If you embarked on a journey to the Earth’s core like in Jules Verne’s iconic sci-fi novel, you wouldn’t encounter a herd of mastodons or a hidden sea where plesiosaurs freely swim. Instead, you'd face temperatures so extreme and pressure so intense that you would perish long before reaching your destination. In fact, the deepest humans have ever drilled into Earth is only about 7.6 miles.

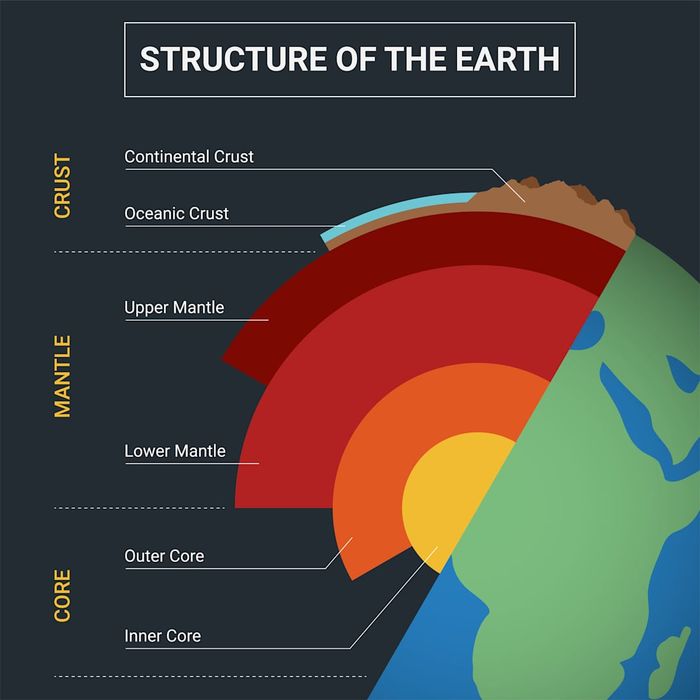

However, thanks to seismic waves generated by earthquakes, scientists have been able to map Earth’s inner layers. The planet is made up of four primary layers: the crust, mantle, outer core, and inner core. The crust, which is the outermost layer, is the thinnest, averaging about 19 miles deep on land and around 3 miles beneath the ocean. In some places on land, it can extend to nearly 50 miles deep.

The lower sections of the crust and the uppermost part of the mantle combine to form the lithosphere, which is home to tectonic plates. Beneath that, you find the asthenosphere of the mantle, followed by the lower mantle, and then a transitional layer between the lower mantle and outer core known as D” (pronounced “D double-prime”). Overall, the mantle is the Earth’s thickest layer, with an average radius of about 1800 miles, though this varies depending on the location.

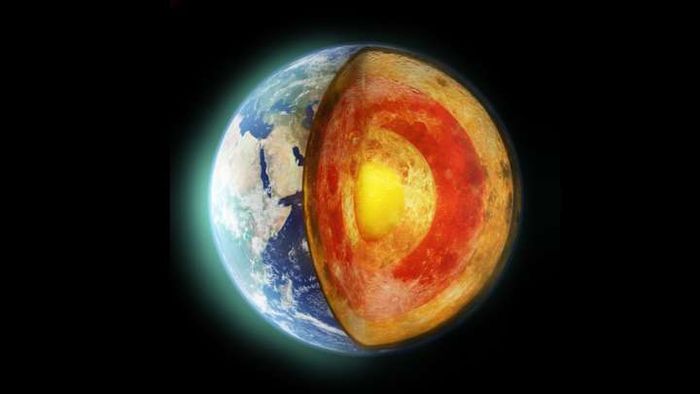

The rings aren’t as clear-cut in real life. | nutnai/iStock via Getty Images

The rings aren’t as clear-cut in real life. | nutnai/iStock via Getty ImagesThe mantle is predominantly solid rock, with the majority consisting of silicon-oxygen compounds known as silicates. Olivine and garnet are two major examples. Non-silicate elements found include iron, potassium, calcium, and others. Temperatures in the mantle are extremely high, ranging from about 1830°F to nearly 6700°F.

Beneath the mantle lies the outer core, which is roughly 1370 miles thick and is mainly composed of liquid nickel and iron. Further down, the inner core is a solid iron sphere (along with other materials) with a radius of nearly 760 miles. Despite temperatures exceeding 9300°F, the inner core remains solid, likely due to the immense pressure from the layers above it and the atmosphere preventing the iron from melting.

If you combine the thickness of both the inner and outer cores, it technically exceeds the thickness of the mantle. However, since the two are typically considered separate layers, the mantle is usually recognized as the thickest part of Earth.