Imagine diving deep into the water and suddenly discovering a river beneath the surface. Strange, right? But such natural wonders do exist in the world.

Underwater rivers aren't the only oddities beneath the waves. There are also lakes beneath glaciers, waterfalls hidden beneath the ocean, and even oceans buried deep inside the Earth's crust. Here are ten remarkable bodies of water—rivers, lakes, and waterfalls—situated beneath other rivers, oceans, or glaciers.

10. Cenote Angelita

Cenote Angelita (which means 'Little Angel') is a cenote located in Mexico’s Yucatan Peninsula. A cenote is similar to a sinkhole, but it’s filled with water. It forms when a soft limestone layer collapses, revealing the groundwater below.

Cenote Angelita actually houses a saltwater river at its base. A halocline, a dangerous cloud of hydrogen sulfide, separates the fresh water above from the saltwater beneath, creating a mixture of both.

The halocline is so foggy that you can't see through it without a light. It’s also toxic. Not only does it serve as a natural divider between fresh and saltwater, but it also acts as a pseudo-seabed for the freshwater portion, preventing lighter objects from sinking through to the saltwater below.

9. Lake Whillans

Lake Whillans lies beneath the Ross Ice Shelf in Western Antarctica. Scientists estimate its depth to be between 10 and 25 meters (33–82 ft), though initial drilling in January 2013 revealed it to be only 2 meters (6.6 ft) deep. However, this doesn’t rule out deeper areas elsewhere in the lake.

Water samples taken from the lake showed the existence of microbes that have adapted to life without sunlight. These microbes survive by consuming fossilized pollen buried under the ice for more than 34 million years.

After drilling 730 meters (2,400 ft) to reach a 10-meter-deep (33 ft) body of water at a nearby site, scientists discovered more microbes, crustaceans, and small, peculiar-looking fish with large eyes. While the reason for their oversized eyes is unclear, it could be linked to their dark environment.

The largest of these fish were also translucent, with their internal organs visible from the outside. This lack of color is thought to result from a deficiency of hemoglobin, the protein that gives blood its red color. However, scientists were unable to confirm whether this translucent fish represented a new species.

8. Hamza River

A river flows 4,000 meters (13,000 ft) beneath the Amazon River in Brazil. This river stretches 5,950 kilometers (3,700 mi) in length, making it long, though still shorter than the Amazon. It is informally referred to as the Hamza River, named after geophysicist Valiya Hamza.

While the Amazon surpasses the Hamza in length, the latter outshines the former in width. At its narrowest, the Hamza spans 200 kilometers (125 mi), and at its widest, it reaches 400 kilometers (250 mi), dwarfing the Amazon. However, the Amazon outperforms the Hamza in nearly every other aspect. The Hamza’s water flows at a rate of one million gallons per second, significantly lower compared to the Amazon’s flow of 35 million gallons per second.

Water in the Hamza moves at a glacial pace, traveling no more than 100 meters (330 ft) per year. This has led some scientists, including Professor Hamza, to suggest that it may not qualify as a river in the traditional sense. A mere 100 meters per year is exceptionally slow for a river—glaciers cover more ground in that time. The Hamza’s sluggish flow could be due to its passage through porous rocks, unlike the Amazon's open-water path.

7. Denmark Strait Cataract

If you search for “the highest waterfall in the world,” Angel Falls in Canaima National Park, Venezuela, is likely to appear. Standing at 979 meters (3,212 ft), Angel Falls is remarkably high—so high that some of its water evaporates before it hits the ground. However, it can’t compare to the Denmark Strait Cataract, which plunges 3,500 meters (11,500 ft) beneath the Atlantic Ocean, located between Greenland and Iceland.

The Denmark Strait Cataract occurs when the cooler waters of the Greenland Sea meet the warmer waters of the Irminger Sea. Upon their meeting, the cooler, denser Greenland Sea waters quickly descend to the ocean floor, forming the waterfall. After hitting the seabed, the water does not stay in place; it flows south, rises to the surface, and replaces the warmer waters heading north, continuing the cycle.

6. Unnamed River Under The Black Sea

A river flows beneath the Black Sea, and it is no ordinary underwater river. This river has waterfalls and rapids along its path. Were it located above ground, it would be the sixth-largest river in the world by water flow, carrying ten times more water than the Rhine, Europe’s largest river.

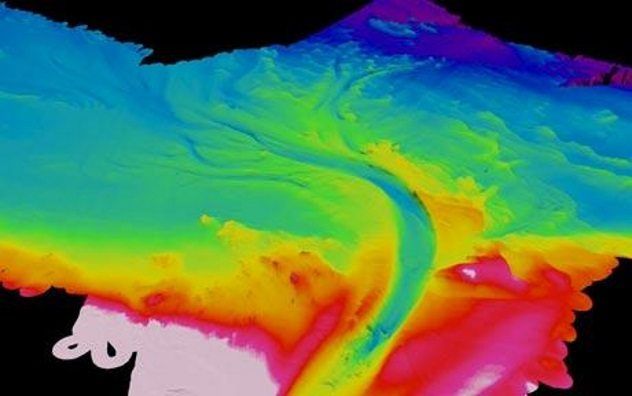

The river reaches depths of up to 35 meters (115 ft) and spans 1 kilometer (0.6 mi) in width, flowing along the Black Sea floor. Its high salinity prevents the river’s water from mixing with the surrounding Black Sea waters. Scientists from the University of Leeds tracked it using a robot submarine for 60 kilometers (37 mi) before it dissipated into the deep sea.

5. Nigardsbreen Ice Cave Pond

Ice caves are natural formations within glaciers, created when water melts an opening, allowing it to pass through the glacier. The water may come from the glacier itself or from a nearby river or ocean where the glacier meets. These ice caves are typically found in countries near the Arctic and Antarctica, with Norway and Iceland being particularly popular among tourists.

In 2007, a remarkable ice cave was discovered in the Nigardsbreen glacier range in Norway. This cave features a chamber 8 meters (26 ft) tall and spans 20 by 30 meters (66 x 98 ft). It even houses a pond, formed when melting water from the glacier created an entry point, accumulating under the glacier because there was no place for the water to flow. The pond’s warmth further accelerates the glacier’s melting from within, enlarging the volume of water.

4. Hot Tub Of Despair

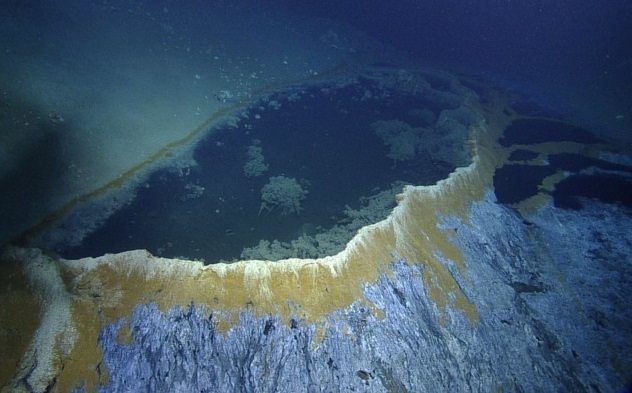

The Hot Tub of Despair is a brine pool located 1,000 meters (3,300 ft) beneath the surface of the Gulf of Mexico. Scientists speculate that it formed millions of years ago when the Gulf dried up, leaving behind salt deposits. When water returned, the salt became submerged, eventually resulting in the creation of this unique underwater pool.

The key feature of brine pools is their extraordinarily high salt concentration. Some are so dense that submersibles can rest on their surface. The Hot Tub of Despair is four times saltier than the surrounding ocean, and although it lacks oxygen, it is rich in hydrogen sulfide and methane, substances that are typically harmful to marine life.

Fish and crabs that venture into the pool rarely escape. The high salt content preserves their bodies for years. However, certain organisms like bacteria, mussels, and tube worms have managed to adapt to life near the pool’s edge.

3. An Ocean Inside The Earth’s Mantle

How did water end up on Earth? While no one knows for certain, most scientists suggest that icy comets might have collided with our planet, bringing water along with them.

However, Steve Jacobsen and his team from Northwestern University propose that Earth’s water may actually have originated from within the planet itself. They provide evidence of an ocean 660 kilometers (410 mi) below the Earth’s crust, in an area of the mantle known as the transition zone. This underground ocean contains three times more water than all of Earth’s surface oceans combined.

This water resides in a mineral called ringwoodite and is gradually brought to the surface by geological processes such as earthquakes and volcanic eruptions. Not only does this underground ocean supply water to the Earth’s oceans, but scientists believe it also helps regulate the water cycle. Without it, the planet might have been entirely covered in water.

2. Unnamed Lake Under Antarctica

Lake Vostok is the largest subglacial lake in Antarctica, but this unnamed lake is the second-largest. Though scientists have not directly observed or extracted water from this lake, they determined its size and existence through satellite imagery of the ice that covers Antarctica.

Scientists observed that in certain regions, the surface ice had indentations matching those found above other known subglacial lakes. They believe that this unnamed lake takes the shape of a ribbon, stretching 100 kilometers (60 mi) long and 10 kilometers (6 mi) wide.

The lake is fed by multiple channels, some of which extend over 1,000 kilometers (600 mi). Two of these channels may even be carrying water from the lake toward the ocean. Researchers are eager to drill into the lake in the near future to investigate whether it harbors unique life forms that are not found anywhere else on Earth.

1. Lake Vostok

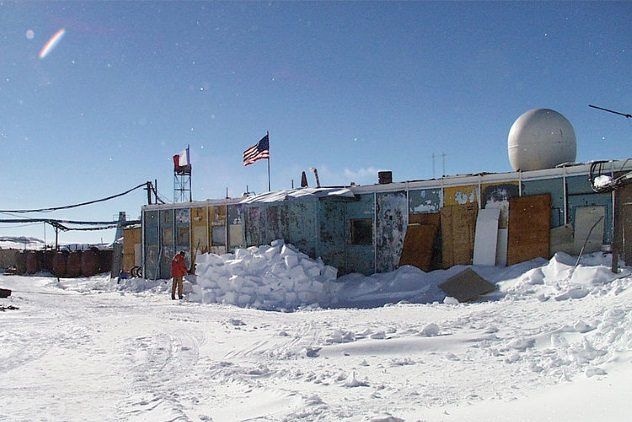

In 1990, Russian scientists drilling for ice cores at the Vostok Station in Antarctica stumbled upon a hidden lake beneath their station. This discovery led to the naming of the lake as Lake Vostok, though some prefer the name Lake East. It stretches 240 kilometers (150 mi) long and 50 kilometers (31 mi) wide, containing more than 5,400 cubic kilometers (1,300 mi) of water.

The exact formation of Lake Vostok remains uncertain, although the majority of scientists believe it resulted from volcanic activity that melted glaciers into water. The timing of its formation is also debated. Some experts suggest it occurred 30 million years ago, while others think it may have formed as recently as 400,000 years ago. However, one point of consensus is that the lake likely harbors unique organisms that have evolved in isolation from those found elsewhere on Earth.

In February 2012, Russian researchers successfully extracted water from Lake Vostok after drilling through 3,769 meters (12,366 ft) of ice. A year later, they announced the discovery of an unidentified bacteria in the water. However, there are concerns that the bacteria might not be native to the lake and could have been introduced by contaminated drills and freeze-resistant fluids used during the drilling process.