Mike "Big Bird" Bird, a civilian volunteer collaborating with official agents to monitor the U.S.-Mexico border for illegal immigrants, won't carry an LED Incapacitator. However, U.S. Border Patrol agents will be equipped with this device.

David McNew/Getty Images

Mike "Big Bird" Bird, a civilian volunteer collaborating with official agents to monitor the U.S.-Mexico border for illegal immigrants, won't carry an LED Incapacitator. However, U.S. Border Patrol agents will be equipped with this device.

David McNew/Getty ImagesMain Points

- The LED Incapacitator is a non-lethal device engineered to temporarily incapacitate individuals through high-intensity flashing lights.

- It employs rapidly shifting light patterns that overload the brain, leading to disorientation and nausea.

- Though promoted as a safer option compared to conventional weapons, the LED Incapacitator sparks ethical debates over its potential misuse and possible long-term health impacts.

A law enforcement officer stationed at a border crossing faces the task of apprehending a suspect in a vehicle without resorting to gunfire. The officer must disorient the suspect briefly to gain control. What options does the officer have?

The officer might consider using a stun gun or Taser, but this would require close proximity to the suspect, which isn't the case here. Additionally, Tasers carry the risk of triggering a heart attack in some individuals.

Another option could be directing a laser into the vehicle to distract the suspect. Lasers are effective at a distance and have been used unlawfully to disrupt airplane pilots during critical flight phases. The U.S. military has also utilized this strategy in Iraq for inspecting vehicles suspected of carrying terrorists [source: FoxNews.com]. However, lasers pose a risk of eye damage, potentially causing blindness.

A strobe light might be the officer's optimal choice. The intense, rapid flashes overwhelm the suspect's vision, causing temporary disorientation. This technique, known as strobing, isn't yet officially recognized in dictionaries.

Researchers at Intelligent Optical Systems in Torrance, Calif., have created an advanced strobe system that not only disorients suspects but also induces severe nausea. Known as the LED Incapacitator (LEDI), this device utilizes light-emitting diodes. The U.S. Department of Homeland Security has supported its development with a $1 million grant for testing this nonlethal weapon.

Intelligent Optical Systems isn't the sole player in this field. Other nonlethal technologies, like the Active Denial System (ADS), use microwave radiation to heat the water in the skin's surface layers, creating a burning sensation. Designed to avoid deep skin penetration, the ADS minimizes permanent damage. Mounted on trucks, it's ideal for crowd control but impractical for individual officers or soldiers.

The Personnel Halting and Stimulation Response (PHaSR) employs two low-power diode lasers to distract suspects without causing blindness. While effective at a distance, the PHaSR is bulkier, less portable, and more power-consuming compared to the LEDI. Both the PHaSR and LEDI remain in development and testing stages, with neither being deployed to soldiers, law enforcement, or made available to the public.

Next, we'll explore why the compact and portable LEDI induces such a strong nauseating effect.

LED Incapacitator Effects

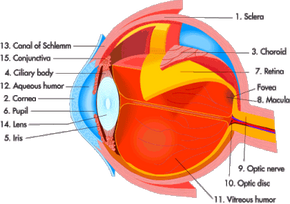

Key components of the human eye

2009 Mytour

Key components of the human eye

2009 Mytour

The LED Incapacitator (LEDI) employs intense, rapid bursts of light to confuse and overwhelm the target. While strobe lights have been used by law enforcement in the past, the LEDI stands out due to its ability to emit varying colors (red, green, and blue), spatial patterns, frequencies, and intensities. This combination temporarily blinds, disorients, and induces nausea in the subject without causing harm. The disorientation lasts several minutes, providing ample time to subdue the suspect. Its nauseating effect has even earned it the nickname "puke ray."

To understand how strobing disorients, it's essential to know how visual information is processed. The lens of the eye focuses an image onto the retina, a layer packed with light-sensitive cells called photoreceptors. Once the image is captured and converted into electrical signals, the optic nerve sends it to the brain's visual cortex for interpretation. The brain has a limited capacity to process visual information. If this information arrives faster than the brain can handle, the person becomes temporarily incapacitated. The frequency needed to overwhelm the brain ranges from 7 to 15 hertz [source: Rubtsov].

Strobing disrupts visual processing in two key ways. First, the intense brightness of the strobe creates afterimages in the brain. For example, if you stare at a bright light (avoid the sun) and then close your eyes, you'll still "see" the light's afterimage. Second, the strobe's frequency, around 15 hertz, interferes with the brain's ability to process visual data, leading to disorientation and nausea. Even after the LEDI is turned off, the nausea persists for a few minutes as the brain recovers.

Law enforcement officers don't need to aim the strobe directly at the suspect's eyes. Simply illuminating the area so that some flashes are near the suspect's eyes is sufficient [source: Rubtsov].

Now, let's explore how the LEDI operates.

Inside the Incapacitator: Not Your 1970s Disco Strobe Light

Mytour

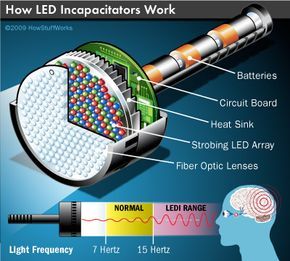

MytourThe LEDI is roughly the size of a large flashlight. Unlike traditional flashlights with a single lightbulb, reflector, and lens, this nonlethal device features an array of light-emitting diodes in multiple colors, each paired with a small lens plate.

Powered by batteries, the LEDI's circuit board manages the intensity and sequence of the light flashes. It determines which LED activates, the order of activation, and the speed of the flashes. The circuit board can be programmed with various flash patterns, allowing officers to select modes tailored to stationary or moving targets.

The lens plate, primarily constructed from fiber optics, focuses the light from each LED and aligns the beams to a narrow 5-degree target angle. Additionally, the strobe may include a range finder, similar to a digital camera's autofocus, to adjust flash intensity based on the target's distance from the device.

Current LEDI prototypes feature a sizable 4-inch (10-centimeter) head. Intelligent Optical Systems is actively working to shrink this component to resemble a standard flashlight. The long-term goal is to develop compact LEDIs that can be attached to firearms, similar to a laser sight.

Before the LEDI can be deployed to induce nausea in the public, researchers at Penn State's Institute for Non-Lethal Defense Technologies must conduct volunteer trials. Following this, the Los Angeles County Sheriff's Department plans to use the device for patrols, while the U.S. Department of Homeland Security intends to employ it for border security operations.