Getting Pop Rocks into stores came at a high cost—literally a finger.

In 1975, General Foods believed they had discovered a goldmine with Pop Rocks, a unique candy featuring tiny pebbles filled with carbon dioxide that crackled and fizzed in the mouth. While children adored its novelty, adults worried about the alarming rumors of stomach explosions. Journalists fueled the frenzy, highlighting the candy's scarcity and black-market resale, making it seem more like a forbidden commodity than a simple sweet.

While eating Pop Rocks posed no real danger, producing them was a different story. Mass-producing carbonated candy was a risky endeavor for General Foods, involving molten candy that could severely burn workers, requiring them to wear protective gear reminiscent of scenes from Breaking Bad. The candy had to be crushed under immense pressure after production, and in one tragic incident, a worker lost a finger when it got caught between machinery.

The candy's journey was fraught with challenges, including a delivery truck incident that literally exploded, limiting its availability across the country.

Accidental Genius

Pop Rocks were invented by William Mitchell, a food scientist at General Foods, who in 1956 was experimenting with creating a carbonated drink powder—essentially a fizzy version of Kool-Aid. The only successful result was tiny carbonated granules, which he tasted and discovered they crackled audibly once the sugar dissolved. Realizing the unique texture and popping sensation could be a hit, he shared it with fellow scientists.

“It turned into a challenge—who could swallow the largest piece,” Mitchell recalled in a 1979 interview with People. “We had a lot of fun that afternoon, wasting time, but I knew it was special from the beginning.”

General Foods initially hesitated. For 18 years, the fizzy candy—composed of sugar, lactose, corn syrup, and flavorings that trapped CO2 until dissolved—was mostly enjoyed by Mitchell’s family. It wasn’t until a management change sparked renewed interest that the company decided to test Pop Rocks in Canada in 1975.

Pop Rocks straight from the package. | Anthony, Flickr // CC BY-ND 2.0

Pop Rocks straight from the package. | Anthony, Flickr // CC BY-ND 2.0The decision to test the market in colder regions was deliberate. Pop Rocks struggled in hotter climates, often melting before they could deliver their signature popping sensation. The Indianapolis News reported an incident where a delivery truck's entire load of Pop Rocks overheated, causing an explosion that blew the doors open. General Foods acknowledged the event, reinforcing their concerns about temperature sensitivity.

In 1976, General Foods initiated a gradual nationwide release, steering clear of regions with temperatures above 85 degrees and halting distribution during summer months. (The limited availability was also due to a slow production process that posed risks to workers.) Grape, orange, and cherry flavors were sold for 15 to 25 cents per pack.

The candy delivered an instant sugar high for children. "It feels like raindrops falling on my tongue," remarked Roger Kirchner, a second-grader at Sacred Heart Grade School in Sauk Rapids, Minnesota. "It’s like having a popcorn machine going off in my mouth."

The unique appeal of Pop Rocks drove children to rush and buy the candy before it disappeared from stores. At Osco Drug in Saint Paul, Minnesota, staff sold 24,000 packages in just a few weeks.

Supply High

The limited availability of Pop Rocks in certain regions led to an uncomfortable comparison to illegal drugs—a thriving black market. Adults in states like Oregon and Washington, where the candy was sold, bought it in bulk and resold it in states without distribution at inflated prices, sometimes charging up to $1 per pack.

It wasn’t only adults exploiting the situation. “Kids would purchase the packets and resell them to their classmates at a hefty markup,” Mitchell explained to the Associated Press in 1979. “They were essentially running a mini racket.”

The New York Times journalist Lawrence Van Gelder playfully leaned into this analogy, noting in a May 19, 1978 article:

"One day last month, when Justin Prisendorf was still 9 years old, someone approached him at the prestigious Collegiate School and handed him a free sample of pink granules ... The next time Justin wanted more, he had to pay a dollar. Over a month has passed, and Justin is now 10. These days, he’s a regular user, purchasing a couple of envelopes weekly of a substance that costs $80 a kilo on the streets. In some areas, according to reports reaching the manufacturers, it can fetch up to $200 a kilo."

While no one was getting rich enough to buy a mansion like Scarface, Pop Rocks were still a lucrative venture. Even at 25 cents per pack, reselling them for 50 cents—a 100 percent profit—made cross-state trips worthwhile.

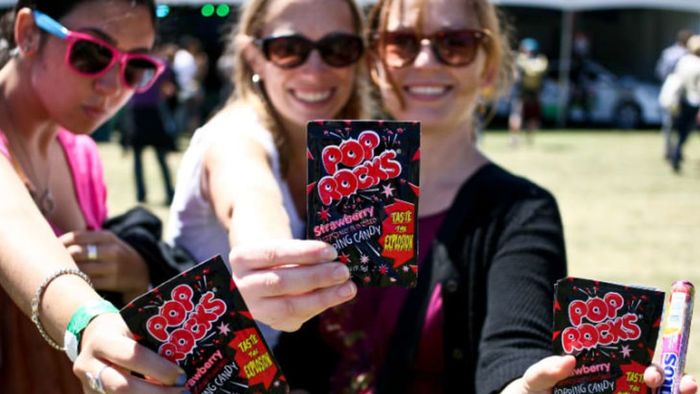

Pop Rocks turned into a black market commodity. | Alejandro De La Cruz, Flickr // CC BY 2.0

Pop Rocks turned into a black market commodity. | Alejandro De La Cruz, Flickr // CC BY 2.0The black market activity wasn’t just limited to consumers. Truck drivers in Canada were also suspected of smuggling the candy into Minnesota.

Fizzling Out

From the start, Pop Rocks sparked playground legends, with kids spreading stories of children dying after eating the candy, often claiming it was fatal when mixed with soda. John Gilchrist, the actor known as Mikey from the Life cereal ads (“Mikey likes it!”), was rumored to be the most famous casualty.

Mikey was perfectly fine. No one ever died from eating Pop Rocks, but the persistent rumors forced stores to remove them from shelves and prompted General Foods to dispatch Mitchell and other representatives to address the concerns. Mitchell emphasized that the candy contained only a tenth of the carbonation found in a soda can and that gas was the only potential side effect. The FDA had also approved the product after testing it in response to baseless claims of children exploding, even establishing a hotline in Seattle to reassure worried parents.

However, not all incidents were so easily dismissed. The FDA identified a few cases where children experienced minor discomfort from overindulging in Pop Rocks. “In verified cases, the issue was excessive consumption, particularly by young children,” FDA spokesperson Emil Corwin explained to Gannett News Service in 1979. “They weren’t eating one or two packs but six or more at once, often washing it down with carbonated drinks.”

“The outcome was predictable. It irritated the mouth’s mucus membrane, causing a red, sore tongue or throat, difficulty swallowing, and sometimes stomachaches in kids.” Corwin noted that children were essentially “misusing” the product.

Due to limited distribution, inflated prices, and rumors of child fatalities, Pop Rocks had a brief heyday, fading from the market by 1982. (Like many nostalgic items, they can still be purchased today.)

While Mitchell promoted a powdered alcohol project, it never materialized, as General Foods avoided the adult beverage market. Despite Pop Rocks selling 500 million packets by 1979, Mitchell’s reward was modest—a $5000 Chairman’s Award from General Foods.