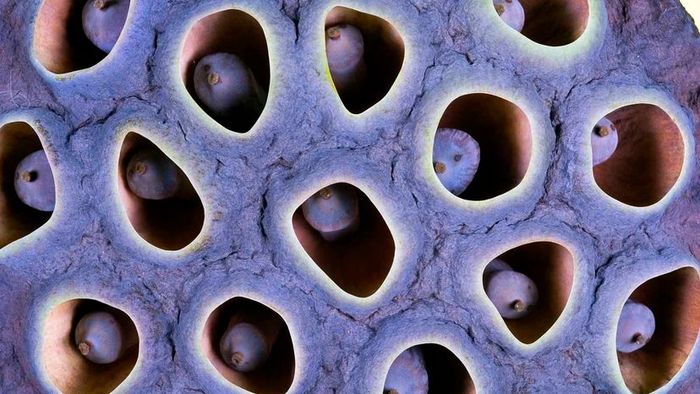

The lotus flower's seed pod is a well-known image that often evokes feelings of disgust in those suffering from trypophobia. Credit: Gail Shumway/Getty Images

The lotus flower's seed pod is a well-known image that often evokes feelings of disgust in those suffering from trypophobia. Credit: Gail Shumway/Getty ImagesImagine the sight of strawberries, honeycombs, and fluffy pancake batter. Does it remind you of a delightful summer meal, or does it evoke a sense of dread akin to a horror scene? For those with trypophobia, these images might trigger intense discomfort or anxiety.

Trypophobia refers to an aversion or revulsion toward patterns of tightly clustered holes. Individuals with this condition may feel nauseated when viewing objects like lotus seed pods or experience symptoms like sweating, panic, or sickness when encountering bubble-filled surfaces. Despite its name implying a psychological fear, there is ongoing debate about whether trypophobia should be classified as a true phobia, as it is not officially recognized in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM).

What Is Trypophobia?

"Trypophobia differs from typical phobias," explains Arnold Wilkins, a professor emeritus in psychology at the University of Essex, in an email. As a leading expert in visual stress, he notes, "There isn't a single trigger, and the reasons behind it remain unclear. It's more about a disgust response than a traditional fear-based phobia."

Unlike standard phobias, which are driven by fear, trypophobia primarily elicits feelings of disgust. Individuals with this condition often react strongly to objects like coral, lotus seed pods, or even frothy coffee bubbles—essentially anything featuring clusters of holes.

A 2018 review highlights that women are more prone to trypophobia, with common co-occurring conditions including major depressive disorder and generalized anxiety disorder. Additional symptoms may include:

- Feelings of helplessness, disgust, or fear

- Goosebumps, itching, or a crawling sensation on the skin

- Dizziness, trembling, or difficulty breathing

- Sweating, body tremors, or a rapid heartbeat

- Headaches

- Nausea or vomiting

Wilkins first encountered trypophobia unexpectedly when his colleague, Dr. Geoff Cole, shared his personal experiences with the condition, which began at age 13 during a metal shop project involving drilling small holes into a coin, an activity that made him feel nauseated.

"I was researching visual discomfort caused by images and found that certain unnatural patterns could predict this discomfort," Wilkins explains. "Dr. Geoff Cole approached me, sharing his own trypophobia. I hypothesized that trypophobic images might share statistical similarities with other unsettling visuals—and my theory was correct."

In 2013, Wilkins and Cole published a study proposing that trypophobia might stem from visual patterns resembling those of venomous creatures, triggering an evolutionary alarm in the brain. Their research revealed that approximately 16% of participants experienced trypophobic reactions.

"My fascination with trypophobia began after reading Cole and Wilkins' 2013 paper, 'The Fear of Holes,'" writes R. Nathan Pipitone, Ph.D., an assistant professor of psychology at Florida Gulf Coast University, via email. "The subject aligns with my interest in evolutionary human responses. After discussing it with a student, we initiated a research project in 2015."

In 2017, Pipitone published a study titled "Physiological responses to trypophobic images and further scale validity of the trypophobia questionnaire," which reinforced Wilkins and Cole's findings. The paper noted that trypophobic images elicit negative reactions and share spatial frequency traits with dangerous animals, as highlighted by Cole and Wilkins (2013).

"What struck me most was the diverse reactions people have to trypophobic images," Pipitone notes. "Our visual perceptions are deeply rooted, and there's usually consensus on what we find appealing or unsettling. However, while those with severe trypophobia experience intense discomfort, others might find the same images oddly pleasing."

Trypophobia is a serious condition. Experts believe it may stem from an evolutionary mechanism to steer clear of infectious diseases.

Micha Pawlitzki/Getty Images

Trypophobia is a serious condition. Experts believe it may stem from an evolutionary mechanism to steer clear of infectious diseases.

Micha Pawlitzki/Getty ImagesBut Why Patterns of Holes?

In 2017, researchers at the University of Kent proposed a new theory to explain the aversion to clustered holes. They suggested that this reaction is an evolutionary defense mechanism against stimuli resembling signs of parasites or infectious diseases, such as measles, rubella, smallpox, ticks, and scabies, which often present with clustered, round shapes.

Although this reaction is typically a natural, adaptive response, individuals with trypophobia exhibit an "excessive and generalized version" of this instinct.

Regardless of the root cause of trypophobia, Pipitone emphasizes that the diverse reactions to it highlight human individuality and underscore the importance of empathy and understanding toward others' experiences.

"Just because you don't find these images disturbing doesn't mean others share your perspective," he explains. "Since most people don't have trypophobia, they might dismiss the reactions of those who do. In today's world, it's crucial to recognize that others' realities may differ from ours. This understanding could benefit us in numerous ways."

Treating Trypophobia

While there is no specific treatment for trypophobia, general phobia therapies may help alleviate its symptoms for those affected.

- Exposure therapy gradually introduces individuals to their fears, aiming to reduce their anxiety over time.

- Cognitive behavioral therapy helps patients collaborate with a therapist to modify thought patterns and behaviors contributing to trypophobia.

- Relaxation methods, such as deep breathing exercises, can alleviate feelings of disgust, fear, or anxiety triggered by trypophobia.

- Medications prescribed for depression or anxiety may also help manage the symptoms.

Other common triggers for trypophobia include Bubble Wrap, insect eyes, pomegranates, and sea sponges.