Pneumatic tubes are still in use today, visible at bank drive-up windows, where they efficiently send items back and forth.

Ryan McVay/Photodisc/Getty Images

Pneumatic tubes are still in use today, visible at bank drive-up windows, where they efficiently send items back and forth.

Ryan McVay/Photodisc/Getty ImagesFor those born after 1992, it may be hard to believe, but there was once a time before e-mails, cell phones, or Kindle’s digital books. Even more astonishing, in those days, documents were rapidly sent through a technology known as the pneumatic tube.

While the lack of immediate communication might make the past seem like a slow-paced era, it didn’t appear that way to the people of the time. One reason was the presence of pneumatic tubes—systems of pressurized air that moved canisters carrying documents and other objects. In a way, it was their version of the Internet, but entirely mechanical, not digital. This method of transmission was powered by compressed air and worked through an extensive network of tubes, transporting goods swiftly. [source: Library – UC Berkeley].

From the mid-to-late 19th century onward, major cities across the U.S. and other nations constructed expansive underground pneumatic tube networks, relying on them just as heavily as we depend on email today. In fact, New York City’s post office relied on pneumatic tubes to move mail until 1953, and Berlin operated a similar system until 1976 [source: Web Urbanist].

While electronic methods of communication have mostly replaced pneumatic tube transport, this technology is still useful for certain applications. In this article, we will explore how pneumatic tubes operate, their historical uses, and their current applications.

How Compressed Air Moves Objects

The intricate metal-and-glass design of pneumatic tube systems seems like the epitome of Victorian technology, resembling the kind of complex gadgets you might imagine Robert Downey Jr. experimenting with in a Sherlock Holmes film. However, the principle of pneumatics — using pressurized gas for mechanical motion — actually dates back to Hero of Alexandria, a Greek mathematician, inventor, and author from the 1st century A.D. [sources: Merriam-Webster, Britannica].

Hero of Alexandria was quite observant. He realized that wind, despite being invisible, could exert considerable force on objects. This led him to conclude that air was made up of tiny, invisible, moving "particles," which we now call molecules. He further deduced that if these molecules were compressed into a confined space or passage, they would seek to escape, pushing objects in front of them. He also realized that creating a vacuum — an empty space — would cause air molecules to rush in. Through these principles, he wrote, "many curious and astonishing kinds of motion may be discovered" [source: Woodcroft].

Hero applied his knowledge of pressurized gases to invent devices such as a rudimentary steam engine and a mechanical singing bird. However, it wasn’t until 1810 that British engineer George Medhurst published a proposal for a pneumatic tube-based rapid transport system [source: Woodcroft].

Medhurst discovered that when air was subjected to 40 pounds per square inch of pressure — just two-and-a-half times the pressure of the atmosphere at sea level — air molecules would travel at 1,500 feet (457 meters) per second, or approximately 1,000 miles (1,609 kilometers) per hour. When pushing a canister, the speed would be reduced to around 100 miles (160 kilometers) per hour, but this was considered incredibly fast for 1810 [source: Medhurst].

Unfortunately, Medhurst wasn’t as skilled in building the machinery as he was in conceptualizing it. He passed away in 1827, before he could bring his invention to life [source: Stephen and Lee].

The Air-powered Internet

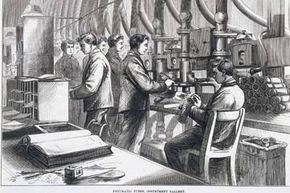

A plate from the "Illustrated London News" depicting workers using pneumatic tubes at the Central Telegraph Establishment of the General Post Office.

SSPL/Getty Images

A plate from the "Illustrated London News" depicting workers using pneumatic tubes at the Central Telegraph Establishment of the General Post Office.

SSPL/Getty ImagesIn the 1850s, Great Britain’s General Post Office took a closer look at Medhurst's concept, and by the 1860s, they hired engineer T.W. Rammel to design a vast system to move mail across London. By 1886, London's pneumatic tube network had expanded to 34 miles (54.7 kilometers) under the city, handling 32,000 messages daily. While letters didn't travel as fast as Medhurst had envisioned, reaching only 51 miles (82 kilometers) per hour, it was still far quicker than traditional horse-drawn wagons [sources: Library – UC Berkeley, Grace's Guide, U.S. Congress].

By the early 20th century, New York had installed its own pneumatic tube system, enabling cylindrical containers filled with letters and parcels to zip through underground loops at speeds of 30 miles (48 kilometers) per hour. Cities such as Boston, Chicago, Philadelphia, and St. Louis followed suit with similar systems [source: Library – UC Berkeley].

The ingenuity of pneumatic transport led some to imagine its use for more than just mail. In 1867, inventor Alfred Beach constructed and briefly operated a 300-foot (91-meter) pneumatic tube subway beneath a section of Broadway in Manhattan, hoping air-powered trains would catch on. Later, in 1913, Waldemar Kaempffert, editor of Scientific American, proposed the idea of preparing meals in central kitchens and sending them to homes via pneumatic tube. He even asked, "If a letter can be shot through a pneumatic tube from New York to Brooklyn, why not a five-course dinner?" [source: Massachusetts Institute of Technology].

As people in the Edwardian era grew increasingly excited about pneumatic technology, World War I quickly dampened their enthusiasm. The U.S. Post Office temporarily halted pneumatic mail services, citing the high fuel consumption needed to power the air compressors. After the war, the service was revived, but only in New York and Boston.

Due to growing Congressional regulations and the increasing demand for mail delivery, private companies stopped bidding to expand the systems. Ultimately, the existing systems could not keep up with the volume of mail. As a result, the Post Office shifted to investing in mail trucks, which offered the advantage of transporting mail over longer distances and handling larger packages. In 1953, U.S. Postmaster General Arthur Summerfield ended the pneumatic tube mail system permanently and ordered its dismantling [source: Cohen].

Modern Uses of Pneumatic Tubes

Pneumatic tube transport never fully vanished. As long as paper documents and photographs remained in use, it was an effective means of moving information within large buildings. For instance, the U.S. Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) constructed an extensive pneumatic tube network in its headquarters in Langley, Virginia, in the 1950s, which transmitted 7,500 documents daily across seven floors. The system remained in use until 1989, when the widespread adoption of e-mail rendered the tubes obsolete [source: CIA].

In the 1970s, businesses began using more robust pneumatic tube systems to transport materials like machine parts and even gravel within factories [source: New Scientist]. These systems are still widely used in various industries for such purposes [source: Air Link International]. Additionally, banks continue to employ pneumatic tube systems at their drive-up windows, allowing customers to make deposits or withdrawals without leaving their vehicles [source: Farber].

Recently, hospitals have turned to pneumatic tube systems to quickly transport tissue and blood samples from distant labs, far faster than any human could manage on foot. For example, Stanford University’s hospital boasts 4 miles (6.4 kilometers) of pneumatic tubes, handling 7,000 specimens daily. These 19th-century tubes are now paired with 21st-century technology, featuring digital monitoring systems that let hospital staff track the canisters' progress on computer screens [source: Wykes].