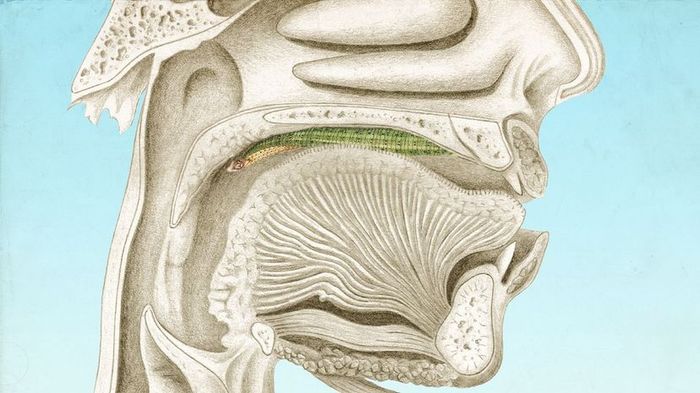

Even in the modern day, people continue to arrive at hospitals globally with leeches lodged in their throats. DEA Picture Library/Matt Wimsatt/Getty Images.

Even in the modern day, people continue to arrive at hospitals globally with leeches lodged in their throats. DEA Picture Library/Matt Wimsatt/Getty Images.In 1895, Surgeon-Lieutenant T. A. Granger of the British Indian Army wrote a letter to the British Medical Journal about a chilling case of parasite infestation he encountered at his post. While stationed at a fort in the North-West Provinces of India, Granger received a report from an officer describing a local man with a leech inside his throat.

Initially skeptical, Granger agreed to meet the patient. He found an elderly Pashtun man with a gray beard, who, upon seeing Granger, immediately spat out a large amount of thick, blackened blood—likely to prove the seriousness of his condition.

With the aid of interpreters, Granger questioned the elderly man about his condition. The man explained that 11 days earlier, while drinking from a rainwater tank, something got stuck in his throat. When he tried to cough it out, he couldn't, and then it started moving. He struggled to swallow, felt as if he might choke on the writhing obstruction, and began vomiting and spitting up blood repeatedly.

When Granger examined the old man's throat, he initially removed a blood clot but found no visible parasites. If there was one, it must have been deeper. So, Granger used a pair of long polypus forceps—essentially tweezers with scissor handles—and carefully reached into the lower pharynx, near the esophagus. There, he felt something moving and, with the forceps, grasped the squirming obstruction, pulling it out with considerable force.

It was, indeed, a leech, measuring between 2.5 and 3 inches (6.4 and 7.6 centimeters) in length, with a shape reminiscent of the .303-inch bullets used in British infantry's Lee-Metford rifles. This slimy, wriggling 'rifle cartridge' had been feeding on the man's blood for 11 days inside his pharynx.

Granger's letter to the BMJ doesn’t mention what happened to the old man after the leech was removed, but one would imagine that after such a terrifying ordeal, the worst part of his experience was surely behind him.

Granger’s report is not an isolated case. He himself heard of similar incidents in nearby towns, and this phenomenon is not exclusive to 19th-century India. The medical world has specific terms like 'leech endoparasitism' or 'internal hirudiniasis' to describe this condition. While these terms may sound unsettling, even today, in the 21st century, people still present at hospitals around the world with leeches lodged inside their throats.

Introducing the Leech

Technically, a leech is a type of worm from the phylum Annelida and the subclass Hirudinea, which gives rise to the term 'hirudiniasis'—the condition of being parasitized by a leech. Leeches are characterized by segmented bodies (think of 'rings,' like those of an earthworm) and suckers at both ends: a larger one at the rear, used for movement and anchoring, and a smaller one at the front that holds the jaws and mouth. While some leeches feed on detritus or hunt other creatures, the type most familiar to us is the blood-sucking parasite that attaches to a larger host and steadily drains blood, often until the leech expands to approximately 10 times its original size. In nature, leeches will feed on various hosts, including mammals, fish, and amphibians.

When a leech bites, it makes a Y-shaped incision with its three curved jaws, which are lined with tiny, serrated teeth, resembling little circular saws. It then uses a muscular sucking action to draw blood. The saliva of a leech contains a mix of substances, including hirudin, a polypeptide that prevents blood from clotting. While leeches are typically external parasites that feed on the blood of their host through the skin, they will also feed from internal surfaces when given the chance, such as the nasopharynx, larynx, vagina, bladder, and anus.

Humans share a unique and longstanding relationship with leeches that stands out among all parasitic interactions. The use of leeches has been widespread in the history of medicine, even lending the European medicinal leech, Hirudo medicinalis, its modern name. In certain historical periods, leeches were so widely used for bloodletting that collecting wild leeches became a profitable enterprise.

If the thought of a leech feeding on your skin already disgusts you, the idea of a leech inside your body might seem even worse. However, during the leech craze, enthusiasts didn’t stop at the outer skin. They allowed leeches into various bodily orifices, even internal cavities, often with the aid of medical devices. In a 2011 article on the history of leeching technology, Robert G.W. Kirk and Neil Pemberton describe how '[t]he opening of the interior of the body often required the physical alteration of the leech, for example the attachment of thread to prevent the loss of the leech within, or the supplementation of the leech with mechanical tools to enable the passage of the creature into locations such as the anus where it was now recommended as a means to treat problematic prostates.'

Leeches have occasionally proven useful in modern medicine, though their applications remain somewhat controversial. For example, they have been employed to help ensure that veins function properly and do not become overfilled or distended after microsurgery.

Recent Cases

Medical journals still report rare instances of accidental internal hirudiniasis, including cases of leeches in the throat.

In 2002, doctors reported in the journal Pediatric Pulmonology a case involving a 6-year-old boy from Syria who had difficulty breathing. His mother explained that the child had been coughing up blood, and a month earlier, a village doctor had misdiagnosed him with asthma, prescribing corticosteroids and bronchodilators. The real cause was discovered when doctors removed a 7-centimeter (2.8-inch) leech from the boy’s airway during surgery. It was later found that the child had been drinking from a leech-infested stream in rural northern Syria. Once the leech was removed, the boy's symptoms disappeared.

In 2009, another case was reported in the European Journal of Pediatrics involving an 11-year-old boy from central Iran. He arrived at a rural health center with blood in his mouth and a sore throat that had persisted for two weeks. Despite being treated with antibiotics, his condition did not improve. Upon examination, doctors discovered a black, circular mass about 2 by 3 centimeters (0.8 by 1.2 inches) stuck to the back of his throat. They used lidocaine spray for pain relief and then removed the leech with blunt forceps. The boy had been swimming in a local lake, and after the leech was removed, blood continued to ooze from the wound for about an hour. Fortunately, the boy recovered fully afterward.

In 2013, Dr. Demeke Mekonnen published an article in the Ethiopian Journal of Health Science detailing the case of a 7-year-old boy in Ethiopia who presented with blood-stained saliva and difficulty breathing. Attempts were made to treat him with a traditional remedy made of tobacco leaves and flax seed, but with no success. Mekonnen's report indicated that the boy had been exposed to an unprotected spring water source that was also used for watering animals. Laryngoscopy revealed a foreign object lodged at the top of the trachea. The child was anesthetized, and a leech was removed using forceps. Following the extraction, the boy fully recovered.

If You Have a Leech in Your Throat

While laryngeal and pharyngeal leech infestations are uncommon these days, especially in developed countries with easy access to clean water, they can still occur. Symptoms of a leech in the throat may include difficulty swallowing, sore throat, vomiting blood, coughing up blood, a sensation of a foreign body in the throat, melena (dark, sticky stools from swallowed blood), shortness of breath, and stridor (raspy or harsh breathing).

If you suspect a leech is in your throat, don’t panic. Seek medical attention promptly. As demonstrated by the cases above, while pharyngeal or laryngeal hirudiniasis can be serious, it is not necessarily life-threatening, especially if the parasite is obstructing the airway. If the doctor is familiar with the condition and has blunt forceps available, the prognosis is generally good. However, the best course of action is prevention. These cases highlight the importance of drinking only from clean, purified water sources and avoiding swimming in waters that may harbor leeches.

When William Wordsworth wrote, "What have I? shall I dare to tell? / A comfortless and hidden well," it’s likely he was speaking metaphorically about a wellspring of romantic feelings, not about a literal water source that's uncomfortable due to being contaminated with leeches.