The Venus de Milo remains a perennial highlight at the Louvre Museum in Paris, France. Todd Gipstein/Getty Images

The Venus de Milo remains a perennial highlight at the Louvre Museum in Paris, France. Todd Gipstein/Getty ImagesA symbol of intrigue in the art world, the Venus de Milo has captivated audiences and historians since Louis XVIII gifted her to the Louvre in 1821. Despite her fame, her origins and the mystery of her missing arms continue to puzzle many.

The marble statue widely known as Venus de Milo likely depicts two figures unrelated to Venus, the Roman goddess of love and beauty. Scholars believe it represents either Aphrodite, her Greek equivalent, or Amphitrite, the sea goddess and Poseidon's wife. Discovered in 1820 on Melos (modern-day Milos) and later gifted to Louis XVIII, her true identity and the story behind her missing arms remain enigmatic.

"When the Louvre obtained the statue in 1820, the British Museum had recently acquired the Elgin Marbles (1816), widely credited to the fifth-century B.C.E. sculptor Pheidias, celebrated by both ancient and modern scholars as the pinnacle of Greek sculpture," explains Andrew Stewart, Nicholas C. Petris Professor of Greek Studies Emeritus at UC Berkeley, via email. "Additionally, the Louvre and French art faced significant setbacks when Napoleon's looted art collection was repatriated between 1815 and 1818. The museum lost iconic pieces like the Vatican Laocoön and Florence's Venus de Medici. Thus, the Venus de Milo (more accurately, 'Aphrodite,' given her Greek origin) became a symbol of national pride and a divine gift."

However, the statue's distinctive features made it challenging for experts to pinpoint her origins. "Given her later stylistic elements yet classical essence, she was initially credited to Praxiteles, the renowned fourth-century B.C.E. sculptor and master of the female nude, particularly the love-goddess Aphrodite. A base discovered with her, signed by [Alex]andros of Magnesia on the Meander (a city established only in the third century B.C.E.), was promptly and conveniently misplaced."

Stewart notes that German archaeologist Adolf Furtwängler identified Venus de Milo as a Greek neoclassical statue rather than a classical one, a revelation that emerged in the late 19th century. Furtwängler recognized her drapery as distinctly Hellenistic, likely crafted in the second century B.C.E. Despite this, the statue is often associated with an earlier era. "She remains a masterpiece of the [classical] genre, partly due to the rarity of originals matching her size, preservation, and quality," Stewart adds.

Although the Louvre website refers to the statue as 'shrouded in mystery,' certain aspects of her original appearance are known. For instance, she once adorned metal jewelry, including a bracelet, earrings, and a headband, evidenced by fixation holes on her body. The marble she's carved from may have featured polychromy that has since faded. Additionally, she originally had arms, though they were never recovered.

A detailed close-up of the Venus de Milo at the Louvre Museum reveals dowel holes in the right arm, which likely once held the top of the statue's draped clothing. Francois LOCHON/Gamma-Rapho/Getty Images

A detailed close-up of the Venus de Milo at the Louvre Museum reveals dowel holes in the right arm, which likely once held the top of the statue's draped clothing. Francois LOCHON/Gamma-Rapho/Getty Images"The right arm is broken off: its hand originally clutched the top of her draped garment," Stewart explains. "The bust, legs, left arm, foot, base, and the herm [an ancient bearded head of a god mounted on a square stone pillar] inserted into the base were each carved separately and attached using iron dowels set in lead, a common practice of the time."

Stewart suggests that during the end of antiquity, a period marking the transition from the Greco-Roman era to the Middle Ages, someone removed Venus' arms to extract and reuse the metal dowels. "In my view, she likely held an apple in her extended left hand, resting it on the herm," he says. "A similar arm was discovered in a nearby niche and is depicted in a 19th-century drawing at the Louvre. The apple would symbolize both her personal attribute (her prize from the 'Judgment of Paris') and a play on the island's name, as the Greek word for apple is μήλον (mēlon), and apples are prominently featured on Hellenistic coins from Melos."

The 'Judgment of Paris' is a pivotal Greek myth central to Venus' significance, depicting a contest among three goddesses — Aphrodite, Hera, and Athena — for a golden apple inscribed 'To the Fairest.' In his book, 'Art in the Hellenistic World: An Introduction,' Stewart explores the Venus de Milo's symbolic connections. He writes, "Dedicated to the gods of the gymnasium where she was found, she would have represented the bonds of affection (erôs) among the Melians who frequented the space. Additionally, Greeks interpreted the 'Judgment of Paris' as symbolizing a man's three primary life choices: war (Athena), politics (Hera), or love (Aphrodite)." Stewart notes that as Romans were heavily involved in war and politics, the third option — love, marriage, and domestic life — grew increasingly appealing. Venus' multifaceted symbolism, he adds, "would have fostered a sense of community among the gymnasium's patrons, fulfilling both local religious devotion and the era's desire for connection."

Elizabeth Wayland Barber, professor emerita of archaeology and linguistics at Occidental College and author of 'Women's Work: The First 20,000 Years Women, Cloth, and Society in Early Times,' argues that Venus' missing arms were likely engaged in a significant domestic activity. "While researching the origins and evolution of textiles in the Eastern Hemisphere (evidence now shows humans spinning thread or yarn over 50,000 years ago and weaving 25,000 years ago), I found extensive evidence that women predominantly handled textile-related tasks," Barber explains via email. "The Venus de Milo's posture aligns with the spinning position common in that era — a task that consumed much of women's time, as they spun thread whenever possible."

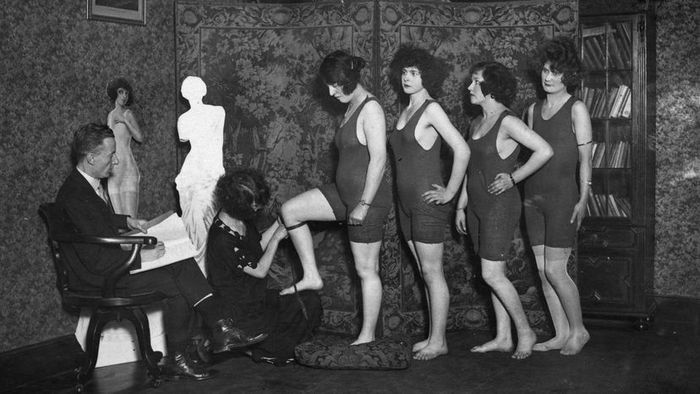

In 1924, contestants at a West End Cinema in London were measured to determine if any matched the proportions of the Venus de Milo, an antiquated and, thankfully, obsolete standard of feminine beauty. Firmin/Topical Press Agency/Getty Images

In 1924, contestants at a West End Cinema in London were measured to determine if any matched the proportions of the Venus de Milo, an antiquated and, thankfully, obsolete standard of feminine beauty. Firmin/Topical Press Agency/Getty ImagesBarber notes that while the statue's arms are missing, the muscular definition in her shoulders and upper back indicates they were likely raised in the precise posture needed for spinning. Her gaze is fixed on the exact spot one would focus on while spinning. "Additionally, Aphrodite (also known as Venus) was regarded by the Greeks as the goddess of spinning and procreation," Barber explains. "These roles are closely connected, both through the umbilical cord tied to a newborn and the shared process of transforming a shapeless mass into something extraordinary, as if by magic." Barber's book even includes an illustration of the Venus de Milo reimagined as spinning.

While experts debate the original purpose of the Venus de Milo, many agree she remains one of the most captivating and enigmatic creations of the Hellenistic Period. As Jonathan Jones of The Guardian wrote in 2015, "The Venus de Milo is an accidental surrealist masterpiece. Her armless form makes her eerily surreal. She is both flawless and flawed, beautiful yet fragmented — a body as a ruin. This sense of mysterious incompleteness has turned an ancient artifact into a modern icon."

Mytour may earn a small commission from affiliate links in this article.

Many art enthusiasts are unaware of the true scale of the Venus de Milo until they stand before her: she towers at an impressive 6 feet 8 inches (2 meters 20 centimeters).