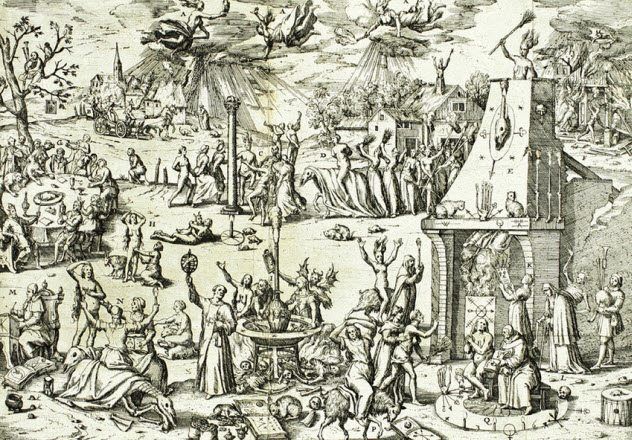

Cultures that hold a deep belief in witches are often consumed by fear and hatred toward them. Since real witches capable of casting magical spells and curses only exist in myths, this animosity is frequently aimed at ordinary women (and occasionally men). These unfortunate individuals have often found themselves caught in witch trials, leading to grim and unfortunate outcomes.

10. The Witches of Islandmagee

In September of 1710, an elderly widow of a local priest took up residence in Knowehead House in the remote area of Islandmagee, Ireland. Her stay was marked by strange occurrences, such as unseen hands throwing stones at the windows.

Everyday household items would vanish and reappear, while the bedclothes were mysteriously arranged into the form of a corpse. The widow also encountered a terrifying demonic figure who ominously warned her of her imminent death. True to its words, the widow passed away on February 21, 1711, after experiencing intense stabbing pains in her back.

The local community quickly became convinced that witches were behind the widow’s tragic demise. Suspicion grew when a young girl named Mary Dunbar discovered a peculiar apron that contained the dead widow’s bonnet, after which supernatural events began to unfold around her as well.

Mary appeared to be possessed, expelling small objects such as pins and buttons from her mouth, and even levitating above her bed. After enduring weeks of distress, Mary identified eight local women as the witches she believed were responsible for the strange occurrences, based on the images of their spirits she had witnessed.

The local clergy, along with Edward Clements, the mayor of nearby Carrickfergus (who was also an ancestor of Samuel Clemens, better known as Mark Twain), launched an investigation. Despite their pleas of innocence, the eight women were brought to trial.

There was very little concrete evidence against the accused, apart from Mary’s allegations and the reports from witnesses who described her convulsions. Nevertheless, the so-called “witches” were sentenced to a year of imprisonment in a grim and filthy prison (likely because the judge was reluctant to execute witches, especially those who, according to Mary, could apparently visit him in his dreams).

The story of the Islandmagee witches has become one of the eerier tales in the local folklore. While contemporary historians believe the women were innocent, it’s important to recognize that their sentences have never truly been rescinded. In the eyes of history, they remain witches.

9. The Great Scottish Witch Hunt of 1661–62

Scotland's largest witch hunt spread rapidly, beginning in the small towns near Edinburgh, where over 200 individuals were accused of witchcraft in less than nine months. The panic soon spread throughout the rest of the country.

By the end of 1662, a total of 660 individuals had been accused. Reports on how many of them were actually executed vary. There is concrete evidence of 65 executions (and one suicide), but some estimates suggest that as many as 450 people were killed, though this estimate spans the years 1660–1663.

Historians typically attribute the sudden and brutal witch hunt to the conclusion of English rule in the region. English judges had been reluctant to prosecute suspected Scottish witches. Once the English were no longer in control, the Scots quickly began working through their accumulated list of eccentric old women. Local church officials also took advantage of the situation, seeing it as an opportunity to reassert their influence now that the English had departed.

The end of the Great Scottish Witch Hunt is much simpler to explain. The secular authorities simply grew weary of the witch panic. Some accused witches were acquitted, a few of the more fervent witch-prickers were arrested, and no further trials were authorized. Just like that, the most infamous witch hunt Scotland had ever seen came to an abrupt halt.

8. The Doruchowo Trials

Many people overlook the fact that the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth was once a formidable European superpower. At its peak during the 16th and 17th centuries, it stood as one of the largest and most powerful early modern states on the Continent, with remarkably progressive attitudes toward religion and democracy.

This makes it all the more shocking that the Commonwealth became embroiled in one of the final mass witch trials in Europe. The Doruchowo Trials in 1775 saw the officials of Doruchowo attempt to try and execute 14 alleged witches from the nearby village of Glabowo. Even a century earlier, such a mass trial and execution would have been unimaginable in countries like England.

Curiously, this was also considered unacceptable in Doruchowo. The Commonwealth’s central parliament, the Sejm, had already prohibited village judges from handling witch trials under penalty of death in 1745. When this didn’t prove sufficient, the highest court in the land also banned town judges from conducting witch trials in 1768.

However, the officials of Doruchowo appeared to have a particular animosity toward witches, prompting their campaign against witchcraft (and law) seven years after the bans. This incident proved to be the final straw for the Sejm. Upon learning of the Doruchowo trials, they swiftly outlawed all witchcraft trials across the entire country. This effectively ended the witch trials in Poland. After Doruchowo, no further witch prosecutions appear in the country’s official records.

7. The Trier Witch Trials

The Trier Witch Trials in Germany (1582–1594) were a significant case of mass persecution in the archbishopric of Trier. The region had endured years of bad weather and failed harvests. Once the public’s suspicions focused on witches, the ruling elite openly fueled and encouraged the hysteria.

The trials were mainly led by Peter Binsfeld, a bishop who became a notorious witch hunter. Binsfeld operated under the authority of Prince-Archbishop Johann von Schonenburg.

Binsfeld and his associates didn’t solely target older women, as was typical in many witch hunts. Even influential individuals were not immune. When Trier’s deputy governor, Judge Dr. Dietrich Flade, tried to stop the witch-burning frenzy, he was tortured into confessing and burned at the stake in 1589.

Other notable figures met a similar end. For more than a decade, the Trier region was caught in a relentless witch-hunting fervor, sentencing people to death left and right. Meanwhile, notaries and executioners profited from the misery of others. By the end of the trials, at least 368 people had been burned at the stake.

Cornelius Loos was one of the rare individuals to avoid the horrific fate of the witch trials. A scholar who vocally opposed the witch hunts, Loos wrote a book expressing his views. However, the manuscript was seized, and Loos was thrown into prison.

In 1593, Loos managed to present such a compelling retraction of his views that the authorities eventually granted him a pardon. Later, Loos moved to Brussels, where he once again found himself imprisoned for his anti–witch hunt stance. He was a man who never gave up.

6. Northampton Witch Trials

The 1612 Northampton Witch Trials began like many others in that time period: with the nobility accusing common women of witchcraft. The primary accuser was Elizabeth Belcher, who had a personal vendetta against a young woman named Joan Browne.

Elizabeth began asserting that the young woman had cast a curse on her. When Elizabeth fell ill soon after, it provided all the evidence she needed to bring the matter to court. Her brother, William Avery, supported the accusations, claiming he had tried to enter the Browne cottage to break the curse, but was stopped by an invisible force.

Joan Browne, her elderly mother Agnes, and four other individuals were arrested for witchcraft and sentenced to hang. There was little chance for them, as the idea of 'innocent until proven guilty' did not exist at the time. In those days, being brought to court meant you were presumed guilty.

The tale goes that before their execution, William Avery was permitted to enter the women’s cells and beat Agnes Browne to a bloody pulp, because it was believed that spilling a witch's blood could break her curses.

That same year, Northampton also executed a man named Arthur Bill, who was accused of 'bewitching' a woman to death, along with some cattle. Arthur was thought to be from a family with witchcraft ties, so suspicion had already surrounded him as being aligned with dark forces.

The accusations tore the entire family apart. Despite Arthur's pleas of innocence, his father 'renounced' witchcraft and testified against him. Arthur's mother, fearing she too would be hanged, tragically took her own life by slitting her throat.

5. The Flowing Wells School Witch

In 1969, Flowing Wells High School in Tucson, Arizona, became the center of one of the most bizarre witch hunt cases in history. A folklore lecturer from a nearby university gave a presentation, describing the typical traits of traditional witches: blonde hair, blue or green eyes, a widow’s peak, a pointy left ear, and a preference for wearing a color known as 'devil’s green.'

This description happened to closely match Ann Stewart, a tenured teacher at the school. Naturally, the students began to joke about it. Stewart decided to play along with their fun, and when asked if she was truly a witch, her response was simple: 'What do you think?'

This turned out to be a misstep. The rumors quickly spread. Initially, Stewart enjoyed her newfound reputation. She fueled the gossip by suggesting to her literature students that they explore astrology and even dressed as a witch for a folklore lesson at another teacher’s request.

Despite her lighthearted approach and never explicitly calling herself a witch, the school district didn’t find her behavior amusing. In 1971, she was dismissed for 'passing herself off as a witch and teaching witchcraft to students.'

In an unexpected turn of events, Stewart took this particular witch trial to court herself. The judge ruled in her favor and decreed that she should be immediately reinstated. As a result, this witch hunt ended on a rare positive note for the 'witch,' who managed to retain both her position and her reputation.

However, Stewart is well aware that things could have turned out very differently in the past. 'If this were 18th-century Salem, I surely would have been burned at the stake by now,' she reflects on the ordeal.

4. Trial Of The Bideford Three

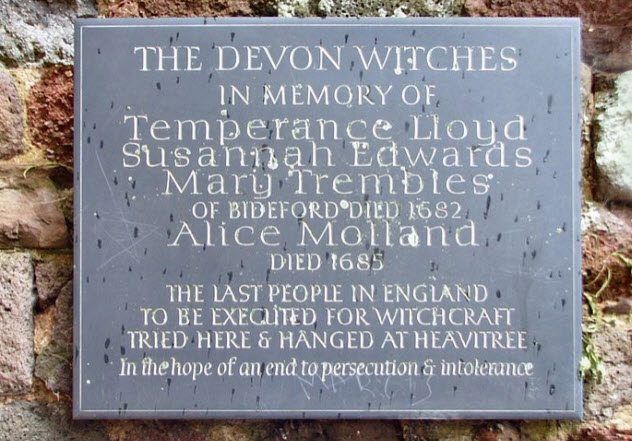

In 1682, three women from Bideford in Devon entered history in a way that they likely would have preferred to avoid. They became the last people in England to be hanged for witchcraft.

The true actions of Temperance Lloyd, Mary Trembles, and Susannah Edwards remain unknown. They were accused of making local women Grace Thomas and Grace Barnes ill and conspiring to take their lives.

Temperance Lloyd allegedly confessed to having dealings with 'the black man,' a folkloric representation of the Devil. Despite this, all three women maintained their innocence during the trial. Their pleas were in vain, and the 'Bideford witches' were hanged at Heavitree just outside the city.

Though the Bideford witches have long since passed, their case continues to resonate today. Modern British witches have adopted their plight as their own. They have erected a plaque in honor of the Bideford Three and even held protests near Exeter Castle, calling for Temperance, Susannah, and Mary to be posthumously pardoned.

3. The Northern Moravia Witch Trials

Northern Moravia, a historical region in the Czech Republic, was a perilous place for anyone suspected of witchcraft in the late 17th century. During this period, hundreds of women were executed by burning at the stake, with some trials resulting in the deaths of over 100 people.

One particular tragedy began during a church service when an altar boy noticed an elderly woman pocketing her Communion bread rather than consuming it. When a priest questioned her, she explained that she intended to give the bread to her cow to enhance its milk production.

The priest viewed this as a sign of witchcraft and reported it to a judge known for handling such cases. Sadly, the legal system of the time profited from witch trials.

As the judges and courts continued to sentence more people to burn at the stake, their earnings grew by accusing and executing more alleged witches. Their methods of finding new victims involved gathering accusations from 'concerned citizens' and, of course, resorting to the familiar tactic of torturing prisoners for confessions.

Eventually, the rising number of executions alarmed the ruling class of the region. It became clear that it was only a matter of time before they or someone close to them would fall prey to the witch hunt.

With their considerable influence, they exerted political pressure on the government to end the trials. Eventually, this succeeded, leaving the people of Northern Moravia to reflect on how they had allowed such a horrific mass killing to continue for so long.

2. Suffolk Witch Hunts

In 1645, Bury St. Edmunds, a town in Suffolk, East Anglia, became the site of England's largest single witch trial. Eighteen people were hanged in this infamous trial, orchestrated by Matthew Hopkins, who proclaimed himself the 'witchfinder general' and traveled across the region conducting witch hunts.

The Bury St. Edmunds trial was just one among many that Matthew Hopkins and his associates organized throughout Suffolk. In 1645 alone, there were 124 witch trials. While most of the accused were poor, elderly women, some men and wealthier individuals also found themselves targeted.

One of the more notable male victims was Reverend John Lowes, an 80-year-old from Brandeston. Known for his long-standing feuds and for rubbing people the wrong way, he was labeled a witch. After a brutal interrogation and a swift trial, he was hanged as one.

These horrifying events unfolded during a time of political unrest, religious zealotry, and the 1603 law that criminalized witchcraft. Opportunistic figures like Matthew Hopkins, the self-proclaimed 'witchfinder general,' saw an opportunity to profit from persecuting the vulnerable and suspicious.

1. Val Camonica Witch Trials

The inhabitants of Val Camonica, an isolated and mountainous region, likely never considered themselves witches, pagans, or heretics. Though technically under the governance of Venice, the church showed little concern for their ignorance of religious matters, leading to tragic consequences.

In 1455, a visiting foreign inquisitor was so appalled by the situation in the area that he sought the help of local authorities. They accused an 'unspecified number' of residents for 'rejecting sacraments, immolating children, and worshiping the Devil.'

While it's difficult to say whether the people of Val Camonica truly engaged in child sacrifice, their practices left such a strong impression on the Inquisition that they returned for further purges between 1505 and 1510, and again from 1518 to 1521. During these periods, about 100 people were burned as witches, often due to forced confessions, leading questions, and torture.

The inquisitors never informed Venice of their actions in Val Camonica. When the Venetian Council of Ten eventually learned about the witch hunts, they were baffled. They knew that the people there were simple, rural folk, unlikely to be involved in any demonic activity.

In response, Venice swiftly removed the chief inquisitor from the region, condemned the witch hunts, and declared that the victims of the Inquisition were martyrs.

+ The Witch Arrests Of Malawi

In the African nation of Malawi, belief in witchcraft is deeply rooted in the culture. Unfortunately, this has led many to blame their misfortunes on witches, often claiming that they are under a malevolent spell.

This widespread belief has resulted in some very unusual legal proceedings. Even in the present day, it's not uncommon for someone in Malawi to be accused of witchcraft, with individuals sometimes being imprisoned. In one month in 2010, over 80 people were sentenced to as much as six years in prison for witchcraft accusations.

This practice is not entirely lawful. In Malawi, convicting someone of witchcraft is only possible if the accused confesses to the crime, something none of the accused have done. Additionally, accusing someone of witchcraft is itself illegal. However, these cases persist because many government officials share their fellow citizens' belief in witchcraft. There have even been discussions about making 'witchcraft' a criminal offense altogether.

Yet, perhaps the ones who end up in court are the fortunate ones. By 2011, violent witch hunts were happening regularly in Malawi, targeting the most vulnerable members of society: children, the elderly, and the disabled.

Despite efforts by many officials to curb the witch hunt trend, around 75 percent of Malawi's population still holds beliefs in witchcraft. Surprisingly, Malawi's continued obsession with witchcraft isn't a lingering superstition from the past. Rather, it's viewed as a strange modern-day phenomenon linked to the region's ongoing economic and social struggles.