The Tsar Bomba, the most massive and potent nuclear device ever constructed, is depicted in a photograph from the Russian Atomic Weapon Museum in Sarov. This historic explosion occurred in the Novaya Zemlya archipelago in October 1961. TASS/Getty Images

The Tsar Bomba, the most massive and potent nuclear device ever constructed, is depicted in a photograph from the Russian Atomic Weapon Museum in Sarov. This historic explosion occurred in the Novaya Zemlya archipelago in October 1961. TASS/Getty ImagesOn October 30, 1961, a modified Soviet Tu-95 bomber headed towards Novaya Zemlya, a secluded group of islands in the Arctic Ocean. This location was a common site for the Soviet Union's nuclear experiments. A smaller aircraft, equipped with a movie camera and devices to measure air samples and radioactive fallout, accompanied the bomber.

This was no ordinary nuclear test. Beneath the bomber hung a thermonuclear bomb of such immense size that it couldn't be housed within the aircraft's standard bomb bay. The bomb, cylindrical in shape, measured 26 feet (8 meters) in length and had a staggering weight of nearly 59,525 pounds (27 metric tons).

Officially designated as izdeliye 602 ("item 602"), the nuclear bomb is more famously known by its nickname, Tsar Bomba — a title that signifies its dominance as the emperor of all nuclear weapons.

The name was well-deserved. The Tsar Bomba's explosive force is estimated at approximately 57 megatons, making it around 1,500 times more powerful than the combined impact of the atomic bombs dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki in World War II.

On that fateful day in 1961, the bomb was deployed using a parachute to slow its fall, allowing the bomber, its crew, and accompanying observer planes enough time to retreat to a safe distance.

When the colossal bomb finally exploded at an altitude of roughly 13,000 feet (4 kilometers), the resulting blast was so immense that it obliterated everything within a 22-mile (35-kilometer) radius and produced a mushroom cloud that soared nearly 200,000 feet (60 kilometers) into the sky.

In Soviet villages located 100 miles (160 kilometers) from the explosion site, wooden houses were completely demolished, while brick and stone buildings sustained significant damage.

After decades of obscurity, the Tsar Bomba regained attention in August 2020 when Rosatom, Russia's state nuclear energy corporation, shared a historic video on YouTube. The footage captured an aerial perspective of the explosion and the massive mushroom cloud it generated.

A Soviet cameraman who filmed the event recounted that the bomb produced "an intense flash across the horizon, followed by a delayed, muffled, and thunderous impact, as though the Earth itself had been annihilated." The explosion's shockwave was so forceful that it caused the aircraft carrying the bomb to plummet 3,281 feet (1 kilometer) instantly, though the pilot managed to regain control and safely return to base.

The Soviet Union Builds the Tsar Bomba

The Tsar Bomba test symbolized the intensifying rivalry between the Soviet Union and the United States during the Cold War's peak. Following a tense June 1961 meeting in Vienna between Soviet Premier Nikita Khrushchev and U.S. President John F. Kennedy, Khrushchev sought to demonstrate Soviet military strength by resuming nuclear tests, breaking the unofficial pause both nations had observed since the late 1950s.

The revival of nuclear testing provided Soviet scientists with an opportunity to experiment with their concept of constructing a colossal hydrogen bomb, one that dwarfed the most potent weapons in the U.S. arsenal, including atomic bombs.

In the grim rationale of total nuclear conflict, possessing a high-yield hydrogen bomb held theoretical merit. During that era, long-range missiles were still in their early stages, and the Soviet Union lacked a substantial fleet of strategic bombers, as noted by Nikolai Sokov, a Vienna-based senior fellow at the James Martin Center for Nonproliferation Studies at the Middlebury Institute of International Studies in Monterey, California. In contrast, the U.S. possessed a diverse array of aircraft capable of launching attacks from bases near Soviet borders.

"Therefore, if you can only deliver one, two, or three bombs, they should be exceptionally powerful," Sokov elaborated in an email.

However, Soviet scientists took this concept to an extreme. Initially, they designed a 100-megaton weapon with significant radiation output, but scaled it down to slightly over half that power after the Soviet leadership raised concerns about the radioactive fallout from such a detonation.

"Consequently, the fallout was minimal — far less than anticipated," Sokov stated. "However, the shockwave was incredibly intense, circling the globe three times."

Despite this, Japanese officials recorded the highest levels of radiation in rainwater ever observed, along with an "invisible cloud of radioactive ash" that drifted eastward across the Pacific, passing over Canada and the Great Lakes region of the U.S. American scientists, however, assured the public that the majority of the radioactive fallout from the Tsar Bomba would remain in the stratosphere, gradually dissipating in radioactivity before reaching the Earth's surface.

During the Cold War, the Tsar Bomba test produced a mushroom cloud that reached an astonishing height of 40 miles (64 kilometers).

Union of Concerned Scientists

During the Cold War, the Tsar Bomba test produced a mushroom cloud that reached an astonishing height of 40 miles (64 kilometers).

Union of Concerned ScientistsToo Big to Be Afraid Of

While the Tsar Bomba captured U.S. headlines, government officials remained unimpressed by the terrifying demonstration of nuclear power. As noted by aviation journalist Tom Demerly, the U.S. had layered defenses, including radar systems, fighter jets, and anti-aircraft missiles, which would have thwarted a Soviet bomber's first-strike attempt. Additionally, the sheer size of the Tsar Bomba posed significant risks to the aircraft delivering it, with the Tu-95 crew given only a 50-50 chance of survival.

The U.S. "considered the large bomb option and ultimately rejected it," explains Robert Standish Norris, a senior fellow for nuclear policy at the Federation of American Scientists, via email. He notes that, theoretically, hydrogen bombs can be made infinitely large. "If ever deployed, [Tsar Bomba] would undoubtedly cause massive casualties. However, improving accuracy by half allows for an eightfold reduction in yield. This is the approach we adopted, and the Soviets followed suit."

"Everyone realized it was too massive to serve as a practical weapon," Pavel Podvig stated in an email. A seasoned nuclear weapons analyst with experience at the United Nations and security programs at Princeton and Stanford universities, he also manages the site Russianforces.org. "In terms of destructive efficiency, deploying multiple smaller weapons is more effective than using a single large one."

The Tsar Bomba ultimately became a grim oddity of the nuclear era. "No further devices of this type were ever constructed," Podvig noted.

Instead, the Soviet Union shifted its focus. Shortly after the Tsar Bomba test, Soviet missile engineers made a significant advancement with liquid fuel, paving the way for the development of strategic missiles that could remain launch-ready for extended periods and be concealed in fortified silos.

"By 1964-65, the Soviet Union had firmly shifted its focus to ICBMs [intercontinental ballistic missiles, capable of carrying multiple warheads to hit different targets], which made up about 60-65 percent of its strategic force until the mid-1990s, when it decreased to around 50 percent," Sokov explained. By the 1970s, only 5 percent of the Soviet nuclear arsenal consisted of aircraft-dropped bombs.

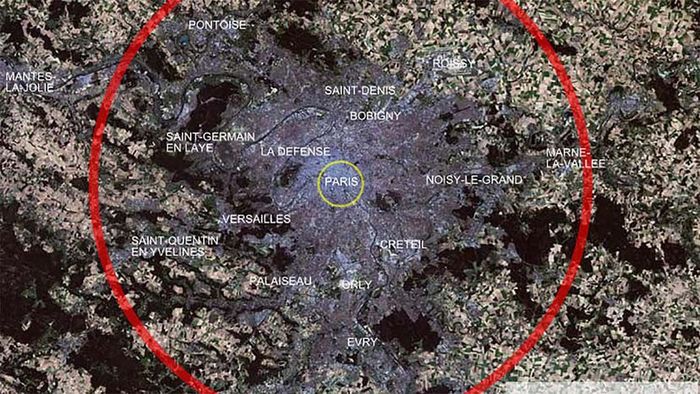

This map of Paris illustrates the area of complete devastation that would result from a Tsar Bomba detonation over the city. The red circle indicates a 22-mile (35-kilometer) radius of total destruction, while the yellow circle represents the 2.1-mile (-kilometer) fireball radius.

Wikimedia Commons (CC BY-SA 3.0)

This map of Paris illustrates the area of complete devastation that would result from a Tsar Bomba detonation over the city. The red circle indicates a 22-mile (35-kilometer) radius of total destruction, while the yellow circle represents the 2.1-mile (-kilometer) fireball radius.

Wikimedia Commons (CC BY-SA 3.0)The Soviet Union notified the U.S. in advance about their plan to test a 50-megaton nuclear bomb. In a speech delivered just a week before the explosion, U.S. Deputy Secretary of Defense Roswell Gilpatric speculated that the bomb was not aimed at intimidating the U.S. but rather at sending a message to China, the Soviet Union's uneasy ally. "This might also be the Soviet Union's response to the dissenting voice from its densely populated southern neighbor," he remarked.