Getty Images

Getty ImagesAncient Egypt evokes visions of majestic pharaohs, towering pyramids, and tombs filled with treasures of gold. Long before archaeology became a recognized science, adventurers plundered Egyptian sites, taking countless priceless artifacts.

While collectors recognized the value of these items, they couldn't fully grasp their historical significance. The civilization's records and monuments were inscribed in hieroglyphics, an ancient Egyptian script that remained undecipherable, leaving Egypt's past shrouded in mystery.

Everything changed with the discovery of the Rosetta Stone. But what exactly is the Rosetta Stone?

What Is the Rosetta Stone?

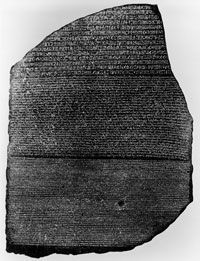

The Rosetta Stone is a piece of a stela, a standalone stone slab engraved with Egyptian governmental or religious texts, which enabled scholars to decode ancient Egyptian hieroglyphs for the first time.

Crafted from black basalt, it weighs approximately three-quarters of a ton (0.680 metric tons). The stone measures 118 cm (46.5 in.) in height, 77 cm (30 in.) in width, and 30 cm (12 in.) in depth — comparable in size to a medium LCD television or a sturdy coffee table [source BBC].

However, the inscriptions on the Rosetta Stone hold far greater importance than its physical makeup. It contains three columns of text, each conveying the same message in three distinct languages: Greek, hieroglyphics, and Demotic.

By studying the Greek and Demotic texts, scholars were able to decode Egyptian hieroglyphs. The Rosetta Stone served as a crucial translation tool, unlocking over 1,400 years of ancient Egyptian history and secrets [source: Cleveland MOA].

Rosetta Stone Controversy

The story of the Rosetta Stone's discovery and translation is as intriguing as the secrets it unveiled. From the moment it was found, it sparked controversy, unearthed during a time of war and Europe's pursuit of global dominance.

The translation of the stone fueled tensions between nations, and even today, experts argue over who deserves credit for cracking the hieroglyphic code. The stone's current home is also a topic of dispute. This artifact has consistently influenced history and politics in profound ways.

Since 1802, the Rosetta Stone has been housed in London's British Museum. While many visitors see it as a vital historical artifact, others treat it with the reverence of a sacred relic. Though now protected in a display case, it was once possible for visitors to touch the stone and trace its enigmatic hieroglyphs with their own hands.

History of the Rosetta Stone

For hundreds of years, Egyptian hieroglyphics remained an enigma to researchers.

Rraheb/Dreamstime.com

For hundreds of years, Egyptian hieroglyphics remained an enigma to researchers.

Rraheb/Dreamstime.comScholars struggled for centuries to decode Egyptian hieroglyphics.

The true importance of the Rosetta Stone lies not in its message but in the languages it features. Dated March 27, 196 B.C., the stone bears a decree from Egyptian priests praising the pharaoh as a virtuous and devout leader who honors the Egyptian gods [source: BBC].

Below the decree, instructions detail how the message should be disseminated: The priests ensured its widespread reach by mandating it be inscribed in three languages and etched into stone.

The Rosetta Stone, while not inherently unique compared to other stelae from its era, stands out due to its preservation. It offers invaluable insights into Egypt's history and the evolving power dynamics during the Greco-Roman period, when the region was governed by Macedonians, Ptolemies, and Romans. Following the pharaohs, including Cleopatra as the final ruler, Egypt saw successive rule by Coptic Christians, Muslims, and Ottomans from 639 to 1517 C.E. [source: BBC].

The arrival of diverse rulers brought sweeping transformations to Egyptian society, most visibly reflected in the evolution of its written language. New religions replaced ancient deities, leading to the decline of hieroglyphics, once the most sacred form of writing.

A Nation of Many Tongues

For generations, Egyptians chronicled their history using hieroglyphics, a script reserved for religious and governmental purposes. This intricate language adorned tombs, temples, and monuments, preserving their legacy.

Given the complexity and sanctity of hieroglyphics, Egyptians introduced hieratic, a simplified script for administrative and commercial records. Unlike hieroglyphics, hieratic was not employed for sacred texts.

During the Ptolemaic era, when the Rosetta Stone was created, Egyptians had adopted Demotic, a further simplified form of hieroglyphics. By having the decree on the Rosetta Stone written in three languages, the priests ensured it could be understood by everyone in Egypt [source: Harvard].

Lost in Time

Up until the fourth century A.D., the Rosetta Stone remained fully legible. However, as Christianity spread across Egypt, hieroglyphics fell out of favor due to their connection with pagan deities. While Demotic avoided the stigma of hieroglyphics, it eventually transformed into Coptic, which combined the 24 letters of the Greek alphabet with additional Demotic characters to represent Egyptian sounds absent in Greek.

With the rise of Arabic, Coptic faded, severing the last link to hieroglyphics. Over a millennium of Egyptian history was lost as a result.

Egypt underwent sweeping changes, not just in language but also in politics and religion. Temples adorned with hieroglyphics lost their significance for both Egyptians and their new rulers, leading to their dismantling for construction materials. The Rosetta Stone, once part of this sacred architecture, was repurposed into a wall.

The Rosetta Stone would eventually be rediscovered as the old civilization crumbled and a new one emerged. Its true importance was only recognized during this period of transformation.

Discovery of the Rosetta Stone

Napoleon Bonaparte.

Time & Life Pictures/Getty Images

Napoleon Bonaparte.

Time & Life Pictures/Getty ImagesAt the end of the 18th century, Napoleon Bonaparte initiated the Egyptian Campaign, aiming to establish French control over Egypt. Colonizing the region would strengthen France's influence in the East [source: International Napoleonic Society].

This move was part of a broader strategy to dominate key Eastern territories, particularly India. By severing Britain's access to the Nile, Napoleon aimed to weaken British forces and their Eastern colonies.

Napoleon's strategy extended beyond military conquest. He orchestrated a comprehensive study of Egypt by forming a specialized team tasked with documenting its history, culture, environment, and resources.

Napoleon believed that to govern a nation effectively, one must understand it thoroughly. He established the Institute of Egypt, also referred to as the Scientific and Artistic Commission, comprising experts like mathematicians, chemists, engineers, and historians [source: International Napoleonic Society].

The Institute's mission was shrouded in secrecy, with members instructed to disclose only that their efforts were for the benefit of the French Republic.

The Institute played a pivotal role in Napoleon's vision for French control over Egypt. Guided by a 26-part manifesto, its objectives included promoting Enlightenment ideals, conducting extensive research on Egypt's history and current state, and advising the French Republic on Egyptian affairs [source: International Napoleonic Society].

British and French navies at Aboukir Bay.

Hulton Archive/Getty Images

British and French navies at Aboukir Bay.

Hulton Archive/Getty ImagesIn August 1798, Napoleon and his troops arrived at Aboukir Bay, Egypt. However, the British navy swiftly defeated the French, destroying their fleet and leaving the soldiers stranded in Egypt for nearly two decades [source: International Napoleonic Society].

Despite the setback, the French established themselves in the Nile Delta. While the military focused on fortifications and reconnaissance, the Institute of Egypt gathered artifacts, explored ancient ruins, and engaged with the local community.

The Institute took over Hassan-Kashif's palace, transforming royal chambers into libraries, labs, and even a menagerie. Where harems once entertained, local animals now roamed under the watchful eyes of scholars.

During the summer of 1799, while expanding Fort Julien in Rosetta, a French soldier uncovered a polished stone fragment with intricate carvings. Recognizing its potential importance, he handed it over to the Institute for further examination.

The Institute's experts identified the stone as a decree and began the painstaking task of translation. They named it the Rosetta Stone after its discovery site and wisely created copies of its inscriptions. These copies proved invaluable after the British claimed the stone and other artifacts under the Treaty of Capitulation [source: BBC].

Both the French and British recognized the immense value of the Rosetta Stone, yet deciphering the code inscribed on it would take years. Its true significance would only become clear over time.

Translating the Rosetta Stone

A photograph of the Rosetta Stone from the 1800s.

Hulton Archive/Getty Images

A photograph of the Rosetta Stone from the 1800s.

Hulton Archive/Getty ImagesScholars eagerly began translating the Rosetta Stone as soon as they obtained access to it or a copy of its inscriptions.

While the Greek and Demotic sections were translated relatively quickly, the hieroglyphics remained an enigma. A fierce intellectual rivalry emerged between British scholar Thomas Young and French scholar Jean-François Champollion, both determined to be the first to unlock the secrets of hieroglyphic writing.

The rivalry between their nations mirrored their personal competition, and even today, Britain and France continue to dispute who truly unlocked the secrets of hieroglyphics and which country rightfully possesses (or should possess) the Rosetta Stone.

During the Rosetta Stone's exhibition in Paris in 1972 to mark the 200th anniversary of its discovery, rumors swirled that Parisians might attempt to steal it. Additionally, the British and French clashed over the sizes of the portraits of Young and Champollion displayed with the stone, accusing each other of favoring one scholar over the other [source: Harvard].

Reverend Stephen Weston translated the Greek inscription, completing his work in April 1802. While Greek language and alphabet knowledge were limited among some professionals, the Western world had been familiar with Greek since the Renaissance, which revived interest in Greco-Roman culture. As a result, Weston's achievement garnered less attention compared to the breakthroughs that followed [source: BBC].

The hieroglyphic section of the stone posed the greatest challenge, but early scholars who deciphered the Demotic and Greek texts laid crucial groundwork. French linguist Antoine-Isaac Silvestre de Sacy (who mentored Champollion) and Swedish diplomat Johan David Åkerblad both successfully translated the Demotic inscription in 1802.

De Sacy identified proper names like Ptolemy and Alexander in the text, using them as a foundation to match sounds and symbols. Meanwhile, Åkerblad relied on his expertise in the Coptic language to advance his translation efforts.

Åkerblad observed parallels between the Demotic script and Coptic, using these similarities to identify words like "love," "temple," and "Greek." By building a basic framework of the Demotic alphabet from these words, he successfully translated the entire section.

Cracking the Hieroglyphic Code

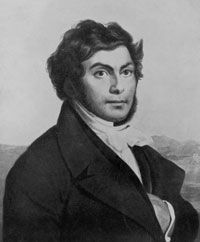

Jean-Francois Champollion.

Time & Life Pictures/Getty Images

Jean-Francois Champollion.

Time & Life Pictures/Getty ImagesEfforts to translate hieroglyphics began long before the Rosetta Stone's discovery. Horapollo, a fifth-century scholar, proposed a system linking hieroglyphics to Egyptian allegories.

Following Horapollo's theory, scholars spent 15 centuries pursuing an incorrect translation method. Even de Sacy, who had decoded the Demotic portion of the Rosetta Stone, attempted and failed to decipher the hieroglyphic inscription.

Deciphering the Cartouche

In 1814, Thomas Young achieved a major breakthrough by uncovering the significance of a cartouche [source: BBC]. A cartouche is an oval frame enclosing hieroglyphic characters, and Young deduced that these frames were reserved exclusively for proper names.

By identifying the pharaoh Ptolemy's name within a cartouche, Young made strides in his translation efforts. He theorized that names retain similar sounds across languages and used Ptolemy's name, along with his queen Berenika's name, to map out some phonetic elements of the hieroglyphic script.

However, Young's reliance on Horapollo's theory that hieroglyphics were purely symbolic hindered his understanding of their phonetic aspects. Despite abandoning the translation, he published his initial findings [source: BBC], which later became the groundwork for Jean-François Champollion's successful decipherment.

A Phonetic Revolution

In 1807, Champollion commenced his linguistic studies under de Sacy, acquiring the languages and expertise necessary for his eventual decipherment of hieroglyphics. Following Young's pivotal discovery in 1814, Champollion resumed his work from where he had paused [source: Ceram].

Champollion revisited the relationship between hieroglyphics and phonetics. He speculated that while the symbols might carry symbolic significance, they likely also corresponded to phonetic sounds, a common trait in many languages.

By 1822, Champollion had obtained ancient cartouches. He focused on a brief cartouche featuring four symbols, with the final two being identical. Recognizing the last two as the letter "s," he hypothesized that the initial symbol, a circle, could denote the sun.

In Coptic, an ancient language, the term for sun is "ra." By phonetically interpreting the cartouche as "ra - s s," Champollion deduced that the name Ramses was the only plausible fit.

This cartouche, featuring phonetic hieroglyphs spelling out Ramses, played a pivotal role in unlocking the mysteries of the Rosetta Stone.

Mytour 2007

This cartouche, featuring phonetic hieroglyphs spelling out Ramses, played a pivotal role in unlocking the mysteries of the Rosetta Stone.

Mytour 2007Establishing the link between hieroglyphics and Coptic demonstrated that hieroglyphics were not symbolic or allegorical but rather a phonetic system tied to sounds. Overwhelmed by this revelation, Champollion fainted immediately upon his discovery [source: Ceram].

Champollion, the Hieroglyphic Pioneer

At Champollion's birth, a fortune-teller predicted his future fame. His physical traits, including his bone structure, yellowish eyes, and dark complexion, hinted at his Egyptian ties, earning him the moniker "the Egyptian" [source: Ceram].

From a young age, Champollion was captivated by hieroglyphics and vowed to be the first to decode them. He pursued linguistic studies under Antoine-Isaac Silvestre de Sacy and applied to a Parisian institution. His thesis so impressed the admissions committee that they invited him to join their faculty.

A dedicated scholar, Champollion almost retreated into isolation. His brother Jean-Jacques championed his cause, even advocating to exempt him from military service. Ultimately, Champollion contributed more to his nation by dedicating himself to deciphering hieroglyphic texts.

Egyptology

Exhibition of Egyptian papyri in Turin, Italy.

AFP/Getty Images

Exhibition of Egyptian papyri in Turin, Italy.

AFP/Getty ImagesThe Rosetta Stone unlocked over a millennium of Egyptian history, sparking widespread fascination with the ancient civilization.

Napoleon aimed to unveil Egypt's secrets to the world, but his Institute faced limitations due to their inability to decipher hieroglyphics. Many of their findings relied on empirical evidence, leading to some inaccuracies. For example, they mistakenly dated the Dendra temple to an ancient era, when it was actually constructed during the Greco-Roman period (332 B.C.E. to 395 C.E.) [source: BBC].

Despite gaps and mistakes in their research, Napoleon's scholars compiled their observations into 19 volumes. Titled "A Description of Egypt," the Institute's work was completed in 1822, showcased at the Louvre in 1825, and supplemented with maps in 1828 [source: International Napoleonic Society].

The publication gained immense popularity across Europe, captivating both the general public and academics. Stories of mummies, grand tombs, and vast treasures fascinated people from all walks of life.

Deciphering the hieroglyphs on the Rosetta Stone was merely the beginning. It required years of examining countless papyri and studying monument inscriptions to piece together a comprehensive understanding of ancient Egyptian history.

Egyptology and Cultural Exchange

Many scholars dedicated themselves to exploring this ancient civilization. Consequently, Egyptology, the study of ancient Egypt, emerged as both a respected scientific discipline and a popular cultural subject.

Researchers traveled to Egypt to explore its ruins, archives, and relics. Authors such as Gustav Flaubert and Charles Dickens brought the allure of Egypt to those unable to visit, enriching their imaginations.

Numerous artifacts were transported to Europe under the guise of preservation. For years, Egyptians unaware of their cultural treasures' worth had been selling them to collectors. In the Middle Ages, mummies were frequently sold to European physicians, who believed powdered mummy remains could cure various ailments.

Egyptologists claimed that without transferring artifacts to European museums, they risked being sold off or disappearing entirely.

Replica of the Rosetta Stone.

AFP/Getty Images

Replica of the Rosetta Stone.

AFP/Getty ImagesChampollion advocated for housing these artifacts in the Egyptian National Museum. He argued that scholars also lacked the expertise to preserve them properly. For example, papyrus required storage in bamboo containers in dry conditions, yet many disintegrated into dust during their shipment to the West [source: Ceram].

The Egypt Exploration Fund, founded in 1895, aimed to assist museums in acquiring Egyptian art and antiquities. Advances in archaeology enabled researchers to uncover even more about Egypt's enigmatic history.

Modern Egyptologists conduct research and excavations to uncover fresh insights into ancient Egyptian civilization. Numerous universities now offer Egyptology as a formal academic discipline. The enduring allure of ancient Egypt in both popular and scholarly circles owes much to the pivotal role of the Rosetta Stone.