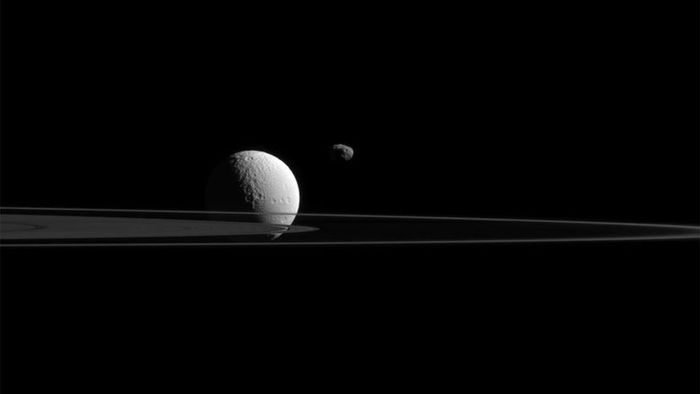

Saturn is home to 62 known moons. Among them are Tethys, the larger moon in the front, and Janus, the smaller one in the back. Could these moons have their own moons orbiting them? (NASA/JPL-Caltech/Space Science Institute)

Saturn is home to 62 known moons. Among them are Tethys, the larger moon in the front, and Janus, the smaller one in the back. Could these moons have their own moons orbiting them? (NASA/JPL-Caltech/Space Science Institute)If planets can have moons, is it possible for these moons to host their own moons? Some moons in our solar system, such as Jupiter's Ganymede and Saturn's Titan, are even larger than Mercury, the smallest of the eight recognized planets by the International Astronomical Union.

Despite their intriguing potential, astronomers have yet to find a 'moonmoon' — a moon orbiting another moon, whether within our solar system or beyond. (Interestingly, they recently discovered what could be the first exomoon, a Neptune-sized object that seems to be orbiting a massive exoplanet, Kepler-1625b.) Could moonmoons truly exist, or would the planet's intense gravitational forces prevent them from maintaining their orbit and lead to their destruction?

In a preliminary version of a scientific paper shared on the arXiv pre-print server, astronomers Juna A. Kollmeier from Carnegie Observatories and Sean N. Raymond from the Laboratoire d'Astrophysique de Bordeaux in France suggest that moonmoons — or 'submoons' as they refer to them — could indeed exist, but only under very specific conditions.

Researchers concluded that moonmoons with a diameter of 10 kilometers (6.2 miles) or more could only exist around moons that are at least 100 times larger, and orbit their planets in wide-separation orbits. They identified four moons in our solar system — Saturn's Titan and Iapetus, Jupiter's Callisto, and Earth's moon — that meet these criteria, along with a possible exomoon orbiting Kepler-1625b.

However, as Raymond noted in the October 10, 2018 edition of NewScientist, even if moonmoons are feasible, a piece of rock would have to be ejected with the correct velocity to orbit the moon instead of the planet or a nearby star. Additionally, if a moon undergoes orbital changes over time, as Earth's moon has, the moonmoon likely wouldn't stay with it. This could explain why no moonmoons have been discovered so far.