At his renowned restaurant El Bulli in Catalonia, Spanish chef Ferran Adrià created a dish that appeared simple yet was revolutionary: a tiny, spoon-sized imitation of a green olive. Upon tasting, this sphere dissolved into a burst of intense olive essence, surprising diners with its liquid core.

This culinary marvel was achieved through chemistry. Adrià combined olive juice, rich in calcium, with alginate, a seaweed-derived compound that forms strong bonds in the presence of specific chemicals. When calcium-rich mixtures are immersed in sodium alginate, a gel-like coating forms, creating spherical droplets via reverse spherification. Adrià’s olive puree, treated with sodium alginate, resulted in perfectly shaped, liquid-filled olives bursting with flavor.

Though El Bulli closed its doors in 2011, its impact on the culinary world remains profound. Was molecular gastronomy a groundbreaking innovation or an exclusive trend? What truly defines molecular gastronomy? Grab your agar-agar and prepare your centrifuge—let’s explore the contentious origins of this scientific approach to cooking.

The Centuries-Old Roots of Molecular Gastronomy

While molecular gastronomy is often linked to contemporary modernist cuisine, its roots stretch back hundreds of years. Food historian Gilly Lehmann notes that chefs in medieval and renaissance times were akin to scientists. They blended medical theories of their era into their cooking and utilized emerging scientific knowledge to enhance their culinary creations.

This is not an exaggeration: A 15th-century manuscript titled The Vivendier contains a perilous and nearly impossible recipe titled “Make that Chicken Sing when it is dead and roasted.” The method involves filling a chicken with sulfur and mercury, heating it, and manipulating the bird to produce sounds resembling a chicken’s cry.

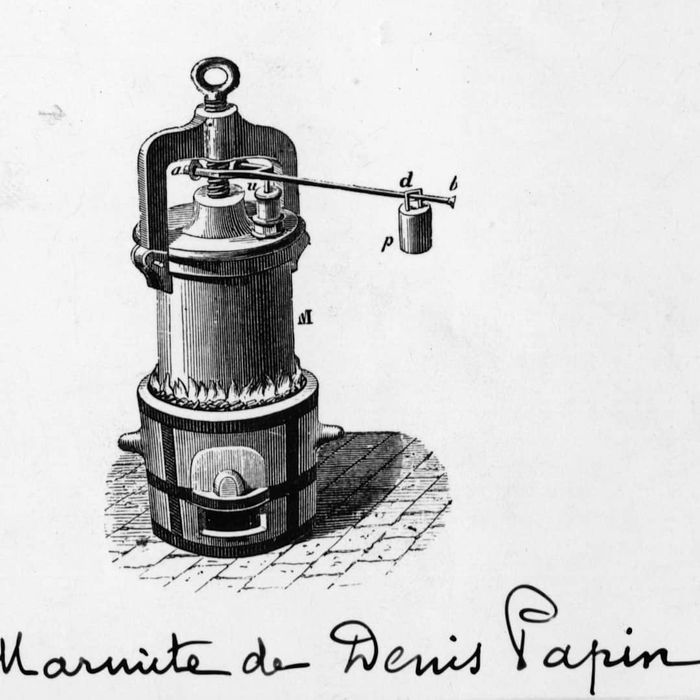

Denis Papin's bone digester. | Hulton Archive/GettyImages

Denis Papin's bone digester. | Hulton Archive/GettyImagesDuring the 17th century, French physicist Denis Papin developed a device known as the “digester.” A member of the Royal Society who examined the invention noted that it could transform “the toughest beef and mutton bones ... into a texture as soft as cheese.” Papin’s creation became the precursor to today’s pressure cooker.

The 18th century saw groundbreaking advancements in chemistry being integrated into cooking. French chemist Antoine Baumé introduced a technique to measure liquid density, now referred to as the Baumé scale. This method compares the density of a substance to that of water, providing valuable insights into liquid properties.

For decades, Baumé’s scale played a crucial role in food production, particularly in brewing and winemaking. Although it has been largely replaced by the Brix scale, some winemakers still use Baumé measurements to assess dissolved solids in grape juice. This helps estimate sugar content and predict the alcohol levels in the final wine. Baumé’s contributions advanced the scientific aspect of winemaking, balancing its artistic side.

Baumé’s legacy also includes the Baumé egg, created by soaking a whole egg in alcohol for approximately a month. The ethanol permeates the shell, coagulating the egg’s interior without the need for heat, effectively cooking it.

Understanding Molecular Gastronomy

Creating a Baumé egg feels more aligned with modern molecular gastronomy than traditional frying, though the distinction isn’t always clear. After all, heating an egg also involves molecular changes. Similarly, curing meat, fermenting vegetables, and countless other food preparation or preservation methods humans have used for centuries are also molecular processes. This ambiguity makes defining molecular gastronomy a challenge.

Hervé This, a scientist, magazine editor, and pioneer in the field, differentiates

Today, molecular gastronomy is often associated with the fusion of food, science, and theatrical presentation, as showcased in restaurants like El Bulli. This approach has historical roots in culinary traditions that blend innovation and artistry.

Marie-Antoine Carême. | Heritage Images/GettyImages

Marie-Antoine Carême. | Heritage Images/GettyImagesIn the early 19th century, French chef and cookbook author Marie-Antoine Carême gained fame for his innovative, presentation-focused culinary style. While it lacked the chemical techniques central to modern molecular gastronomy, it masterfully blended art and science through edible architecture. Carême’s creations, such as the towering croquembouche made of choux pastry puffs, were designed to delight both the eyes and the taste buds. He crafted elaborate desserts resembling ancient temples and pyramids, famously stating in one of his cookbooks: “I want order and taste. A well-presented meal is enhanced one hundred percent in my eyes.”

Carême’s haute cuisine captivated the wealthy, but he aimed to make his techniques accessible. In his numerous cookbooks, he provided detailed instructions for replicating complex dishes in home kitchens. According to Eater, Carême was the first to use the phrase you can try this for yourself at home, making fine dining techniques approachable for everyday cooks.

The Workshop That Coined the Term Molecular Gastronomy

While Carême’s work hinted at the future of molecular gastronomy, the term itself emerged much later. In 1988, cooking instructor Elizabeth Cawdry Thomas and physics professor Ugo Valdrè met in Italy and envisioned a workshop exploring the science of food. At the time, culinary science was primarily used by industrial food producers, not home or restaurant chefs. Their idea led to the Erice Workshops, which launched in Sicily in 1992.

The term molecular gastronomy debuted at these workshops, as noted by Dr. Harold McGee, a co-organizer. Initially promoted as an “International Workshop on Molecular and Physical Gastronomy,” the event focused on understanding the science behind traditional cooking rather than the theatrical dining style that later gained popularity. McGee explains, “The purpose was to understand traditional cooking—the science of foods considered the pinnacle of culinary art.” The choice of molecular reflected the era’s fascination with molecular biology, a field that captured public interest in the early 1990s.

Cawdry Thomas enlisted Oxford physicist Nicholas Kurti to direct the workshop, with Hervé This also joining the initiative. Beyond the planning phase, Cawdry Thomas actively led sessions, including a blind tasting of tomatoes paired with different salts and another comparing microwave-cooked foods to those prepared using traditional methods.

Despite her pivotal role, Cawdry Thomas’s contributions have often been overshadowed, with media attention focusing more on This and Kurti.

“The professional hierarchy played a role,” McGee explains. “Physics professors were seen as more prominent than cooking school instructors, and the male-dominated fields of both cooking and science further marginalized her. To my knowledge, no female chefs were invited to the event. Elizabeth was the driving force behind the scenes, facilitating connections and ensuring everything ran smoothly. She preferred staying out of the spotlight, but that doesn’t diminish her essential contributions. Without her, the workshop likely wouldn’t have happened.”

The workshop aimed to unite chefs, writers, and scientists to explore four key areas: existing knowledge about the science of cooking, how scientific insights could enhance traditional methods, the potential for new techniques and ingredients, and the adaptation of industrial food processing methods for smaller kitchens.

While these gatherings are often seen as the foundation of modern molecular gastronomy, their focus was not on creating extravagant dishes for high-end menus. Instead, participants prioritized the practical use of science to advance culinary practices on a broader scale.

Ferran Adrià and the Rise of Molecular Gastronomy at El Bulli

During the same period as the Erice workshops, Ferran Adrià was revolutionizing cooking with his innovative use of foams and precise techniques, which are now synonymous with molecular gastronomy.

“The Erice workshops aligned with the culinary zeitgeist of the time. Traditional French cooking, epitomized by Escoffier’s methods, had become the standard in international hotel kitchens,” McGee explains. “In the 1960s, France saw a cultural shift with nouvelle roman, new cinema, and nouvelle cuisine. What emerged in Spain, particularly through Ferran Adrià, felt like a dynamic evolution of this movement. Adrià was, in many ways, the Gaudí of the culinary world.”

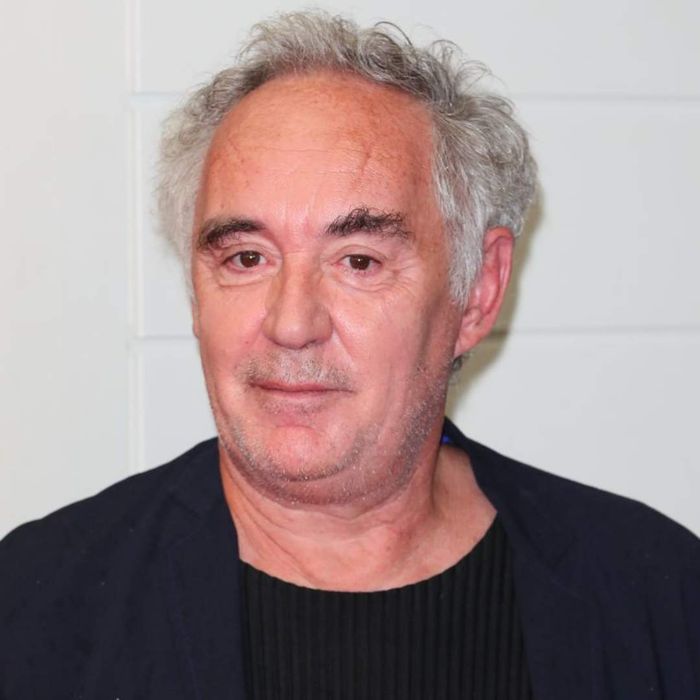

Chef Ferran Adrià. | JB Lacroix/GettyImages

Chef Ferran Adrià. | JB Lacroix/GettyImagesMcGee describes Adrià as having “a revolutionary mindset that greatly benefited from a scientific understanding of food and cooking. This is one reason why the science behind food preparation gained widespread interest. Adrià took ordinary ingredients and transformed them into entirely new forms, altering the dining experience. For instance, a lettuce leaf’s taste is predictable, but a green blob leaves you guessing until you taste it.”

The flavored foams, created using whipped cream canisters, became so iconic that they inspired numerous imitations, often seen as masking mediocre cooking. In a Robb Report article by Jeremy Repanich, chef Alex Stupak compared the misuse of these techniques by less skilled chefs to “the pyrotechnics at a Kiss concert. Remove the flashy effects, and there’s nothing left.”

After becoming head chef at El Bulli, Adrià initiated a series of culinary workshops focused on menu innovation. The restaurant operated for six months each year, with the remaining six months dedicated to experimentation and refining new techniques. This blend of rigorous scientific exploration and creative freedom defined molecular gastronomy and earned El Bulli the title of Best Restaurant in the World by Restaurant Magazine five times during the 2000s.

The Trailblazing Chefs of Molecular Gastronomy

Meanwhile, a new generation of chefs was pushing culinary boundaries in their own kitchens. At The Fat Duck in Bray, England, British chef Heston Blumenthal—who attended the final two Erice workshops—brought a mad scientist approach to fine dining. His use of liquid nitrogen became one of his signature techniques.

With a boiling point of -321°F, liquid nitrogen enables chefs to freeze ingredients almost instantly. A common issue with frozen food is the formation of large ice crystals, which damage cellular structures and alter texture. Rapid freezing minimizes crystal size, preserving the food’s integrity. Blumenthal applied this concept to his Nitro-Poached Green Tea and Lime Mousse, a palate cleanser at The Fat Duck, flash-frozen right at the table.

Chef Wylie Dufresne. | Neilson Barnard/GettyImages

Chef Wylie Dufresne. | Neilson Barnard/GettyImagesAmerican chef Wylie Dufresne is another key figure in molecular gastronomy. At his now-closed New York restaurant wd~50, one standout dish was a deconstructed eggs benedict, featuring sous-vide egg yolks, delicate Canadian bacon, and fried hollandaise. Perfecting the fried hollandaise was particularly challenging; Dufresne’s team achieved it by incorporating gelatin for structure and starch to protect the egg yolks from scrambling under high heat.

Today, Dufresne channels his experimental spirit into running a doughnut shop and pop-up pizzeria in New York City. While these foods may seem simpler, they still reflect his scientific approach. From methylcellulose noodles to his once-signature “pizza pebbles,” Dufresne’s work remains rooted in food science. In 2021, he even delivered a lecture at Harvard on perfecting pizza dough, covering topics like gluten development, cold fermentation, and carbon dioxide manipulation.

Chef Grant Achatz. | Juan Naharro Gimenez/GettyImages

Chef Grant Achatz. | Juan Naharro Gimenez/GettyImagesGrant Achatz is another prominent American chef linked to molecular gastronomy. His Chicago restaurant Alinea showcases the fusion of chemistry and cuisine. The iconic translucent pumpkin pie is crafted by solidifying concentrated pumpkin pie stock in clear gelatin. Achatz also emphasizes the artistic dimension of molecular cooking, much like Carême did centuries ago. At Alinea, one dessert is painted directly onto the table, resembling an abstract artwork, while another features edible sugar balloons filled with helium, encouraging diners to inhale and playfully channel Carême’s imaginative pastry creations.

In a 2021 InsideHook article, Achatz highlighted the emotional aspect of molecular gastronomy, stating, “I describe this cooking style as using emotions as seasoning: intimidation, confusion, intrigue, happiness, magic, and nostalgia are layered over exquisite dishes through innovative techniques, ideas, and equipment that transform food in surprising ways.”

A Controversial Label

While these chefs are recognized for defining molecular gastronomy, not all of them accept the term. Some have openly dismissed it.

Heston Blumenthal told The Guardian, “The term ‘molecular’ implies complexity, and ‘gastronomy’ suggests elitism.” Ferran Adrià shares this view, preferring to call his culinary approach “deconstructivist.” Similarly, Grant Achatz describes his style as “progressive American.”

An olive-shaped, olive-flavored sphere. | Pam Susemiehl/Moment/Getty Images

An olive-shaped, olive-flavored sphere. | Pam Susemiehl/Moment/Getty ImagesAlternative terms like avant-garde, modernist, and experimental cuisine have been proposed to describe this science-driven approach to fine dining.

Despite various attempts, no alternative term has managed to replace molecular gastronomy in popular usage. While the phrase originated from a workshop unrelated to liquid olives or sugar balloons, and the term molecular may seem both too broad and too narrow, it remains fitting. Its futuristic tone highlights the essential role of science in crafting extraordinary flavors and the endless potential of culinary experimentation.

“Ingredients are fundamentally physical and chemical substances, and cooking transforms them from one state to another,” McGee explains. “These transformations are governed by the principles of physics and chemistry. Whether you’re cooking an egg or preparing a complex dish, you’re engaging in both physics and chemistry. The deeper our understanding of these processes, the more control we gain, allowing us to achieve the desired outcomes.”

The term may seem extravagant, but it mirrors the bold and occasionally polarizing nature of the dishes served at the most groundbreaking restaurants of the 2000s.