Among the many controversies that have angered politicians over the years, a peculiar one in 1981 drew sharp criticism: the issue of mold-covered cheese.

In 1981, Agriculture Secretary John Block displayed a block of mold-ridden processed cheese in the White House to highlight the dire consequences of dairy subsidies. “We can’t continue storing the oldest cheese indefinitely,” he remarked.

Tom Harkin, an Iowa congressman and staunch dairy supporter, expressed outrage. “It’s disgraceful,” he declared during a House discussion on agricultural legislation. “Secretary Block should be ashamed for showcasing spoiled cheese.”

The 1981 cheese controversy was a significant chapter in a broader dairy dilemma, sparking debates over government intervention and economic policies. This led to the storage of hundreds of millions of pounds of cheese in a secure underground facility in Missouri, buried 100 feet beneath the surface. The nation was undeniably facing a cheese emergency.

Under Fire for Cheese

To grasp why the government amassed such a vast cheese reserve, we must look back to 1977. That year, President Jimmy Carter decided to bolster the struggling dairy sector by injecting approximately $2 billion. Through the Commodity Credit Corporation (CCC), a longstanding federal initiative, the government was empowered to buy surplus dairy products. This allowed farmers to increase production without fear of losses, as any unsold goods would be purchased by the government.

Unsurprisingly, this led to a milk surplus, much of which was turned into cheese for its extended shelf life. As processed cheese stocks grew, the government found itself with a 500 million-pound surplus stored in warehouses, prompting Secretary Block’s dramatic presentation of moldy cheese.

One proposed solution was to discard the cheese into the ocean, but with many Americans facing hunger, this was seen as excessively wasteful. By this time, the issue had shifted from Carter’s administration to Ronald Reagan’s. Reagan introduced the Temporary Emergency Food Assistance Program, distributing the cheese to those in need. However, as Block had warned, the cheese was often spoiled, leading to the term “government cheese” becoming associated with poor quality and societal stigma.

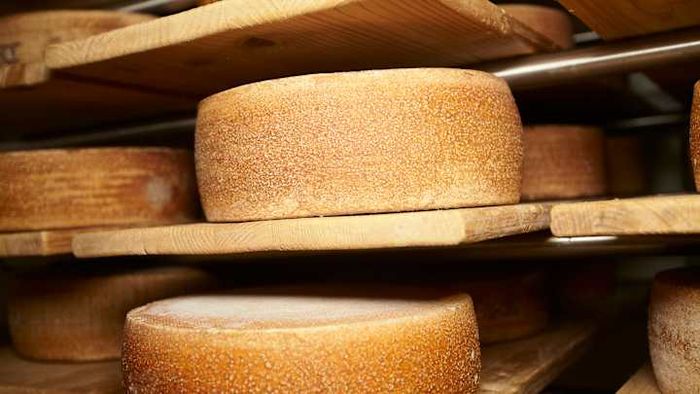

Even as the cheese was being redistributed, the Department of Agriculture still required storage solutions. This led to the utilization of cheese caves. While much of the cheese was kept in warehouses across various states, a network of limestone mines beneath Springfield, Missouri, became a primary storage site, housing the majority of the surplus. These caves maintained a natural temperature of around 60 degrees, reducing cooling costs, and provided millions of square feet of space, making them perfect for the government’s towering cheese stockpiles.

Springfield wasn’t the sole hub for cheese storage. By 1981, dairy surpluses—including cheese, butter, and powdered milk—were also hidden beneath Kansas City and other areas. Inside these caves, one could find 500-pound cheese barrels, 5-pound cheese loaves, and 50-pound sacks of dry milk. Kansas City alone stored a staggering 161 million pounds of dairy products.

Cheese Barrels

Cheese experts estimated that maintaining such vast reserves cost the government over $1 million daily. There was also urgency to speed up distribution, as storage expenses and the risk of spoilage created a pressing deadline. Additionally, storage capacity was limited, leaving America in the midst of a cheese crisis.

Facing criticism over the high costs, the government began reducing financial aid to farmers, though it couldn’t eliminate it completely. Compounding the issue, the CCC program allowed farmers to sell unlimited quantities at above-market rates, causing the cheese stockpile to balloon to roughly 1.2 billion pounds by 1984.

Marketing came to the rescue in the 1990s. The National Dairy Promotion and Research Board took on the challenge of reducing the cheese surplus by promoting cheesy fast-food options and launching the iconic Got Milk? campaign. While their efforts weren’t solely aimed at emptying cheese caves, dairy demand surged. This, along with reduced government subsidies, helped transform the overwhelming cheese surplus into a more manageable quantity.

Today, the government still purchases cheese, mainly to support school lunches and food assistance programs, but large-scale stockpiling is no longer common. The Missouri cheese caves remain, though the Department of Agriculture owns only a fraction of the 1.4 billion pounds of cheese stored underground nationwide. Most of their stock is reserved for military use.

Food companies like Kraft Heinz now rent these underground spaces for cheese storage and aging. This supports America’s massive cheese consumption, which totals around 1 billion pounds each year. Unless consumption habits change, these subterranean cheese vaults will likely remain in use for the foreseeable future.