Initially, one might assume that the expression may you live in interesting times is a kind of blessing. After all, isn’t an exciting life preferable to a dull one?

However, the most captivating eras in history are rarely the most peaceful. Tales of conflict, invasion, scarcity, deceit, and other grim occurrences often fill the pages of history. While these events may be intriguing to study later, those who endure such turbulent times typically face immense fear and suffering.

As a result, may you live in interesting times is often interpreted as more of a curse than a blessing—not a supernatural one, but certainly a way of wishing misfortune upon someone. Below, explore the intriguing (though somewhat unclear) background of this widely recognized saying.

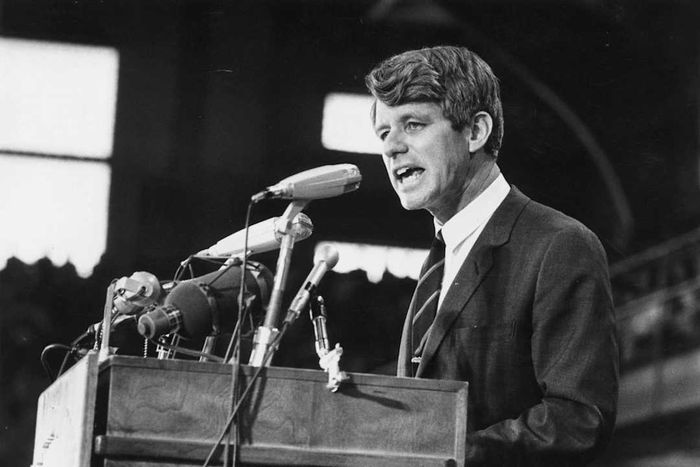

How RFK Brought the Phrase to Prominence

One of the most notable instances of this phrase being used was during Robert F. Kennedy’s Day of Affirmation speech, delivered at the University of Cape Town in June 1966.

In what is now famously known as his “Ripple of Hope” address, Kennedy highlighted the similarities between the fight against Apartheid in South Africa and the U.S. Civil Rights movement, underscoring that challenging periods often aim to achieve greater ideals of justice. RFK credited a specific saying to an ancient Chinese proverb:

“There is a Chinese curse that states, ‘May he live in interesting times.’ Whether we like it or not, we do live in interesting times. These are times filled with danger and unpredictability, yet they are also the most innovative periods in human history.”

Bobby is often credited with popularizing the phrase. | Harry Benson/GettyImages

Bobby is often credited with popularizing the phrase. | Harry Benson/GettyImagesAs the “Ripple of Hope” speech gained global recognition, it played a significant role in spreading the phrase, especially among intellectuals such as Albert Camus and Hillary Rodham Clinton, who further cemented its widespread use.

For motivational purposes, the quote certainly works well. However, RFK’s speechwriter made one error: There is no such curse or proverb in Chinese. A Chinese phrase resembling RFK’s quote can be found in the 1627 short-story collection Stories to Awaken the World. The book’s anti-war sentiment is evident in the phrase (寧為太平犬, 不做亂世人, or níng wéi tàipíng quǎn, bù zuò luànshì rén in Simplified Chinese), which translates to “it’s better to be a dog in peaceful times than a human in chaotic ones.”

Who First Used the Phrase?

While the core idea of may you live in interesting times might have been inspired by an ancient Chinese proverb, this doesn’t fully account for how the phrase evolved into a “curse,” particularly with the emphasis on “interesting” times rather than just chaotic ones. It’s likely that the version familiar to Americans stems from a mistranslation (or misinterpretation) by British diplomats in the early 20th century.

In 1936, the phrase suddenly gained traction within the British diplomatic community. In his memoir Diplomat in Peace and War, Sir Hughe Knatchbull-Hugessen, a British ambassador to China, recounts a discussion about it: “Before my departure to China in 1936, a friend mentioned to me that there is a Chinese curse—’May you live in interesting times.’ If true, our generation has undoubtedly experienced the [fulfillment] of that curse.”

That same year, Frederic R. Coudert, honorary vice president of the American Society of International Law, corresponded with diplomat Sir Austen Chamberlain, a close friend and brother of Neville Chamberlain, who would become British Prime Minister in 1937. Coudert concluded one of his letters to Sir Austen with a casual observation about how they were “living in an interesting era.”

Coudert noted that Chamberlain responded, “I was informed by one of our diplomats in China that one of the most severe Chinese curses is, ’May you live in an interesting age.’” Chamberlain also reportedly stated that “no period in history has been more uncertain than our current time.”

Don’t point the finger at Neville—his father, Joseph, was likely the true source. | General Photographic Agency/GettyImages

Don’t point the finger at Neville—his father, Joseph, was likely the true source. | General Photographic Agency/GettyImagesSome have speculated that the Chamberlain family not only popularized the phrase but may have also shaped its precise wording. Austen and Neville’s father, Joseph Chamberlain, was a prominent politician who used the exact phrase we live in interesting times in speeches between 1898 and 1901, making it likely that his sons were familiar with it.

While it’s possible the phrase stemmed from a conversation between Sir Austen and a diplomat stationed in China (who may have misinterpreted the idea behind it’s better to be a dog in a peaceful time), it’s probable that prejudiced views toward China contributed to its perception as a kind of curse.

The phrase is not a Chinese curse at all. However, attributing it to “ancient Chinese wisdom” likely added an air of mystique, making it more captivating and memorable to audiences in the mid-20th century. This enigmatic quality made it ideal for speeches—even though it was likely more of a British invention than a Chinese one.