Renowned for its somber ambiance, New Orleans has grappled with yellow fever epidemics, a significant crime rate, and frequent hurricane threats, contributing to one of the highest mortality rates in U.S. history.

The city's above-ground tombs are iconic landmarks, yet few understand their functionality or historical significance. How did these structures come to be? Why do they remain in use, and how are they utilized today? Beyond their architectural intrigue, the rituals, customs, and traditions associated with these tombs have captivated visitors for decades.

Here’s a brief overview of how these tombs function, their historical roots, and the cultural practices that set them apart.

10. Underground Burials Proved Ineffective

Approximately 15 cemeteries in New Orleans feature above-ground tombs, a practice largely influenced by the city’s distinctive geographical setting.

Founded in 1718, New Orleans was established on an elevated riverbank adjacent to the Mississippi River. Annual flooding of the river deposited sediment, forming natural levees. The city now rests atop one of these well-drained levees.

Early settlers quickly realized the mistake of burying their dead in this elevated terrain. During floods, rising water tables would force coffins to the surface, causing them to break apart and scatter remains across the city streets.

Many of the city’s early inhabitants hailed from France and Spain, regions already accustomed to above-ground burials. This suggests that the practice wasn’t solely due to New Orleans being below sea level.

9. Yellow Fever Led to the Creation of Numerous Cemeteries

In the 18th and 19th centuries, the United States faced numerous outbreaks of yellow fever. This illness was not native to the region; it was brought over by ships from the Caribbean. Prior to 1822, cities as far north as Boston experienced outbreaks, but after that year, the disease was mostly confined to the southern areas. Port cities were especially vulnerable, and sometimes the disease traveled inland via the Mississippi River. Key cities affected included New Orleans, Mobile, Savannah, and Charleston.

Documentation of yellow fever fatalities started in 1817 and ceased in 1905 with the development of a vaccine. In that timeframe, the disease claimed over 41,000 lives. To handle the high death toll, many cemeteries were established specifically for victims of this mosquito-borne illness. St. Louis Cemetery #2 was dedicated in 1823 for this purpose, and St. Louis Cemetery #3 followed in 1853 after a devastating outbreak killed more than 8,000 people in just three months.

8. Burials Below Ground Were Once Prohibited

In 1803, the city enacted a law requiring all burials to be conducted above ground. This measure aimed to prevent bodies from being displaced by flooding and potentially spreading disease. At the time, it was widely believed that yellow fever was caused by miasma, or 'bad air,' emanating from decomposing bodies.

Today, below-ground burials are both legal and common in New Orleans. This change became possible after the introduction of a pumping system in 1914, designed by Albert Wood, which effectively drained the city. This allowed for below-ground burials, particularly for those with religious obligations. The city is home to numerous Jewish and Protestant cemeteries, while the Catholic Church owns 13 of the 43 cemeteries. Many above-ground tombs were traditionally owned by Roman Catholic families, and Protestants adopted similar burial practices out of necessity.

The installation of pumps significantly reduced the mosquito population by preventing floodwaters from stagnating after storms. Although yellow fever had been eradicated by a vaccine, malaria remained prevalent. These pumps also improved access to clean drinking water, enhancing the overall health and longevity of New Orleans residents. Albert Wood's success with these pumps led to their installation in global locations such as Amsterdam, China, and India. Despite their continued use in New Orleans, the pumps have yielded inconsistent results due to inadequate maintenance.

7. A Historic Cemetery Lies Beneath the French Quarter

Between 1723 and 1800, the deceased were buried outside the city limits, as the French Quarter was much smaller than it is today. The St. Peter Cemetery served as the city's first official burial ground. After Spain took control of Louisiana in 1762, the growing population and high mortality rates necessitated a new cemetery by the 1780s.

The St. Peter Street Cemetery was established in the 1700s outside the city's main area after the original burial site near the Mississippi River was found to damage the levee. The earlier cemetery became overwhelmed with bodies, and during heavy rains, corpses would float, turning the area into a grim, swampy mass. Residents also disposed of dead animals and waste there, transforming the site into a foul cesspool. By 1800, the original Catholic cemetery was closed, paved over, and built upon, fading into obscurity.

Even today, caskets are occasionally discovered. In 2011, Vincent Marcello found fifteen coffins while constructing a pool for his apartment complex, now locally referred to as the 'pool of souls.' The tightly packed caskets, each weighing between 600 and 800 pounds (272–363 kilograms), highlight the city's dire conditions during that era.

Remarkably, the uncovered bodies were all identified as being of African or Native American origin. This discovery highlights the diverse burial practices of old New Orleans and underscores the city's rich multicultural heritage. Estimates suggest that between 8,000 and 12,000 individuals are buried beneath this part of the French Quarter, bounded by N. Rampart, St. Peter, St. Ann, and Dauphine Streets.

6. Above-Ground Tombs in New Orleans Accommodate Multiple Individuals

While many Americans view above-ground tombs as a New Orleans innovation, they were actually common in French and Spanish cities long before their adoption in the U.S. The Spanish introduced these tombs during their colonial rule. Most tombs in New Orleans are family-owned and can house numerous individuals, functioning as slow-burning furnaces due to the region's climate.

A body is placed on a shelf within the tomb for a 'year and a day,' aligning with the Judeo-Christian belief of 'ashes to ashes, dust to dust.' After this period, the remains are either moved to the back of the tomb or relocated to a lower section. The high humidity and heat in the area naturally cremate the bodies over 50 to 60 years. These tombs can hold multiple generations, sometimes accommodating up to 60 or more individuals.

5. Bodies Are Frequently Interred Within Walls

In New Orleans, bodies are even interred within cemetery walls. This practice emerged as a cost-effective and space-saving solution to prevent corpses from being displaced by flooding. Such tombs were particularly common during the peak years of yellow fever outbreaks. Additionally, these wall tombs were sometimes utilized as 'rental tombs' for temporary burials.

When two family members passed away within the same 'year and a day' period—a frequent occurrence during yellow fever epidemics—the second deceased would be placed in a wall vault. After the required period, the remains would be transferred to the family tomb's lower section. These wall vaults are often reused by families and can hold as many as ten individuals over time.

4. Above-Ground Tombs Trace Their Origins to Roman Practices

Wall vaults in New Orleans draw inspiration from Roman Columbaria, which housed cremated remains. While Roman Columbaria were typically underground chambers carved from tufa rock and designed to hold thousands of remains, New Orleans' wall vaults are above ground and less ornate. Despite these differences, both reflect remarkable human ingenuity in burial practices.

3. Funeral Processions Often Feature Musical Accompaniment

Second Lines, also known as Jazz Funerals, are a unique cultural tradition that originated in New Orleans and remain exclusive to the city in the United States. These processions, often organized by benevolent societies, feature a solemn musical accompaniment as part of the funeral service.

In 1875, the 'Société d’Economie et d’Assistance Mutuelle,' a black benevolent society, officially designated brass band music as the standard for these processions. Over time, the somber dirge evolved into lively, upbeat tunes, and by 1883, these musical parades became a staple for the society’s annual events. Today, they are integral to both funeral ceremonies and citywide celebrations.

New Orleans’ vibrant music, fashion, and parade culture can be traced back to these early processions. They are a regular feature of life in the Crescent City, where death and life are deeply intertwined. The city’s deceased are honored and celebrated in a way that is unmatched, embodying the timeless cycle of 'ashes to ashes, dust to dust.'

2. Families Are Responsible for Cleaning and Maintaining the Tombs

In the early Catholic Church, saints were individually honored on specific days. However, as the number of saints grew, this practice became impractical. In the seventh century, Pope Boniface IV established All Saints’ Day to collectively honor all saints. Although earlier observances existed, they were not widely recognized. Initially celebrated on May 13, Pope Gregory III moved the observance to November 1 in the eighth century.

The inaugural All Saints’ Day in New Orleans took place in 1742 during the rededication of the old St. Peter Cemetery. Today, families visit their ancestral tombs to clean them and offer gifts such as flowers, photographs, food, and even alcohol. While the holiday is observed in many Catholic nations, nowhere in the United States is it celebrated with the same vibrancy as in New Orleans.

1. Society Tombs Provided Care in Life and Death

Certain minority groups lacked the resources to afford private tombs, leading to the formation of Benevolent Societies. These organizations offered medical care, hosted community events, and ensured a dignified resting place for their members. The first such group, the Perseverance and Mutual Aid Association, was established in 1783 by newly freed African individuals. Later, immigrant communities, religious orders, and less affluent French and Spanish residents also formed similar societies.

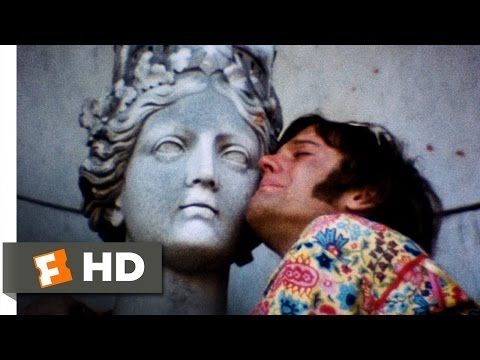

Once widespread across the Western world, Benevolent Societies remain active in New Orleans. The Italian Benevolent Society, located in St. Louis Cemetery #1, is among the most renowned. It was famously used as a filming location for the 1969 cult classic Easy Rider without the archdiocese’s permission. This marked the last Hollywood production filmed in the cemetery, with the 1965 movie Cincinnati Kid being the only other to feature the historic site.

The controversial scene in Easy Rider features a surreal blend of sexual imagery set against the backdrop of St. Louis Cemetery’s classical tombs. Peter Fonda, the film’s producer and star, is seen embracing a statue on the Italian Benevolent Society tomb, tearfully questioning, 'Why did you leave me?' and 'How could you do this to me?' The scene was filmed under the influence of LSD, adding to its chaotic and unconventional nature.

Shortly after the movie's release, the archdiocese enacted a regulation prohibiting all filming within St. Louis Cemetery #1, except for educational or religious projects. As a result, visitors are now restricted from recording videos inside the cemetery.