Microprocessors are fundamental to every computer. Image credit: Jorg Greuel/Getty Images

Microprocessors are fundamental to every computer. Image credit: Jorg Greuel/Getty ImagesThe device you're using to view this page relies on a microprocessor to perform its functions. A microprocessor is central to any typical computer system, be it a desktop, server, or laptop. While various types of microprocessors exist, they all share a similar function and operate in essentially the same manner.

A microprocessor, often referred to as a CPU (central processing unit), is a fully integrated computation engine contained on a single chip. The Intel 4004, introduced in 1971, was the very first microprocessor. Though it lacked power, being capable of only simple arithmetic operations with 4 bits at a time, it was revolutionary because it consolidated everything into one chip. Before the 4004, computers were constructed using multiple chips or discrete components, like individually wired transistors. The 4004 also powered one of the first portable calculators.

If you’ve ever wondered what goes on inside the microprocessor of your computer or are curious about the differences between various microprocessor types, you’re in the right place. This article will walk you through how simple digital logic methods enable a computer to perform tasks, whether it’s running a game or checking the spelling of a document!

Microprocessor Evolution: Intel

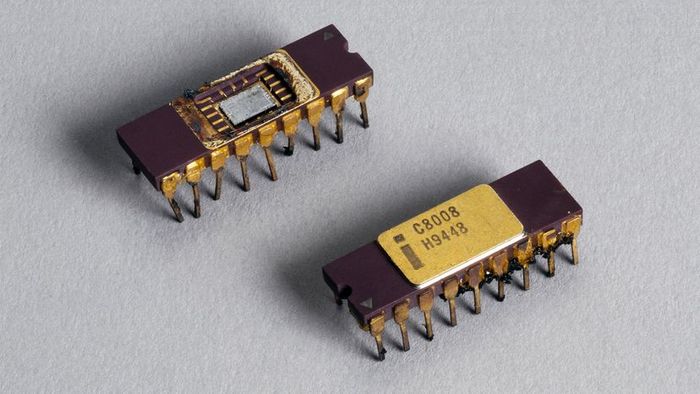

The Intel 8080, launched in 1974, was the first microprocessor powerful enough to form the foundation of a complete computer system. Science & Society Picture Library/Getty Images

The Intel 8080, launched in 1974, was the first microprocessor powerful enough to form the foundation of a complete computer system. Science & Society Picture Library/Getty ImagesThe Intel 8080, introduced in 1974, was the first microprocessor capable of building a full home computer on a single chip. In 1979, the Intel 8088 made a significant impact by being incorporated into the IBM PC, which debuted in 1982. The evolution of the PC market progressed through a series of Intel processors: from the 8088 to the 80286, 80386, 80486, Pentium, Core, and Xeon series. Each of these processors was an enhanced version of the 8088’s original design.

Since 2004, Intel has been rolling out microprocessors with multiple cores and millions more transistors. However, these newer microprocessors still adhere to the same fundamental principles as their predecessors.

An Intel Core i9 processor can house up to eight cores, each capable of executing any instruction from the original 8088 processor, but at speeds approximately 6,700 times faster! Each core can process multiple threads simultaneously, allowing for more efficient task management.

Intel's range of products has greatly expanded since the 1970s. The company continues to manufacture Pentium and Core CPUs for general computing, but higher-performance PCs and servers often use the Xeon chip. Additionally, Intel offers Celeron and Atom processors—Celeron for entry-level users and Atom for mobile devices and Internet of Things applications.

While Intel maintains a significant share of the market, it faces stiff competition. AMD challenges Intel in the PC processor market, while also excelling in graphics processor chips favored by gamers. Nvidia, well-known for its graphics chips, also produces CPUs. In 2020, Apple introduced its M-series chips, replacing the Intel processors in its Mac computers. Samsung is rumored to be developing its own proprietary processors as well. The competition is intensifying with more companies producing chips for other electronic devices, including cars and smart home products.

A chip, also known as an integrated circuit, is typically a small, thin piece of silicon that contains the transistors of a microprocessor. These chips can range in size from an inch on each side, holding tens of millions of transistors, to a few millimeters square with just thousands of transistors. Modern chips often have multiple cores, each functioning as a processor, and can be found in all kinds of electronic devices.

Microprocessor Logic

The Intel Pentium 4 was Intel’s fastest processor when it was launched in 2001. Intel/Newsmakers

The Intel Pentium 4 was Intel’s fastest processor when it was launched in 2001. Intel/NewsmakersTo comprehend the workings of a microprocessor, it helps to delve into the underlying logic used to build it. In this process, you’ll also gain insight into assembly language—the microprocessor’s native language—and explore the various techniques engineers employ to enhance processing speed.

A microprocessor carries out a set of machine instructions that tell it how to function. Based on these instructions, a microprocessor typically performs three fundamental actions:

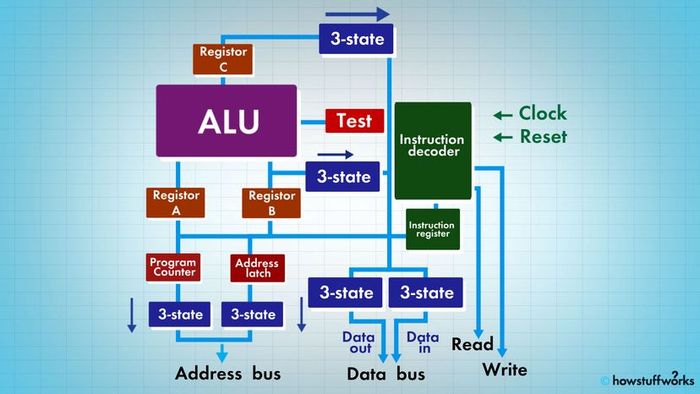

Although a microprocessor can carry out highly complex tasks, its core functions revolve around three basic operations. The following diagram illustrates a fundamental microprocessor that is capable of these three essential tasks:

The diagram presented here outlines a simple microprocessor, showcasing its components and abilities.

Mytour

The diagram presented here outlines a simple microprocessor, showcasing its components and abilities.

MytourThis microprocessor represents the most basic design, with essential features including:

- An address bus (which could be 8, 16, 32, or 64 bits wide) that communicates the address to the memory

- A data bus (which could be 8, 16, 32, or 64 bits wide) that is capable of transmitting data to memory or receiving it from memory

- An RD (read) and WR (write) line to inform the memory whether it should retrieve or store the value at the specified address

- A clock line that synchronizes the processor through clock pulses

- A reset line that sets the program counter back to zero (or another initial value) and begins the execution process anew

For this example, let's assume both the address and data buses are 8 bits wide.

Now, let's look at the components that make up this basic microprocessor:

- Registers A, B, and C are simple flip-flop-based latches. (For further understanding, see the "edge-triggered latches" section in How Boolean Logic Works.)

- The address latch functions similarly to registers A, B, and C.

- The program counter is a latch that has the added functionality of incrementing by 1 or resetting to zero when instructed.

- The ALU could be a basic 8-bit adder (refer to the section on adders in How Boolean Logic Works for more details), or it could perform more complex operations like addition, subtraction, multiplication, and division of 8-bit numbers. Let's assume it's the latter for this example.

- The test register holds the result of comparisons made by the ALU, such as determining if two numbers are equal, or if one is greater than the other. It can also store the carry bit from the adder’s final stage. These values are kept in flip-flops, and the instruction decoder uses them to guide decision-making.

- There are six blocks labeled "3-State" in the diagram, which represent tri-state buffers. These buffers can either pass a 1, a 0, or disconnect their output (like a switch that disconnects the output line). This enables multiple outputs to share a line, with only one output actively driving a 1 or 0.

- The instruction register and instruction decoder are in charge of controlling all the other components.

Although not depicted in the diagram, the instruction decoder would also manage control lines that would:

- Instruct the A register to store the value currently on the data bus

- Instruct the B register to store the value currently on the data bus

- Instruct the C register to store the value presently output by the ALU

- Instruct the program counter register to store the value currently on the data bus

- Instruct the address register to store the value currently on the data bus

- Instruct the instruction register to store the value currently on the data bus

- Instruct the program counter to increment by 1

- Instruct the program counter to reset to zero

- Activate one of the six tri-state buffers (each connected to a separate line)

- Instruct the ALU on which operation to execute

- Instruct the test register to latch the ALU’s test bits

- Activate the RD line

- Activate the WR line

The instruction decoder receives bits from the test register, the clock line, and the instruction register.

Microprocessor Memory

In the previous section, we discussed the address and data buses along with the RD and WR lines. These buses and lines typically connect to both RAM and ROM. In our microprocessor example, the address and data buses are both 8 bits wide. This allows the microprocessor to access 256 bytes of memory and transfer 8 bits at a time. Assume this simple microprocessor has 128 bytes of ROM starting at address 0 and 128 bytes of RAM starting at address 128.

ROM stands for read-only memory. A ROM chip contains a set of pre-programmed bytes that cannot be modified. The address bus tells the ROM chip which byte to retrieve and place on the data bus. When the RD line is activated, the ROM chip outputs the selected byte onto the data bus.

RAM stands for random-access memory. It holds information in bytes, which the microprocessor can either read from or write to depending on whether the RD or WR line is activated. A limitation of modern RAM chips is that they lose all data when power is lost, which is why computers require ROM.

It’s worth noting that almost all computers include some form of ROM (although it's possible to build a basic computer without RAM — some microcontrollers achieve this by embedding a small amount of RAM directly on the processor chip — but it's virtually impossible to create one without ROM). In a PC, ROM is called the BIOS (Basic Input/Output System). Upon startup, the microprocessor executes instructions stored in the BIOS, which performs tasks like testing the hardware and fetching the boot sector from the hard disk (refer to How Hard Disks Work for more details). This boot sector is another small program that gets transferred to RAM by the BIOS. The microprocessor then begins executing the boot sector instructions from RAM. The boot sector will prompt the microprocessor to load additional data from the hard disk into RAM, which the microprocessor then runs, continuing the process until the entire operating system is loaded.

Microprocessor Instructions

Even the most basic microprocessor, as shown earlier, can handle a substantial set of instructions. These instructions are encoded as bit patterns, each with a distinct meaning when loaded into the instruction register. Since humans are not adept at remembering bit patterns, a set of short words is used to represent them. This set of words is known as the assembly language of the processor. An assembler can easily convert these words into their corresponding bit patterns, and the assembler’s output is then stored in memory for the microprocessor to execute.

Here is the collection of assembly language instructions that the designer may create for the simple microprocessor in our example:

- LOADA mem - Load the contents of memory at the specified address into register A

- LOADB mem - Load the contents of memory at the specified address into register B

- CONB con - Load the constant value into register B

- SAVEB mem - Save the value in register B to the specified memory address

- SAVEC mem - Save the value in register C to the specified memory address

- ADD - Add the values of registers A and B, store the result in register C

- SUB - Subtract the value of register B from register A, store the result in register C

- MUL - Multiply the values of registers A and B, store the result in register C

- DIV - Divide the value in register A by the value in register B, store the result in register C

- COM - Compare the values in registers A and B, store the result in the test register

- JUMP addr - Jump to the specified memory address

- JEQ addr - Jump to the specified address if the comparison result is equal

- JNEQ addr - Jump to the specified address if the comparison result is not equal

- JG addr - Jump to the specified address if the value in register A is greater than that in register B

- JGE addr - Jump to the specified address if the value in register A is greater than or equal to that in register B

- JL addr - Jump to the specified address if the value in register A is less than that in register B

- JLE addr - Jump to the specified address if the value in register A is less than or equal to that in register B

- STOP - Halt program execution

If you have gone through How C Programming Works, you would recognize that this small piece of C code calculates the factorial of 5 (which is 5! = 5 × 4 × 3 × 2 × 1 = 120):

After the program has finished running, the variable f will contain the value of 5 factorial.

Assembly Language

A C compiler converts the given C code into assembly language. Assuming that in this processor, RAM begins at address 128 and ROM (which holds the assembly language program) starts at address 0, the assembly language for our basic microprocessor could look something like this:

ROM

The next question is: "How do all these instructions appear in ROM?" Every assembly language instruction needs to be represented by a binary number. To keep things simple, let's assign a unique number to each of these instructions, as shown below:

- LOADA - 1

- LOADB - 2

- CONB - 3

- SAVEB - 4

- SAVEC mem - 5

- ADD - 6

- SUB - 7

- MUL - 8

- DIV - 9

- COM - 10

- JUMP addr - 11

- JEQ addr - 12

- JNEQ addr - 13

- JG addr - 14

- JGE addr - 15

- JL addr - 16

- JLE addr - 17

- STOP - 18

The values are referred to as opcodes. In ROM, the program would appear as follows:

As you can observe, seven lines of C code were transformed into 18 lines of assembly language, which in turn became 32 bytes in ROM.

Decoding

The instruction decoder is responsible for converting each opcode into a set of signals that control the various components within the microprocessor. Let's take the ADD instruction as an example to explore its actions:

- In the first clock cycle, the primary task is to load the instruction. For this, the instruction decoder must perform the following actions:

- activate the tri-state buffer for the program counter

- enable the RD line

- activate the data-in tri-state buffer

- store the instruction in the instruction register

- During the second clock cycle, the ADD instruction is decoded, requiring minimal actions:

- set the ALU operation to addition

- store the ALU output in the C register

- In the third clock cycle, the program counter is incremented, which could theoretically overlap with the second cycle.

Each instruction can be broken down into a sequence of operations that carefully control the microprocessor components in the right order. Some instructions, like the ADD operation, may take two or three clock cycles, while others could take five or six.

Microprocessor Performance and Trends

The number of transistors directly influences processor performance. For instance, a processor like the 8088 required 15 clock cycles for a single instruction. The multiplier was especially slow, taking roughly 80 cycles just for a 16-bit multiplication. As more transistors become available, they enable more powerful multipliers that can execute in a single clock cycle.

An increased transistor count also opens the door to pipelining technology. In a pipelined design, multiple instruction executions overlap. Even though each instruction may take five cycles to execute, five instructions can be processed in parallel at different stages. This makes it seem like one instruction is completed per clock cycle.

Modern processors often feature multiple instruction decoders, each equipped with its own dedicated pipeline. This enables the handling of multiple instruction streams simultaneously, meaning more than one instruction can be completed per clock cycle. However, implementing this technique is quite intricate and requires a large number of transistors.

Trends

Processors are becoming ubiquitous, and this trend shows no signs of slowing down. Researchers have made breakthroughs in making microprocessors more adaptable, allowing devices like smart clothing to exist. There are even efforts underway to use light instead of electricity to power processors. One of the most significant developments on the horizon is the emergence of quantum computers. These machines break free from the binary system of 1s and 0s, enabling them to solve more complex problems with greater efficiency. Despite their potential, it's unlikely that quantum computers will make their way to personal desktops in the near future.

64-bit Microprocessors

Discover how 64-bit processors function and why they are capable of handling an almost limitless amount of RAM. AMD.

Discover how 64-bit processors function and why they are capable of handling an almost limitless amount of RAM. AMD.64-bit processors have been around since 1992 and have become commonplace in the 21st century. These processors feature 64-bit ALUs, 64-bit registers, 64-bit buses, and more.

The need for 64-bit processors arises from their expanded address space. While 32-bit chips are limited to a maximum of 2 GB or 4 GB of RAM, which seemed sufficient when most home computers had only 256 MB to 512 MB of RAM, modern home computers process complex data much faster. Video editing, large image manipulation, and high-end gaming all benefit from this greater computing power.

A 64-bit processor offers vast possibilities as its address space is virtually infinite for the foreseeable future, with 2^64 bytes of RAM equating to billions of gigabytes. Coupled with a 64-bit address bus and high-speed data buses, 64-bit systems also provide faster I/O speeds, enhancing performance with devices like hard drives and video cards.

For additional information on microprocessors and related subjects, explore the following links.