From the iconic painting NightHawks to the beloved sitcom Seinfeld, New York City diners have become a cornerstone of American pop culture. If you’re in the U.S., chances are you have a favorite diner—whether it’s a 24-hour joint where you sipped coffee and munched on fries as a teenager or a cozy family-run spot where you enjoyed Sunday breakfasts (and likely ordered the same dish every time).

But how did these chrome-and-neon eateries come to be? Discover the origins of diners, from their humble Lunch Wagon roots to the famous “We Are Happy to Serve You” cups, as explored in an episode of Food History on YouTube.

Origins in Horse-Drawn Wagons

Diners originated as mobile food carts that emerged at night to provide simple meals for third-shift workers. These were actual horse-drawn wagons. While street food vendors have been around as long as cities, most offered limited menus, specializing in single items like pies or baked potatoes, and operated during daylight hours.

The first known nighttime food wagon was launched by Walter Scott in Providence in 1872. Scott sold sandwiches, coffee, and pies from his converted horse-drawn cart. His mobile eatery became so profitable that he left his printing job to focus on it.

Scott’s success inspired numerous New England entrepreneurs to replicate his model. These ventures, known as “Lunch Wagons,” functioned as 19th-century food trucks, moving between locations or staying stationary. Meals were prepared inside using basic stoves or stored in iceboxes, then served through a window to street-side customers.

Specialized manufacturers began producing or retrofitting these wagons. They featured ornate lettering, murals, and protective overhangs to shield customers from the elements. In 1887, one innovator introduced indoor seating, transforming Lunch Wagons into “Rolling Restaurants.”

The concept gained momentum with support from the temperance movement. For night workers, saloons were often the only open option, but lunch wagons offered an alcohol-free alternative with affordable coffee and sandwiches.

A stamp depicting a lunch wagon. | SOPA Images/GettyImages

A stamp depicting a lunch wagon. | SOPA Images/GettyImagesAs these wagons grew in popularity, they expanded their operating hours beyond nighttime, competing with traditional restaurants during the morning rush. This lightly taxed competition angered restaurateurs, saloon owners, and others frustrated by the wagons congesting busy streets. As a result, cities that had tolerated nighttime operations began restricting their daytime activities.

Wagon owners began parking on private property, allowing them to operate without interference from local authorities. With more permanent locations, these night lunch “wagons” evolved into lunch “cars.” By the 1920s, they were known as dining cars, eventually shortened to diners.

The seating typically consisted of a simple counter with stools, encouraging quick turnover. Jerry O’Mahony, a New Jersey-based manufacturer, shipped these cars nationwide. O’Mahony’s dining cars were largely stationary, earning him recognition as the inventor of the “diner”—a prefabricated restaurant inspired by railroad cars. Other companies sometimes repurposed decommissioned railroad cars, adding kitchens and indoor seating.

Palace Diner, constructed by Jerry O'Mahony, Inc. | FPG/GettyImages

Palace Diner, constructed by Jerry O'Mahony, Inc. | FPG/GettyImagesO’Mahony was among the earliest diner manufacturers in New Jersey, but many others followed. During the 20th century, New Jersey dominated the diner industry, producing roughly 95 percent of all prefabricated diners worldwide. These diners were shipped globally and could even be returned to factories for upgrades or repairs. However, many remained in the state, solidifying New Jersey’s reputation as the Diner Capital of the World, home to over 500 active diners today.

A diner named Casey’s, located in Natick, Massachusetts, holds the title of America’s oldest continuously operating diner. It began as a lunch wagon in the 1890s, with its current structure built in 1922 by the Worcester Lunch Car Company. Family-owned for four generations, it continues to serve breakfast, lunch, dinner, and a delightful selection of pies.

From Urban Centers to Suburban Sprawl

While lunch wagons originated in urban areas, diners found their true home in the suburbs. After World War II, many white Americans relocated to suburban regions like Long Island—and diners followed them there.

Coffee served in a diner. | Terry Vine/The Image Bank/Getty Images

Coffee served in a diner. | Terry Vine/The Image Bank/Getty ImagesGovernment programs made homeownership attainable, particularly for white men who had served in the military. The “American Dream” idealized a home with a white picket fence and a yard. Meanwhile, discriminatory practices like “redlining” and other financial barriers kept many families of color confined to urban neighborhoods.

Diners often mirrored this societal division, influenced by Jim Crow laws or de facto segregation stemming from geographic and economic disparities. Consider the diner’s relative, the lunch counter, and its significance during the civil rights movement through sit-ins.

Diners, to some degree, managed to bridge socioeconomic gaps within racially segregated communities. Often situated on the outskirts between urban and suburban areas, they served patrons from both settings. Their ability to cater to factory workers, office professionals, families, and individual diners highlights their broad appeal. However, their persistent racial segregation underscores the limitations of food as a unifying force.

Diner Design

Originally designed as mobile structures, diners were transported by truck to suburban locations. However, their role evolved upon arrival. No longer just catering to overnight male workers, they adapted to fit the family-centric lifestyle of post-World War II America.

Classic diner interior. | Burazin/The Image Bank/Getty Images

Classic diner interior. | Burazin/The Image Bank/Getty ImagesDiner interiors were revamped to reflect the era’s vision of a stylish, modern home, featuring “Formica countertops, porcelain tiles, leather booths, wood paneling, and terrazzo floors,” as Joan Russel noted in Paste magazine. These materials mirrored those found in the new suburban bungalows. While counters and stools stayed, booths and tables were introduced to accommodate groups, making them family-friendly. Many diners continued operating 24/7, catering to their original patrons. Over time, they evolved into hangouts for teenagers, offering a space for those too young for bars.

The 1950s diners, inspired by sleek, silvery railroad cars, featured shiny stainless-steel exteriors, neon signs, and a futuristic aesthetic. While some were freestanding structures, they retained their space-age look. Technically, these establishments were “coffee shops,” as the term diner specifically referred to prefabricated, factory-built restaurants transported to their locations.

Today, the term coffee shop often refers to chains like Starbucks, while diner has become the umbrella term for family-owned, often 24-hour eateries.

The Iconic Greek Diner

The American Northeast remains home to the highest concentration of traditional diners, with 2,000 spread across New England. However, their survival wasn’t guaranteed—the rise of chain restaurants in the 1960s threatened their existence. So, what kept them alive?

If you’ve spent time in the New York City area, you might recall a time when nearly every diner was run by a Greek family. Dan Georgakas, an anarchist poet and Greek-American historian, suggested this tradition stemmed from the kaffenion, a traditional Greek social space where men gathered to drink coffee and ouzo—an anise-flavored aperitif—while discussing daily life.

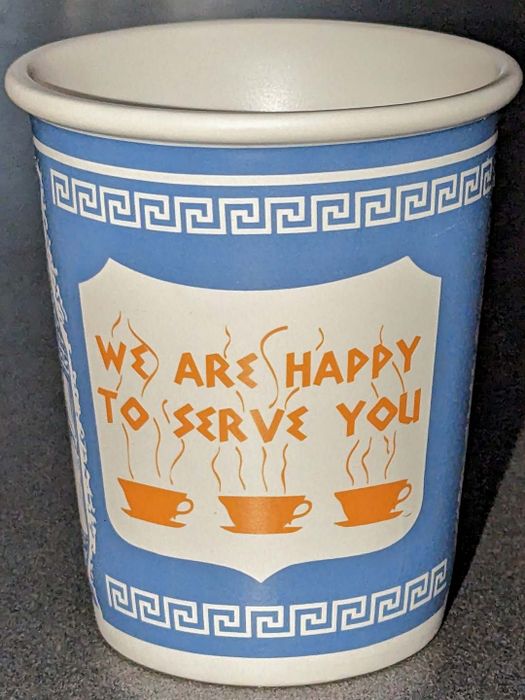

A ceramic replica of the "We Are Happy to Serve You" cup. | Macrakis, Wikimedia Commons // CC by SA 4.0

A ceramic replica of the "We Are Happy to Serve You" cup. | Macrakis, Wikimedia Commons // CC by SA 4.0As Greek immigration to New York surged in the early 20th century, these coffee shops also arrived, establishing themselves in Greek neighborhoods. While there may be a thematic link between these spaces and the Greek diners of the late 20th century, it was a later wave of immigrants, arriving post-1965, that cemented the iconic status of Greek-owned diners in New York.

Food-related businesses have long been a common entry point for immigrants building a new life in America. As WBUR reported, “the National Restaurant Association found in 2016 that 29 percent of restaurant and hospitality businesses are immigrant-owned, compared to just 14 percent of all U.S. businesses.”

Starting a food business doesn’t require significant capital or fluency in English. Employees often come from the same region or country, fostering a sense of community through shared language, religion, and traditions. In Greek diners, new immigrants typically began as dishwashers, advancing to busboys, cooks, and waiters until they accumulated enough savings to purchase their own diner.

New York’s Greek diners are known for their distinctive menus and interiors. The menus are often extensive, featuring everything from pancakes and lobster tails to omelets, spaghetti, moussaka, and matzoh ball soup. As New York Times writer Dena Kleiman observed in 1991, the Harvest Diner in Westbury, Long Island, offered a wide array of dishes, including oversized muffins and duck a l’orange. One Manhattan diner even boasts 220 menu items. “You have to cater to everyone,” explained Harvest Diner owner Charles Savva. New dishes introduced at one diner quickly spread to others.

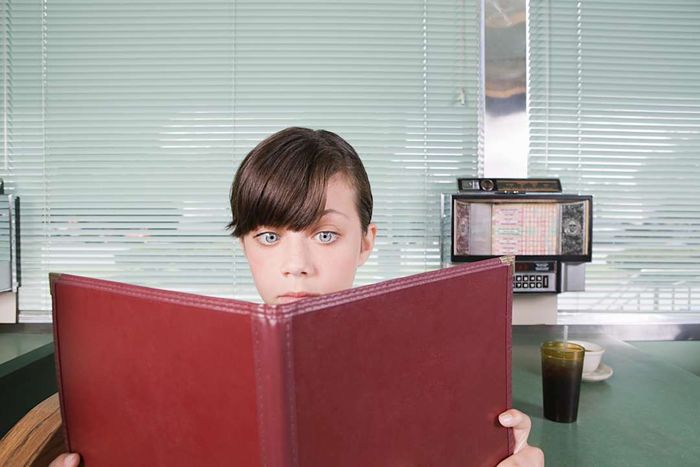

Some diner menus feature hundreds of options. | Image Source/Getty Images

Some diner menus feature hundreds of options. | Image Source/Getty ImagesIn a constant effort to stand out, diner owners expanded their menus and added extravagant decor, such as “chandeliers adorned with faux crystals [and] flowing draperies,” as reported by the Times. Greek statues, fountains, and LED light displays also became common. The iconic blue-and-white takeout coffee cups, often emblazoned with “We Are Happy to Serve You” and Greek-key patterns, have become so iconic that MOMA Design Stores now sells ceramic replicas.

The influx of Greek immigrants to New York City reached its height in the mid-1900s. By the early 2000s, many Greek diner owners started retiring, passing their businesses to a new wave of immigrants from regions like South Korea, Bangladesh, and Central America.

Modern-Day Diners

However, escalating real estate prices in the tri-state region are threatening the existence of many diners. Iconic spots have been replaced by upscale apartment complexes, while others have been overtaken by pharmacies or banks. The remaining diners must now contend with the growing presence of chain restaurants.

Tom’s Restaurant, as seen in 'Seinfeld,' captured by Roberto Machado Noa/GettyImages.

Tom’s Restaurant, as seen in 'Seinfeld,' captured by Roberto Machado Noa/GettyImages.Even before the COVID-19 pandemic disrupted dining out, diners faced significant challenges. Over the past 25 years, more than half of New York City's diners have shut down, with only 419 remaining open in 2019. Jeremiah Moss, the writer behind the blog Vanishing New York, captured the nostalgic feelings of many New Yorkers, stating: 'The longer you live in New York, the more you miss a city that no longer exists.'

Despite the challenges, some iconic New York City establishments persist. B&H Dairy, a kosher dairy restaurant in the East Village established in 1938, is now run by an Egyptian man and a Polish woman. Its diverse staff, representing various global backgrounds, proudly wear shirts declaring 'Challah, por favor!'

Among New York's oldest continuously operating diners is Nom Wah Tea Parlor, a dim sum restaurant on Doyers Street that opened in 1920. While dumplings and chicken feet might not be the first things that come to mind when thinking of diners, this iconic spot highlights the diverse culinary traditions that fall under the evolving 'diner' umbrella. Its vintage interior, largely unchanged since the 1960s, features classic elements like tile floors, formica tables, chrome stools, and red vinyl booths. Founded by immigrants, it offers affordable meals and remains deeply rooted in its community, even as it attracts tourists. In 2017, its Nom Wah Kuai location introduced the baogel, a creative fusion of bao buns and bagels.

For New Yorkers, diners are more than just eateries—they are hubs of community and occasionally fame. The exterior of Tom’s Restaurant in Morningside Heights gained widespread recognition through Seinfeld. These family-owned businesses often serve as sanctuaries for both biological and chosen families.

New York City, like the rest of the country, is constantly evolving. The future of diners remains uncertain. If you’re fortunate enough to have a family-run diner nearby, support them. Create new traditions over pancakes, revisit them after late nights like in your teenage years, or enjoy a hassle-free Sunday morning with hash browns, chicken fingers, and a martini from the same cozy booth. These cherished establishments deserve to welcome another generation of patrons. And, of course, don’t overlook their pies.