.

1. Russian Alexander Sergeyevich Pushkin

runners-up: Leo Tolstoy, Anton Chekhov, Fyodor Dostoyevsky

Pushkin is celebrated as the pioneer of distinctly Russian literature, setting it apart from earlier works influenced by Western European styles. Primarily a poet, Pushkin excelled in all genres, with his most notable works being *Boris Godunov* (1831) and *Evgeny Onegin* (1825-32). The former is a play, while the latter is a novel in verse, composed entirely in sonnets. Pushkin introduced a unique sonnet form for *Onegin*, differing from those of Petrarch, Shakespeare, and Spenser, with the rhyme scheme AbAbCCddEffEgg. Here, uppercase letters denote feminine rhymes (e.g., “grainy/rainy”), and lowercase letters represent masculine rhymes (e.g., “grain/rain”).

Eugene Onegin, the protagonist, serves as the archetype for Russian literary heroes. He embodies the “superfluous man,” a figure who rejects societal norms and responsibilities. Onegin drifts through life, engaging in gambling and duels, and can be described as a sociopath—not in a violent or malevolent sense, but as someone indifferent to societal values. His character remains a quintessential example in Russian literature. Many of Pushkin’s works have been adapted into operas and ballets, though translating *Onegin* is notoriously challenging due to the inherent difficulties of preserving poetic uniqueness and sound across languages. For instance, while English has one word for snow, an Inuit dialect has 45, highlighting the complexities of linguistic translation.

As a result, *Onegin* has been translated into numerous European languages, with Vladimir Nabokov’s English version expanding the text to four volumes. Nabokov prioritized preserving definitions and connotations but sacrificed the poetic rhythm. Pushkin’s innovative writing style, which explored the Russian language’s depths and introduced new grammatical and syntactical concepts, established conventions that continue to influence Russian writers to this day.