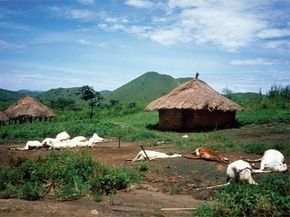

Cattle lay lifeless around the settlements in Nyos village on September 3, 1986, nearly two weeks after the deadly explosion at the lake.

Photo courtesy of the U.S. Geological Survey

Cattle lay lifeless around the settlements in Nyos village on September 3, 1986, nearly two weeks after the deadly explosion at the lake.

Photo courtesy of the U.S. Geological SurveyMain Takeaways

- On August 21, 1986, Lake Nyos in Cameroon unleashed a massive CO2 cloud, suffocating over 1,700 people and countless animals by replacing the oxygen in the air.

- Researchers found that CO2 had been gradually seeping into the lake, eventually erupting in a catastrophic release triggered by a rockslide.

- In an effort to prevent future tragedies, engineers installed pipes to continually vent the lake, greatly lowering the chances of another CO2 eruption, though the region remains a potential danger zone.

For years, Lake Nyos had been peaceful and serene. To farmers and nomadic herders in the West African country of Cameroon, it was known as a vast, calm, and blue lake.

On the evening of August 21, 1986, farmers living near the lake heard a rumbling sound. Simultaneously, a foamy spray shot up from the lake, and a dense white cloud formed above the water. The cloud grew to a height of 328 feet (100 meters) and drifted across the land. As the farmers approached the scene, they lost consciousness.

The thick cloud descended into a valley, directing it into nearby villages. People in its path suddenly collapsed, whether at home, on the road, or in the fields, losing consciousness or dying almost instantly. In Nyos and Kam, the first villages affected, all but four people on high ground perished.

The valley split open, and the cloud continued its path, claiming lives as far as 15.5 miles (25 kilometers) from the lake. Over the following days, people from surrounding areas ventured into the valley, only to find the bodies of both humans and cattle scattered across the ground.

By August 23, the cloud had largely dissipated, and silence fell over the area. After being unconscious for as long as 36 hours, some survivors awoke to the grim reality that their family members, neighbors, and livestock had all perished.

The lake itself had undergone a transformation. It became shallower, with plants and debris floating on the surface, and its once-vibrant blue color had turned into a murky rust hue. What was the mysterious and deadly force behind the events at Nyos? Find out next.

Examining the Nyos Disaster

Over a week after the eruption, Lake Nyos lost its vibrant blue color, now appearing brown. The surge of water that followed the toxic gas cloud's emergence left visible damage to the surrounding vegetation.

Photo courtesy of the U.S. Geological Survey

Over a week after the eruption, Lake Nyos lost its vibrant blue color, now appearing brown. The surge of water that followed the toxic gas cloud's emergence left visible damage to the surrounding vegetation.

Photo courtesy of the U.S. Geological SurveyScientists quickly discovered that the cloud was composed of carbon dioxide (CO2), which explained its dense nature, as CO2 is heavier than air. The cloud was a mixture of CO2 and air. CO2 directly caused death by preventing consciousness and respiration. When the CO2 concentration was below 15 percent, individuals lost consciousness and later revived. However, inhaling CO2 concentrations above 15 percent caused people to stop breathing within minutes, leading to death.

There was disagreement among scientists regarding the cause of the CO2 release from the lake—up to a third of a cubic mile of it. One theory suggested that a volcanic eruption released CO2 and caused the lake to erupt. Another theory proposed that CO2 was gradually accumulating and being stored in the lake, only to be released in a massive, deadly burst when the lake exploded.

"While the two scientific factions disagreed, they all concurred that CO2 was the cause of death, and that people would be safer on higher ground," said William Evans, a geochemist from the U.S. Geological Survey who studied the disaster. The Cameroonian government took the necessary steps based on this advice.

Evans and his team set up CO2 monitors along the lakeshore. These monitors were connected to sirens that would go off if the CO2 levels in the air became too high. The alarms served as a warning, signaling people to head to higher ground.

Over the years, scientists came to a conclusion about the origin of the CO2. By measuring the gas at the bottom of Lake Nyos, they discovered a layer rich in CO2, with gas levels rising over time, indicating that CO2 was gradually leaking into the lake from beneath.

Scientists searched for signs of a volcanic eruption, such as sulfur and chloride in the lake. They also placed seismometers around the water to record small earthquakes that might follow a volcanic event. According to Evans, "It was the quietest area that the British Geological Survey had ever monitored." This led to the abandonment of the volcanic eruption theory. The CO2 was seeping into the lake from below.

The scientists theorized that CO2 had been trapped at the bottom of Lake Nyos for a long period, held in place by 682 feet (208 meters) of water. On the day of the eruption, something triggered the gas release, most likely a rockslide from one of the lake's walls. As the rocks sank to the lake's bottom, they displaced the gas, which then bubbled up to the surface.

If this seems like an unusual event to you, continue reading to learn about another lake that erupted in a strikingly similar manner just two years earlier.

The Exploding Lakes: Lake Monoun and Others

Could Lake Kivu be the next candidate for an explosive event? The lake, pictured here at dusk on October 3, 2006, in Goma, Democratic Republic of Congo, is fed by CO2 leaking from the magma below and is also incredibly deep.

Could Lake Kivu be the next candidate for an explosive event? The lake, pictured here at dusk on October 3, 2006, in Goma, Democratic Republic of Congo, is fed by CO2 leaking from the magma below and is also incredibly deep.Almost two years prior, on the evening of August 15, 1984, residents about 62 miles (100 kilometers) southeast of Nyos heard similar rumblings near a different lake. This was Lake Monoun, the site of an earlier explosion. At around 11:30 p.m., CO2 burst from the lake, flooding into a nearby valley and down a road. People from the village of Njindoun, on their way to work before dawn, walked into the cloud and collapsed, losing their lives.

By around 10:30 a.m., the wind had carried the cloud away. A doctor and a police officer arrived at the scene to discover that most of the 37 victims had fallen along a short stretch of road, including one man found slumped over his motorcycle [source: Sigurdsson].

Initially, the Cameroonian government suspected the explosion was either a terrorist attack or the result of someone dumping chemicals into the lake. However, the more traditional villagers in Njindoun believed in a local legend that evil spirits would periodically leave the lake and kill those nearby. "These legends probably originated from previous gas bursts," explains Evans.

Lake Kivu, located between Rwanda and the Congo in the African Rift Valley, is a serious concern for potential eruption. It is more than twice as deep as Lake Nyos and has the capacity to store a larger amount of gas. Methane is produced by bacteria in the lake, and carbon dioxide is seeping in from the magma beneath it. Sediment studies indicate the lake could have erupted between 7,000 and 8,000 years ago, says Varekamp. With over 2 million people living nearby, the gas pressure in the lake is constantly monitored. As Varekamp warns, "If that ever were to go, that would be a natural disaster on a scale we haven't seen, except for the tsunamis in 2004."

Another lake of concern is Lake Quilotoa in Ecuador, which is rich in CO2, deep, and located in a tropical climate. Some researchers regard it as a potential counterpart to Lake Nyos, as noted by Varekamp.

You might be curious whether any lake is capable of exploding. Could your backyard pond be in danger? Let’s revisit some historical lakes to explore this question.

Recipe for a Killer Lake

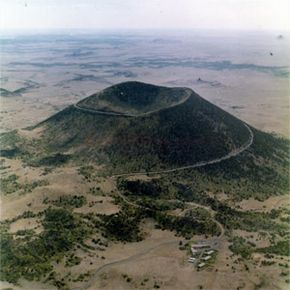

Capulin Volcano National Monument in New Mexico features Capulin Mountain, a massive cinder cone that erupted thousands of years ago. The mountain stands 1,000 feet (305 meters) above its base. Photo courtesy of R.D. Miller/U.S. Geological Survey.

Capulin Volcano National Monument in New Mexico features Capulin Mountain, a massive cinder cone that erupted thousands of years ago. The mountain stands 1,000 feet (305 meters) above its base. Photo courtesy of R.D. Miller/U.S. Geological Survey.Exploding lakes are an uncommon phenomenon, and the histories of Lakes Nyos and Monoun help explain why. In Cameroon, there are weak areas in the Earth's crust where magma, or liquid rock, rises from the Earth's mantle. The magma ascends quickly and vertically, creating a pathway to the surface. If it breaks through, the magma may erupt and send rocks flying, forming a cinder cone volcano.

If the magma encounters wet rock during its ascent, it can cause an explosion, resulting in the formation of a crater in the ground. Over 18,000 years ago, such an eruption created the crater at Lake Monoun [source: Sigurdsson]. A similar explosion occurred a few hundred years ago, leading to the formation of Nyos [source: Kling]. Water filled these craters, transforming them into lakes.

At the base of each lake, the remnants of the tube where magma first emerged remain. If you trace this tube for about 3 to 6 miles (5 to 10 kilometers) down, you will eventually reach the magma. The immense pressure at that depth forces one of the most common gases in molten rock, CO2, to escape. This gas travels up the tube and into the lake. Research has found over 100 locations in Cameroon where CO2 leaks in substantial, but non-threatening, amounts from the ground, according to Evans.

Several conditions, beyond just CO2, need to align for a lake to explode. First, the lake must be deep. With a minimal amount of water weighing down the gas at the bottom, it only takes a slight disturbance—such as wind—to release the gas. In deep lakes, the water above acts as a cork in a champagne bottle. Each 10 meters (33 feet) of water exerts 1 atmosphere of pressure, so in a 100-meter (328-foot) deep lake, 10 atmospheres of pressure keep the gas at the bottom in check, says Evans. Wind alone can't disturb it.

Second, the climate needs to remain stable throughout the year, which is why exploding lakes tend to be found in tropical regions. For example, Lake Superior in the U.S. builds up gas from decaying matter until the seasons change. Every fall, the surface cools and becomes denser, sinking to the bottom. This causes the gas-laden water at the bottom to rise, and the lake turns over or exhales—a process that most lakes undergo at least once annually, according to Varekamp. In regions with consistent year-round temperatures, the layers of the lake maintain their stability. Third, a trigger such as a landslide, earthquake, or excessive gas accumulation is necessary to destabilize the gas layer.

Cameroon possesses all the essential factors for lakes to erupt: magma pushing CO2 into deep water bodies, a tropical climate, and an event that triggers it all.

Degassing Lakes with Large Tubes

Following the eruption of Lake Nyos, a global team convened to discuss methods for venting both lakes and preventing similar future calamities. They considered bombing the lakes to release the gas, but scientists feared that such an explosion could breach one of the lake's walls, leading to a catastrophic flood. "That would be a disaster in itself," says Evans. By November 1986, French scientists had proposed an alternative solution: a pipe.

"The pipe solution prevailed due to its simplicity and the relatively low risk involved," says Evans. "It would allow for controlled gas removal."

The installation of pipes took longer than anticipated due to limited funding and insufficient road access to Nyos. "When we left Cameroon in 1986, we were confident we had completed thorough scientific work, proposed a viable solution, and assured that aid organizations would arrive the following week to begin piping the gas out. It was an eye-opening moment for all of us, realizing just how long such processes can take," recalls Evans.

The initial pipe was installed in Lake Nyos in 2001. A French engineering team lowered a 6-inch (15-centimeter) plastic tube 666 feet (203 meters) into the lake to reach the gas layer [source: Halbwachs]. Once again, bubbles erupted like champagne from an uncorked bottle, but this time it was not a deadly surprise.

Currently, Lake Nyos is about 80 percent degassed compared to the state it was in following the 1986 eruption, says Evans. "The lake is safer now than it was in 2000, but it still remains dangerous." He adds that a significant energy input, such as a major earthquake or a landslide, could potentially trigger another eruption.

Another concern is the fragile wall of Nyos. "That natural dam could fail at any time," says Evans. "If it were to suddenly collapse, the upper 40 meters [131 feet] of the lake would drain in a massive flood, releasing the pressure on the gas trapped in the deep waters. This could result in both a flood and a gas release." Evans emphasizes the need to pipe out the gas immediately and repair the wall. Plans for two additional pipes are in place, with the first potentially being installed in spring 2009.

Lake Monoun has three pipes: one installed in 2003 and two more in 2006. "An eruption is unlikely there now, since the lake is almost entirely degassed," says Evans. "Monoun would now be a lovely place to live."

So, the next time you detect the sulfurous gas while your local lake turns over, consider it the lake 'breathing out' — and be thankful it’s not a burp.