Santa Claus’s peculiar traditions invite curiosity, from his preference for chimneys as entry points to his choice of coal as a punishment. His iconic ho ho ho also sparks questions, like: What does it signify?

Most people believe that when Santa lets out his triple ho, he’s expressing joy through laughter. However, the origins of ho ho ho as a representation of laughter—and how it became Santa’s signature phrase—are more intricate than they seem.

The Element of Surprise

The Oxford English Dictionary notes that a double or triple ho was employed to signify “mockery or scornful laughter” as early as the late 12th century, with its usage firmly established by the 16th century. A single ho, on the other hand, could indicate “astonishment, admiration, joy (often sarcastic), victory, [or] teasing.”

Although Santa Claus doesn’t mock or scorn, there’s a playful quality to his secretive nighttime visits to homes, and successfully pulling off such good-natured antics certainly calls for a celebratory ho or three. Indeed, the legend of Santa Claus is steeped in trickery—from parents striving to preserve the magic for their children to kids attempting to catch the elusive gift-giver in action.

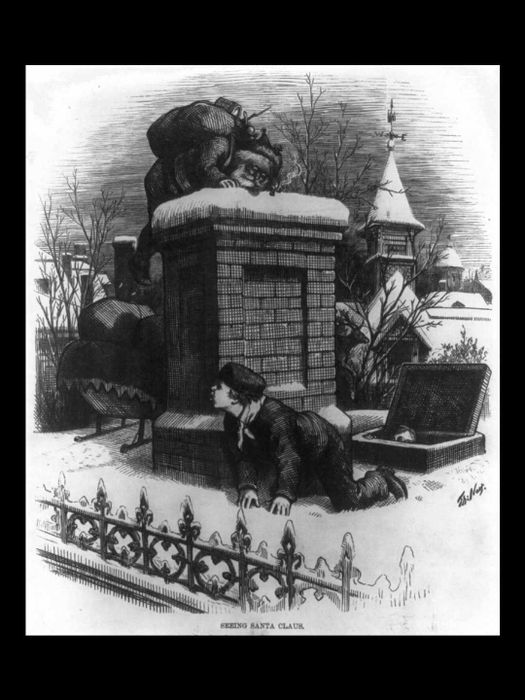

A Thomas Nast illustration featured in the January 1876 edition of 'Harper's Weekly.' | Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division Washington // No Known Restrictions on Publication

A Thomas Nast illustration featured in the January 1876 edition of 'Harper's Weekly.' | Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division Washington // No Known Restrictions on PublicationEarly references to ho ho ho in connection with Father Christmas—though not always uttered by him—highlight this playful theme. For example, in 1877, newspapers published a tale by John Brownjohn about a young boy named Miltiades Peterkin Paul who sets a steel trap in his stocking to catch Santa’s hand.

“I’ll rush downstairs right away and set him free. Ho! ho! ho! We’ll quickly find out if anyone can actually see him,” he declares. (Miltiades doesn’t catch Santa, but rather his own grandfather.)

A decade later, The Clyde Mail in Kansas featured an advertisement penned as if by Santa Claus, who had just “delivered” toys and various items to a nearby store in early December.

“Ha! Ha! Ha! Ho! Ho! Ho!” Santa exclaims, “Hello, Kids! You Weren’t Expecting Me This Early, Were You!”

Pre-Recorded Merriment

The association of ho ho ho with Santa Claus became even more entrenched, even as its linguistic subtleties started to diminish. This was primarily due to its perpetuation in songs and tales centered around Santa.

In 1867, for instance, William B. Bradbury released a hymnal that featured a song about Kris Kringle and his Christmas tree. The lyrics included, “Oh ho, Oh ho, ho, ho, ho, ho, ho, ho, ho, ho,” followed by a series of jingles.

The year before, Benjamin Russell Hanby had composed the music and lyrics for “Santa Claus,” a tune now more commonly known as “Up on the Housetop.” Originally, the line read, “O! O! O! Who wouldn’t go.” However, by the early 20th century, songbooks began substituting the o’s with ho’s. When Gene Autry’s famous version came out in 1953, it was officially titled “Up on the House Top (Ho! Ho! Ho!).”

The Wonderful Wizard of Oz author L. Frank Baum also played a role in popularizing the phrase. In his 1902 children’s book The Life and Adventures of Santa Claus, the main character joyfully sings this tune as his sleigh lifts off:

“With a ho, ho, ho!And a ha, ha, ha!And a ho, ho, ha, ha, hee!Now away we goO’er the frozen snow,As merry as we can be!”

It took some time before ho ho ho completely replaced ha ha ha as Santa’s signature laugh. For example, in Disney’s 1932 animated short Santa’s Workshop, Santa Claus distinctly says, “Ha! Ha! Ha!” instead of “Ho! Ho! Ho!” while reading letters and checking toys.

By the mid-20th century, the connection between the interjection and cheerfulness was so well-established that when vegetable producer Green Giant developed a jingle for the Jolly Green Giant in the early 1960s, they had vocalist Len Dresslar deliver a deep ho ho ho to follow the word jolly.

The Jolly Green Giant’s use of the phrase didn’t seem to diminish Santa’s image. And based on how many 6-year-olds today will enthusiastically respond to “Who says ho ho ho?” with “Santa!”, it’s evident who had the final laugh.