In 2020, there were 19,379 deaths caused by gun violence in the U.S., according to the Gun Violence Archive. Explore more images of firearms. Wikimedia Commons (CC BY 2.0)

In 2020, there were 19,379 deaths caused by gun violence in the U.S., according to the Gun Violence Archive. Explore more images of firearms. Wikimedia Commons (CC BY 2.0)Over 10.6 million firearms, including pistols, revolvers, shotguns, rifles, and other weapons, were produced in the United States in 2020 [source: Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives]. In 2019, guns were involved in 14,414 homicides [source: CDC]. A 2017 study by the Geneva-based Small Arms Survey revealed that U.S. civilians owned nearly 40% of the world's firearms, with about 121 firearms for every 100 U.S. residents. The survey also found that of the 857 million civilian-held firearms globally, 393 million are in the U.S., more than the combined total of the next 25 countries.

Given the high number of firearms, the odds of being shot might seem alarming. In 2015, Americans had a 1 in 315 chance of dying from a gunshot, based on population and gun violence statistics [source: Mosher and Gould]. So, if someone nearby pulls out a weapon, what should you do?

Ed Sizemore, a lead instructor at the Federal Law Enforcement Training Center's Firearms Division, recommends that for an average bystander, the best option is to retreat. If that's not feasible, he advises taking cover. Hiding behind something that can absorb the impact of the bullets is a smart choice, as is dropping to the ground, which reduces the size of your target for the shooter.

Sizemore instructs his law enforcement students to face the threat directly. Shooters usually aim for the most accessible target — the torso. Since police officers are equipped with body armor, they have the most protection on both their front and back. However, Sizemore stresses that this advice isn't applicable to civilians.

According to Sizemore, there's no definitive best spot to be shot. Ballistics — the study of projectiles like bullets — is unpredictable. He notes, "People get shot in fatal areas and survive, while others get shot in less critical areas and die." However, he suggests that the most agonizing place to be shot is the pelvis, as the nerve bundle there distributes pain rapidly throughout the body. He also points out a medically worse area: "The brain," he says. "Hearts can be repaired. There's such a thing as an artificial heart. But as far as I know, there are no artificial brains."

However, the brain may not always be the most deadly place to be shot. A study of more than 400 patients from two level 1 trauma centers between 2000 and 2013 found that patients with gunshot wounds to the head had a 42% chance of survival [source: Muehlschlegel].

But if you ever find yourself in a situation where you must choose where to take a bullet — perhaps a choice presented by an irate loan shark — where should you choose to take it?

Top Choice for a Bullet

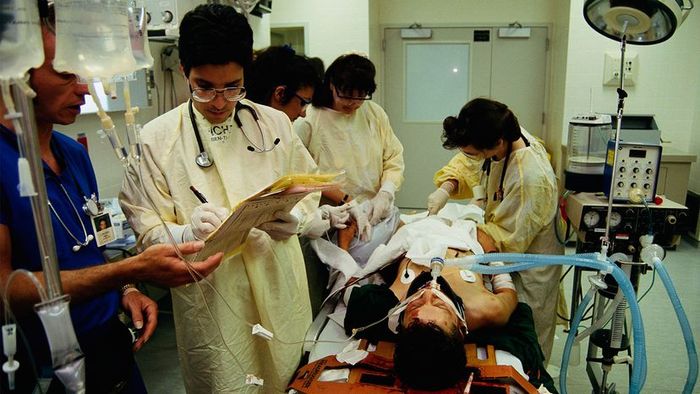

Surgeons treat a gunshot wound victim in the emergency room at Ben Taub General Hospital in Houston, Texas. Wound ballistics is the field dedicated to studying how projectiles impact bones, tissue, and organs, and the research begins when medical professionals cannot save a patient. Gregory Smith/Getty Images

Surgeons treat a gunshot wound victim in the emergency room at Ben Taub General Hospital in Houston, Texas. Wound ballistics is the field dedicated to studying how projectiles impact bones, tissue, and organs, and the research begins when medical professionals cannot save a patient. Gregory Smith/Getty ImagesAlthough there isn't a comprehensive study about the best anatomical spot to be shot, there are several possible areas. To determine where the best place to be shot might be, it’s essential to first understand the nature of bullets and the way they interact with the human body.

Wound ballistics, the study of how bullets affect tissue, bones, and organs, has led to some clear conclusions about the destructive power of projectiles. A bullet acts as a vehicle for force, and its purpose is to transfer that energy into the body, causing injuries directly or indirectly.

The severity of an injury caused by a bullet is directly related to its kinetic energy, which is determined by the bullet's weight, speed, and gravitational path. These three factors combined determine the level of damage a bullet can inflict.

When a bullet enters the body, it causes both lacerations and crushing wounds. It punctures tissue and bone, pushing or crushing anything in its path. As it moves through tissue, the bullet creates a cavity that can be up to 30 times wider than its track (the path it travels). Although the cavity quickly closes behind the bullet, the cavitation it causes can lead to damage to nearby tissues, organs, and bones through shock waves.

The nature and extent of injury from a bullet also depend on what it encounters along its path. Soft tissue transmits shock waves more easily than bone, but bones, being denser, absorb more of the bullet's force (and damage). Bones also fragment, sending shards through the body that cause additional harm as they act as projectiles themselves.

A bullet that exits the body through an exit wound typically causes less damage than one that remains inside, as the latter transfers all of its kinetic energy and inflicts maximum tissue damage. Modern bullet designs take this into account. Jacketed bullets are made to fragment after impact, dispersing their destructive energy. Hollow-point and soft bullets are crafted to expand and flatten, increasing their track width and intensifying the damage through shock waves and cavitation.

From this understanding, we can deduce the areas where you’d least want to be shot and identify the safer spots. A bullet can break bones, and bones can also trap a bullet inside the body. Therefore, areas with dense bone mass, like the ribs, should be avoided. Nerve bundles, as Ed Sizemore pointed out, should also be avoided. Most importantly, you’d want to protect your vital organs, making the torso and head areas particularly risky.

It seems like your arms and legs are the best places to take a bullet. However, both your thighs and upper arms contain critical arteries — the femoral and brachial arteries. If either is severed, the resulting blood loss can lead to death within minutes. Therefore, the legs and arms are not safe options.

Considering their location and distance from vital organs, your hands or feet appear to be the safest areas to take a bullet. A gunshot to the foot or hand would certainly break many bones and be excruciatingly painful, but it wouldn't be life-threatening. Even though there are numerous bones in these areas that could shatter, the fragments are less likely to travel toward vital organs like your heart. Additionally, since your hands and feet are relatively thin, a bullet is more likely to pass through without fully transferring its destructive energy. You may end up with a disability, but you'd stand a better chance of surviving the ordeal.

Editor's Note: Ed Sizemore was interviewed in 2007.

In 1822, Canadian Alexis St. Martin was accidentally shot beneath his left breast at close range. The musket ball tore away parts of his left side, exposing bone, tissue, and organs. His stomach was punctured and exposed, and the attending physician, Dr. William Beaumont, predicted that St. Martin would soon die.

Miraculously, St. Martin survived for another 66 years, though his wound never fully healed. Dr. Beaumont took advantage of the exposed stomach to study digestion, using the wound to extract digested food and better understand stomach functions, which had previously been only theorized until St. Martin's (educationally) fortunate accident [source: University of Houston].