A small blue-and-white cap, surrounded by rubble, is all that seals the Kola Superdeep Borehole, which plunges 40,230 feet (12,262 meters) beneath the surface. Wikimedia/(CC BY-SA 4.0)

A small blue-and-white cap, surrounded by rubble, is all that seals the Kola Superdeep Borehole, which plunges 40,230 feet (12,262 meters) beneath the surface. Wikimedia/(CC BY-SA 4.0)Key Insights

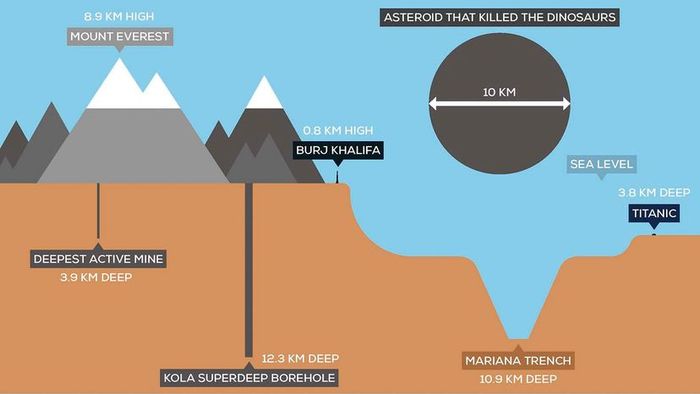

- The Kola Superdeep Borehole, situated in Russia, holds the title of the deepest man-made hole, reaching 40,230 feet (12,262 meters) or 7.6 miles (12.2 kilometers), surpassing both the Mariana Trench and the height of Mount Everest.

- Initiated by the Soviet Union in 1970, the drilling project uncovered surprising results, including the absence of the "Conrad discontinuity" (the transition from granite to basalt), the discovery of liquid water at unforeseen depths, and microscopic fossils from single-celled marine organisms that are 2 billion years old.

- Despite its impressive depth, the drilling faced significant difficulties, including rising temperatures and rock densities, causing the project to halt in 1992 and the borehole to be sealed in 2005.

While the United States and the USSR were focused on space exploration during the iconic space race of the 1960s, they were also competing for dominance in another arena: a race to the Earth's core, or at least as close as they could get. This rivalry led to the creation of the world's deepest hole.

The Deep-Drilling Race

In 1958, the United States launched Project Mohole, a mission to retrieve a sample from Earth's mantle by drilling through the ocean floor off Guadalupe Island, Mexico. With funding from the National Science Foundation, they managed to drill 601 feet (183 meters) into the seabed before the U.S. House of Representatives terminated the project in 1966.

In 1970, the Soviets made their move, beginning a drilling project in Murmansk, Russia, near the Norwegian border and the Barents Sea. Known as the Kola Superdeep Borehole, their effort proved more successful, reaching much deeper into the Earth and gathering samples that continue to amaze scientists today.

Why dig so deep into the Earth? "To answer fundamental scientific questions" that could shed light on some of the greatest mysteries about our planet, says Dr. Ulrich Harms.

Harms leads the German Scientific Earth Probing Consortium at the German Research Centre for Geosciences in Potsdam, Germany. He has visited the Kola Borehole, explored its core sample repository, and even examined the now-abandoned wellhead.

Although the Kola Superdeep Borehole never pierced deeper than Earth's crust, it still holds the record as the deepest hole ever dug.

The Kola Borehole's Depth

The Kola Superdeep Borehole in Russia is the deepest man-made hole on Earth. It surpasses the depth of the Mariana Trench and is even deeper than the height of Mt. Everest. – Simon Kuestenmacher

The Kola Superdeep Borehole in Russia is the deepest man-made hole on Earth. It surpasses the depth of the Mariana Trench and is even deeper than the height of Mt. Everest. – Simon KuestenmacherThe Kola Superdeep Borehole, located in Russia, holds the record as the deepest hole ever drilled on Earth. It surpasses both the Mariana Trench and Mount Everest in depth.

In a derelict drilling site surrounded by decaying wood and rusted metal remnants—once part of a Russian derrick and its surrounding structures—there rests a small yet durable maintenance hole cover, bolted securely with numerous corroding bolts.

Beneath the surface, nearly invisible to the naked eye, lies the world's deepest artificial hole, measuring only 9 inches (23 centimeters) in diameter.

The Kola Superdeep Borehole extends approximately 40,230 feet (12,262 meters) or 7.6 miles (12.2 kilometers) deep into the Earth's crust. To put it in perspective, the depth of the borehole equals the combined height of Mount Everest and Mount Fuji. It also reaches farther than the deepest point of the ocean, the Mariana Trench, which plunges to 36,201 feet (11,034 meters) below sea level in the Pacific Ocean.

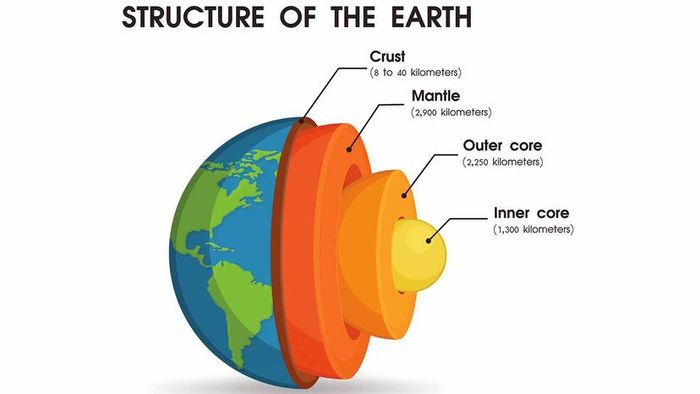

For reference, the Earth's outermost layer—the continental crust—is roughly 25 miles (40 kilometers) thick, a fundamental part of the planet's structure.

The mantle stretches for another 1,800 miles (2,896 kilometers), continuing beneath the Earth's surface. The outer core, which lies beneath it, extends for about 1,400 miles (2,250 kilometers) before reaching the dense, hot inner core, a mostly iron sphere with a radius of approximately 758 miles (1,220 kilometers).

While the deepest artificial point ever drilled is remarkable, it is surprisingly shallow when compared to the full depth of the Earth. The Kola Superdeep Borehole, for instance, only penetrates about one-third of the Earth's crust and just 0.2 percent of the total distance to the Earth's center.

The drilling project at Kola lasted for years. Starting on May 24, 1970, the aim was to drill as deep as possible. Back then, scientists estimated that they would reach a depth of around 9.3 miles (15 kilometers). By 1979, the project had already shattered world records by surpassing 6 miles (9.5 kilometers) in depth, making it the deepest man-made hole at that time.

In 1989, the drilling reached a remarkable depth of 40,230 feet (12,262 meters), setting the record for the deepest point ever reached by humans. At this depth, temperatures in the borehole soared from the anticipated 212°F (100°C) to an astounding 356°F (180°C).

Even after drilling over 40,000 feet (12,192 meters) into the Earth, researchers have only scratched the surface of the planet's crust. CRStocker/Shutterstock

Even after drilling over 40,000 feet (12,192 meters) into the Earth, researchers have only scratched the surface of the planet's crust. CRStocker/ShutterstockWhy Drill So Deep into Earth?

We drill deep holes for a variety of reasons, with the primary purpose being to extract valuable resources such as fossil fuels and metals.

Other notable examples of deep excavations include the century-old Bingham Canyon copper mine, located in the mountains near Salt Lake City. This massive pit stretches three-quarters of a mile (1.2 kilometers) deep and spans 2.5 miles (4 kilometers) in width. Another famous deep site is the Kimberley Diamond Mine, also known as The Big Hole, in South Africa—one of the largest manually-dug holes in the world, created without machinery.

Holes are also dug for scientific purposes, says Harms, to gain a deeper understanding of various natural processes and phenomena.

- Geohazards such as earthquakes and volcanic eruptions

- Geo-resources including geothermal heat and energy

- Understanding the evolution of Earth and life on it

- Studying past environmental changes to improve future predictions

"A specific example is that by observing regions near earthquake zones, researchers can track even the smallest earthquakes as they begin and spread in response to stress and strain," explains Harms. "Our goal is to capture near-field physical, chemical, and mechanical data to better understand these processes, which cannot be easily replicated in laboratory settings or by computer models."

Why Digging So Deep is Challenging

The Kola Superdeep Borehole was abandoned in 1992 following the collapse of the Soviet Union. Today, it lies in a state of ruin. Wikimedia/(CC BY-SA 4.0)

The Kola Superdeep Borehole was abandoned in 1992 following the collapse of the Soviet Union. Today, it lies in a state of ruin. Wikimedia/(CC BY-SA 4.0)In 1977, NASA launched Voyager 1 on its journey beyond the solar system into interstellar space. By August 2022, the spacecraft had traveled 14.6 billion miles (2 billion kilometers) away from Earth. This raises a fascinating question: why has it only taken engineers 20 years to drill just a few miles beneath the Earth's surface?

Drilling a hole to the Earth's center turned out to be more challenging than scientists anticipated. During the 1970s, when drilling began at the Kola Superdeep Borehole, the team made quick progress through granite rock. However, once they reached a depth of 4.3 miles (6.9 kilometers), the rock layers became significantly denser, making it much harder to continue drilling.

This difficulty caused drill bits to break, and the team had to alter the drilling direction multiple times. As a result, several different drill paths were followed until they finally established a near-vertical path, which Harms describes as resembling a Christmas tree shape.

Despite the challenges, the engineers pressed on. However, as the drill descended, the Earth's heat increased significantly. The temperature followed the scientists' predictions down to about 10,000 feet (3,048 meters). Beyond that depth, though, the heat surged unexpectedly, reaching 356 degrees Fahrenheit (180 degrees Celsius) at a depth of 7.5 miles (12 kilometers).

This temperature was far higher than the anticipated 212 degrees Fahrenheit (100 degrees Celsius), marking a significant deviation from their expectations.

Engineers also discovered that beyond the first 14,800 feet (4,511 meters), the rock became much more porous and permeable. Coupled with the extreme heat, this caused the rock to behave more like a plastic substance than a solid, making further drilling nearly impossible.

These high temperatures were far beyond what their drilling tools could handle. Although the Soviets continued their efforts until 1992, they never managed to surpass the depth they reached in 1989. Ultimately, the drilling operation was halted, leaving the 9.3-mile (15-kilometer) target unachieved. The site was officially closed and sealed in 2005.

Other countries, including Germany, Austria, and Sweden, have attempted similar projects over the years. However, none of these holes have exceeded the depth of the Kola Superdeep Borehole, although some were longer due to deviating from their original vertical paths.

What'd They Find in the Kola Superdeep Borehole?

(Starting from the top left) Workers inside the drilling room; a core sample taken from the Kola well; a fragment of metabasalt rock retrieved from a depth of 6,238.25 meters (20,465 feet) within Earth's crust. Pechenga

(Starting from the top left) Workers inside the drilling room; a core sample taken from the Kola well; a fragment of metabasalt rock retrieved from a depth of 6,238.25 meters (20,465 feet) within Earth's crust. PechengaThe Kola Superdeep Borehole provided many new insights for scientists. For example, they realized the Earth's internal temperature map needed to be revised after encountering temperatures far higher than anticipated.

They were also astonished to find no clear boundary between granite and basalt, which geologists refer to as the 'Conrad discontinuity.' This boundary had been theorized based on seismic-reflection surveys.

Another surprising discovery was the presence of liquid water at depths far greater than previously thought possible. 'One of the most unexpected findings was the presence of open saline water-filled cracks, indicating that the crust is not as solid as believed, and that there are pathways that allow fluids to flow,' says Harms.

Researchers theorized that the water may have been forced out of rock crystals due to the extreme pressure within the Earth.

Even more exciting was the discovery of biological activity in the rocks. At 4.4 miles (7 kilometers) deep, researchers found dozens of fossils from single-celled marine organisms dating back 2 billion years. The clearest evidence was microscopic fossils encased in organic compounds that were surprisingly intact despite the extreme pressures and temperatures of the surrounding rock.

Can We Dig Deeper?

Yes, eventually. But, Harms says, "digging deeper than 12 kilometers (7.45 miles) depends on two critical factors: temperature and borehole stability, the latter being dependent on stress, strain, and drilling fluid composition and weight."

That'll take some pretty technologically advanced equipment, considering temperatures there are predicted to be as high as 500 degrees Fahrenheit (250 degrees Celsius).

The real pie in the sky — or rather, in Earth — would be reaching Earth's mantle, the layer that begins just past Earth's crust, about 25 miles (40 kilometers) below our feet.

"By drilling, we can uncover valuable information about the mantle," Harms explains. "Earth scientists seek direct access to the in situ mantle to explore the nature of this debated boundary. We still lack fresh samples that could offer clues on how the crust and mantle interact, how fluids and magma droplets move from the mantle into the crust and eventually into the hydrosphere, and how they contribute to the biosphere — or how matter may return to the mantle."

"The grand processes that shape our planet remain mysterious at this boundary. The Moho Discontinuity [the boundary between Earth's crust and the mantle] stands as a central scientific objective."

In 2021, scientists in Japan achieved a significant feat by drilling the deepest ocean hole into Earth's crust, reaching 26,322 feet (8,022 meters), as part of the International Ocean Discovery Program (IODP).