The Torres family likens their approach inside the globe to what pilots do in an air show. (Ringling Bros. and Barnum & Bailey)

The Torres family likens their approach inside the globe to what pilots do in an air show. (Ringling Bros. and Barnum & Bailey)The Globe of Death. Sphere of Terror. Or, for those with a weak stomach, the Globe of Steel. Call it what you will, but this stunt has been around almost as long as motorcycles have existed. A rider enters a steel sphere—constructed from tightly riveted steel bands—via a trap door. There may or may not be dramatic lighting, music, and the occasional sparkler. The rider revs the throttle, shifts his body, and races up the globe’s side. He can travel sideways, defying gravity, or even loop the loop from the North Pole to the South. For the truly daring, other riders may join in. Some even stand in the center as the bikes whirl around them, defying all laws of physics.

The genius of the Globe of Death lies in its simplicity. It requires only three elements: a large steel globe, a motorcycle, and a fearless rider. Despite its intimidating name, it’s not about death—death is strictly avoided in this stunt. Those who've experienced the g-forces of a roller coaster or taken a tight corner on a racetrack will understand the basic principle of the stunt. And yet, it still manages to feel incredibly dangerous and awe-inspiring, which is why the Globe of Death has captivated audiences for over a century. Let's dive into what makes this thrilling act work.

© 2015 Mytour, a subsidiary of Infospace LLC

© 2015 Mytour, a subsidiary of Infospace LLCThe Globe

The Torres Family performs with eight motorcycles inside a 16-foot steel sphere, where speeds can climb up to 65 miles per hour. (Ringling Bros. and Barnum & Bailey)

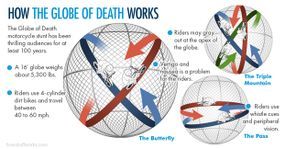

The Torres Family performs with eight motorcycles inside a 16-foot steel sphere, where speeds can climb up to 65 miles per hour. (Ringling Bros. and Barnum & Bailey)The globe is typically constructed from bands of steel (which is why it's also known as the Globe of Steel) that are riveted together. Erwin Urias has been performing inside the Globe of Death for nearly 40 years as part of the Urias Brothers act. His family continues to use a globe built by his great-grandfather, Jose Urias, back in 1912. However, that's not their only globe. Like most acts, they use various globes for different performances and stunts. The one they use most often is 16 feet (4.9 meters) in diameter and weighs 5,300 pounds (2,404 kilograms). They built it themselves as an upgrade to their grandfather's original design. "It's evolved into something more user-friendly for us," said Urias.

Today's globes are also built stronger than before — and they need to be. When motorcycles are zooming around inside the globe at around 55 miles per hour (88.5 kilometers per hour), they exert a force of to 4.5 g's on the surface. "Steel does tend to snap," Urias said, surprisingly calm for someone in his profession. But acts have learned from this tendency, as well as the different steel alloys, to make the globes they use today. Urias and his brother are certified welders and fabricators, so they've designed their globe to fit their stunts and keep them from flying into space.

Every act has its own variation of the globe, though 16 feet (4.9 meters) is the most common size. In a smaller globe, riders can go slower while still appearing faster, but the Dominguez Riders use a 17-foot (5.2-meter) globe, and Infernal Varanne boasts about using the "biggest globe ever." Split globes, which come apart in the center to form top and bottom halves, allow riders to navigate them in a unique way. In 2006, the Garcia Family built a triple-split globe — with a top, bottom, and a middle band that riders circle.

No matter the design, the globe offers something few other stunts do: it’s visible from every angle and height. Once the steel globe is rolled into place and lit up with spotlights, everyone can see everything happening inside. This visibility is what makes the act so incredible — there are no hidden parts or optical illusions. Just daredevils defying the laws of physics and testing the limits of both bikes and bodies — which we'll tackle next.

The Bike

The Torres Family has competed professionally in motocross events throughout Latin America. (Ringling Bros. and Barnum & Bailey)

The Torres Family has competed professionally in motocross events throughout Latin America. (Ringling Bros. and Barnum & Bailey)Most acts use dirt bikes in their Globe of Death performances, often from popular manufacturers like Honda or Suzuki. The bikes can't be too heavy or oversized; a lighter, more agile motorcycle performs much better in the confined space of the globe than a large touring bike with panniers and fairings. These bikes don't require high horsepower because they only reach speeds of 40 to 65 miles per hour (64.4 to 104.6 kilometers per hour), depending on the performance. However, they're not usually speed-governed, allowing the riders to control the power they need to maintain their grip on the globe’s steel surface.

Erwin Urias explains that he and his fellow riders always use customized bikes. He and his brother have become skilled mechanics to make necessary adjustments for perfecting their stunts. As Urias pointed out, "These bikes are not built to flip upside down or ride on their sides." They modify the engine, suspension, chain drive, and more. Their act uses 125-cc Yamahas, but they've enhanced the engine’s output to match that of a 150-cc bike. Higher torque is crucial when accelerating from a standstill to racing around the inside of the globe without falling off.

Many people believe there are tracks inside the globe for the motorcycles or, more strangely, that magnets are used to keep the bikes stuck to the steel. But as Urias explains — and physicists and mathematicians agree — a smaller globe simply requires less speed to make the trick work. As the rider’s speed increases, so does the centripetal force, which keeps the motorcycle’s tires pressed against the globe's walls. Friction (no magnets needed) between the tires and the sphere’s surface also plays a role. The faster the rider goes, the more friction cancels out gravity’s pull on the bike and rider. The entire act depends on centripetal force and friction, both of which rely on speed. If the rider goes too slowly, the velocity won’t be enough to overcome gravity, and both rider and bike will fall to the globe’s bottom. This is the potential "death" that’s avoided in the act.

The Rider(s)

The sound of a whistle and the roar of engines signals each rider to begin their predetermined path inside the 16-foot steel globe. (Ringling Bros. and Barnum & Bailey)

The sound of a whistle and the roar of engines signals each rider to begin their predetermined path inside the 16-foot steel globe. (Ringling Bros. and Barnum & Bailey)The final key element of the Sphere of Fear is the rider — or, more specifically, the riders. One person in the globe isn’t all that exciting, but when you add three, five, or even eight riders, it becomes a showstopper. Imagine one person standing at the bottom of the globe — or in the case of the Urias Brothers, a woman hanging by her neck from the center — while motorcycles race around her. The audience holds its breath, hoping every rider will make it safely to the bottom of the globe.

The true danger isn't in getting the motorcycles to cling to the globe’s surface. That's simply a matter of physics. The real risk comes from the intense g-forces and the blood rush felt by the riders. "When we go upside down," says Urias, "our heads are at the grayout point." In one of their stunts, Urias's wife, a professional aerialist, hangs from the center of the globe while three riders circle around her. "As she crosses the halfway point while being lifted," he explains, "we can no longer see her, and she can't see us."

Fortunately, or perhaps by design, the Globe of Death performance lasts only about 5 to 8 minutes. While there are no tracks inside the globe, the riders follow specific mental patterns. It’s never exactly the same each time, but the execution of the pattern is precise. Timing is everything, which is why riders can be seen rocking back and forth at the globe's bottom. The first few riders speed off, while the others rock, rev, and wait for the perfect moment to start their loops.

Urias stays physically fit to endure the toll that riding inside the globe takes on his body. "You need to eat well and manage your weight," he said. "If you're too heavy, the motorcycle absorbs all the impact." He also stressed that maintaining the body helps prevent injury. He does basic exercises like pull-ups and push-ups, and his son, soon to be a regular rider in the act, runs for cardiovascular fitness. These are essential for handling the g-forces and maintaining focus during the performance.