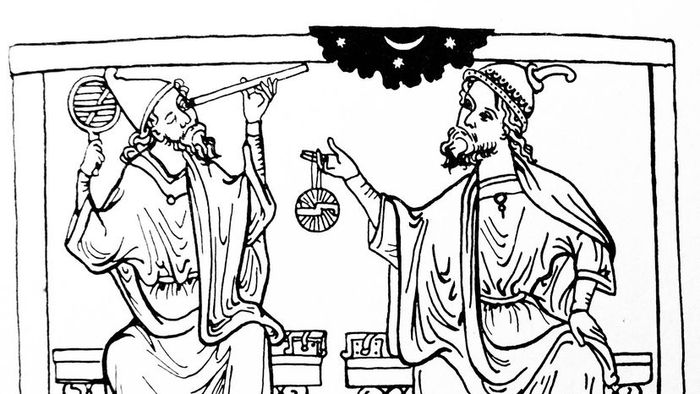

In this image, Euclid (on the left) is seen holding a sphaera while observing a dioptra. Next to him is Hermann of Carinthia, a medieval translator of Arab astronomical texts, holding an astrolabe. While Euclid's contributions to geometry are vast, should he be regarded as the first scientist? Photo12/Universal Images Group via Getty Images.

In this image, Euclid (on the left) is seen holding a sphaera while observing a dioptra. Next to him is Hermann of Carinthia, a medieval translator of Arab astronomical texts, holding an astrolabe. While Euclid's contributions to geometry are vast, should he be regarded as the first scientist? Photo12/Universal Images Group via Getty Images.Key Insights

- Determining the "first scientist" is challenging due to the evolution of scientific thought, but William Gilbert (1544-1603) stands out, especially for his groundbreaking research on magnetism and his influence on Galileo Galilei.

- Gilbert's seminal work, "De Magnete", presented replicable experiments, a fundamental aspect of the scientific method. He also proposed the Earth itself as a magnetic entity, a theory that paved the way for future scientific advancements.

- Although the term "scientist" was not coined until 1834, figures like Gilbert, who emphasized experimentation, observation, and a rejection of superstition, exemplify the core principles of modern science and laid the groundwork for the scientific methods we use today.

The term "scientist" first appeared in the English language in 1834, coined by Cambridge University historian and philosopher William Whewell. He used it to define someone who studies the physical and natural world through observation and experimentation. Therefore, one could argue that modern science had figures like Charles Darwin or Michael Faraday, Whewell's contemporaries, as its first practitioners. However, despite the absence of the term prior to the 1830s, there were already individuals whose work embodied these scientific principles.

To trace the origins of the very first scientist, we must venture even further back in time. One might look to the ancient Greeks, particularly Thales of Miletus (c. 624–c. 545 BCE), who is credited with significant achievements in both science and mathematics. Yet, like the legendary Homer, Thales left no written records, and there is even speculation that he might have been more of a mythical figure, credited with accomplishments that may never have been his.

Other ancient Greek figures, such as Euclid (the father of geometry) and Ptolemy (the astronomer who mistakenly placed Earth at the center of the universe), could also be considered. But despite their brilliance, these thinkers relied more on theoretical arguments than on conducting experiments to test or refute hypotheses.

Some scholars argue that the foundations of modern science were laid earlier in the Middle East, where a group of remarkable Arabic mathematicians and philosophers, working centuries before the European Renaissance, made significant contributions. This group included al-Khwarizmi, Ibn Sina, al-Biruni, and Ibn al-Haytham. Ibn al-Haytham, who lived between 965 and 1039 CE in what is now Iraq, is often recognized as the first true scientist. He invented the pinhole camera, discovered the laws of refraction, and studied natural phenomena such as rainbows and eclipses. However, there is still debate over whether his methods were truly modern or closer to the practices of Ptolemy and earlier Greek thinkers. It's also uncertain whether he fully emerged from the mysticism that still dominated his time.

While it's challenging to pinpoint when mysticism fully disappeared from scientific thought, certain characteristics of modern scientists are clearer. According to author Brian Clegg, a modern scientist must prioritize experimentation, embrace mathematics as a core tool, analyze information impartially, and be able to communicate effectively. In essence, a modern scientist must be free from religious dogma and capable of objective observation and thinking. Many figures from the 17th century, such as Christiaan Huygens, Robert Hooke, and Isaac Newton, embodied these qualities. However, to find the first scientist with all these characteristics, we must look to the Renaissance, specifically the mid-16th century.

We'll be moving on to that next.

Gilbert Claims the Title of First Scientist

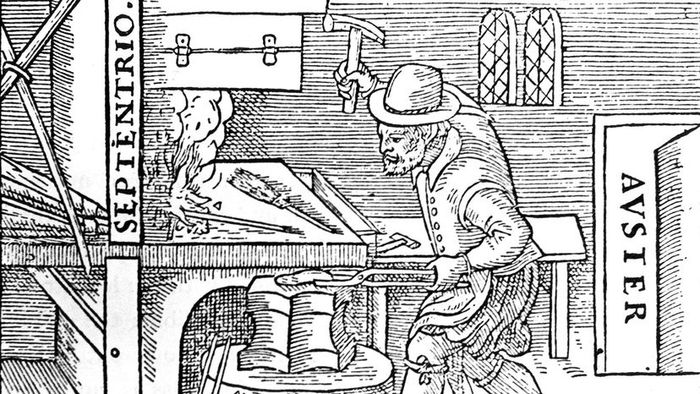

William Gilbert shapes a magnet. From "De Magnete" by William Gilbert, published in London, 1600. Photo 12/Universal Images Group via Getty Images

William Gilbert shapes a magnet. From "De Magnete" by William Gilbert, published in London, 1600. Photo 12/Universal Images Group via Getty ImagesWhen you think of Renaissance science, you likely think of Galileo Galilei, and rightfully so. He challenged Aristotle's views on motion and started explaining complex ideas like force, inertia, and acceleration. Galileo built one of the first telescopes, which allowed him to explore the universe and reveal that Earth was not the center of the cosmos but rather in its correct position. His emphasis on observation and experimentation was central to his work. However, much of Galileo's groundbreaking contributions owe their roots to another pivotal figure who was born two decades earlier.

He was William Gilbert, a somewhat overlooked figure in the history of science. Along with Galileo, Gilbert was actively engaged in applying the scientific method to his research and set a strong example for others after the first decade of the 17th century. As John Gribbin mentioned in his 2002 book, "The Scientists":

Born in 1544 to a distinguished family, Gilbert attended Cambridge University from 1558 to 1569. He later moved to London and had a successful career as a physician, serving Queen Elizabeth I and, after her death in 1603, King James I.

However, it was Gilbert's research into magnetism that might have earned him the title of the first modern scientist. His work culminated in "De Magnete, Magneticisque Corporibus, et de Magno Magnete Tellure" ("On the Magnet, Magnetic Bodies, and the Great Magnet of the Earth"), the first major book on physical science published in England. In the book’s preface, Gilbert emphasized the importance of "reliable experiments and solid arguments" over "speculations and the theories of philosophical thinkers." He also stressed the need for experiments to be carried out "with care, skill, and precision, not recklessly or clumsily."

Gilbert followed his own principles. His book provided such detailed accounts of his investigations that others could repeat his experiments and confirm his findings. His research led to groundbreaking discoveries in magnetism. He was the first to fully explain the workings of the magnetic compass and to propose that Earth itself was a magnetic body. His curiosity even extended to the cosmos.

Galileo was directly influenced by Gilbert. The renowned Italian scientist read "De Magnete" and replicated many of its experiments. It's easy to picture Galileo studying the book, nodding in agreement with Gilbert's emphasis on experimentation and observation — principles that Galileo would later apply in his groundbreaking work. Is it any surprise that Galileo declared Gilbert the founder of the scientific method? This endorsement could very well validate the assertion that William Gilbert was the first modern scientist.

Many science texts credit Francis Bacon as the father of the scientific method. So, doesn't that make him the first scientist? It depends. Bacon certainly played a key role in popularizing the techniques of scientific inquiry, but he was more of a philosopher than a hands-on experimenter. In contrast, William Gilbert and Galileo were true scientists. They designed experiments, carried them out, and documented their findings — just like you would in a high school physics lab. This dedication to rigorous, repeatable experiments is a defining feature of modern science.