1. Sample Essay 4

Nguyễn Du, one of the most renowned authors in Vietnamese literature, is often primarily associated with his famous work 'Truyện Kiều'. However, few people are aware that he also penned another significant piece, 'Đọc Tiểu Thanh Kí', which holds deep humanistic values akin to 'Truyện Kiều'.

West Lake, where the flowers once bloomed, now lies in ruins.

Looking out the window, I reminisce about the past with a single sheet of paper.

This opening verse is like a mournful sigh. The West Lake still exists, but the once-beautiful flower garden has now turned to desolation. What was once full of life and beauty has been replaced by decay and abandonment. The word 'tận' indicates absolute negation, meaning everything has been lost with no trace left behind. Nguyễn Du uses this imagery of the garden to contrast a golden past with the ruin of the present. It is a vivid representation of the rapidly changing world: 'The sea of life is but a fleeting dream,' where the poet sees the fragility of human existence. The single sheet of paper mentioned refers to Tiểu Thanh's poetic 'kí', a meager surviving testament to her story.

If the garden symbolizes a vanished era, this single sheet is the last vestige of a human life, a haunting presence from over three centuries ago (Tiểu Thanh died in 1492, and Nguyễn Du wept for her in 1813, over 300 years later).

Nguyễn Du's reflection on the transience of things and the loneliness of the human condition is poignant. The beauty of the world is destroyed by time, and he portrays this solitude not just in the dying evening light outside his window but also through the use of the words 'độc' and 'nhất'.

Two key lines:

Cosmetic beauty fades, leaving only sorrow after death.

Literary works have no destiny, they are left unfinished.

In the story of Tiểu Thanh, it is told that before her death, she commissioned an artist to paint her portrait. The first painting was criticized for lacking life, the second captured her spirit but looked rigid and forced. The third one was praised as it truly embodied her likeness and spirit, gentle and graceful. Tiểu Thanh hung the portrait and cried herself to death. When her husband arrived and saw the portrait, he mistook it for her still alive, feeling sorrow and mourning. But when the first wife presented the painting along with the poems, the husband only accepted the first one. This reveals the harsh reality of Tiểu Thanh's life—her beauty was only acknowledged after her death, and even her literary works were burned, leaving only a few surviving poems.

The deeper meaning of these lines suggests that despite being destroyed by dark forces, the beauty and talent of a person cannot be easily erased. There is an invisible law that ensures they endure, like a plant that continues to thrive. However, to survive, beauty and talent must endure great suffering and pain.

The first four lines outwardly express the story of Tiểu Thanh, but the next four lines shift inwardly, reflecting Nguyễn Du's own thoughts. He expresses sympathy and admiration for those gifted individuals whose lives are marred by hardship: 'How could beauty and talent bear such a miserable fate?' These next lines reflect Nguyễn Du's deep solitude as he contemplates his own life.

The two concluding lines:

What we regret from the past, we cannot blame on fate.

Those with talent are often cursed by a strange misfortune of life.

Here, 'regret' refers to a deep, enduring dissatisfaction that can never be fully understood or explained. It does not indicate hatred but sorrow for unresolvable past events. In Confucianism, one does not blame others or fate, so this is not a criticism of the heavens.

'Phong vận' (talent and fortune) refers to the harmonious expression of a person's talent and success. Yet, despite this, many people with talent experience mysterious and unjust misfortunes, impossible to explain by any natural laws. This phrase implies a deep empathy for those who are talented but cursed by fate.

Nguyễn Du, living centuries after Tiểu Thanh, felt a kinship with her suffering, which is why he wept for her. He pondered whether, when his time comes, anyone would mourn his death as he mourned hers: 'Today, I weep for you, but who will weep for me tomorrow?' He felt a deep uncertainty about the future, wondering if anyone would understand him as he understood the plight of Tiểu Thanh.

Nguyễn Du's lament reflects his own sense of impending obscurity, not knowing if future generations would appreciate his work. Yet, his genius has been recognized, and the Vietnamese people honor him as a national literary hero:

The voice of sorrow echoes through the heavens and the earth.

It sounds like the mountains and rivers crying out for eternity.

A thousand years later, Nguyễn Du will still be remembered.

His sorrowful voice is like a mother’s lullaby for her child.

(Tố Hữu - A tribute to Nguyễn Du)

Nguyễn Du's descendants mourned his passing, truly weeping for him, as they honored his legacy.

2. Reference Work No. 5

Nguyễn Du’s connection to Tiểu Thanh seems as fated as Thúy Kiều’s bond with Đạm Tiên. On Thanh Minh Day, why does spring’s vitality fail to reach Đạm Tiên’s grave on the mound of grass?

Grasses grow unevenly by the road,

The yellowing grass, a blend of yellow and green.

The yellowed grass amidst spring perfectly sets the scene for the meeting between two souls marked by tragedy. Nguyễn Du and Tiểu Thanh are separated not just by life and death, but by three centuries. Yet, despite such a vast gap, empathy and understanding transcend all. Nguyễn Du’s *Tiểu Thanh Ký* speaks from the heart, bridging all distances to offer sympathy for a life long lost.

The meeting between Nguyễn Du and Tiểu Thanh feels destined, a convergence of two gifted souls bound by literary fate:

The beauty of West Lake now turned into a barren mound,

Heartbroken, by the window, a torn piece of paper.

This scene paints a picture of desolation. Nguyễn Du refers to West Lake in the first line of the poem (located in Zhejiang, China), where Tiểu Thanh, a woman of both beauty and tragedy, once lived. This change feels like the inevitable progression of life’s hardships: an irreversible transformation from past beauty to present desolation, from a blooming garden to a barren mound, from existence to nothingness. The word *tẫn* in the original phrase “hoa uyển tẫn thành khư” invokes a sense of total and violent change, leaving no trace behind. The poem isn’t just about life’s fleeting nature but rather about the destruction of beauty. The verse paints the scene, but it stirs deep sorrow and brings to light the tragic story of Tiểu Thanh. It reflects personal grief and resonates with the shared experiences of humanity.

The true revelation of Nguyễn Du’s encounter with Tiểu Thanh is captured in the following verse:

Alone, at the window, I read a book

(Visiting her through a book, a fragment read at the window).

During her life, Tiểu Thanh wrote a collection of poems (the *Tiểu Thanh Ký*) to express her sorrow and loneliness. After her tragic death, her book was burned by her wife, leaving only a few remnants. So, Nguyễn Du’s mourning for Tiểu Thanh didn’t occur at Cô Sơn. His grief transcends both time and space, as he “visits” her only through the fragmented book. This poem continues to evoke her tragic fate, suggesting that the remnants of Tiểu Thanh’s book represent the fragments of her life—broken but not entirely lost, lingering with bitterness and unfulfilled resentment.

Tiểu Thanh, beautiful yet unfortunate, talented yet doomed. Is this the fate of those blessed with both beauty and talent? This sorrow haunted Nguyễn Du throughout his life:

Even buried makeup cannot quell the resentment,

Literary talent is cursed, still lingering in memory.

These lines succinctly capture Tiểu Thanh’s tragic story. Makeup represents the curse of beauty, while literature represents the curse of talent. Both are personified as having spirit and fate, embodying the essence of Tiểu Thanh. Though her book was destroyed, her life continues to haunt, crying out for those who share her fate. These verses evoke sorrow and admiration for both beauty and intellect.

The next four lines reveal a shift in Nguyễn Du’s perspective. From grieving one gifted woman, he extends his sorrow to all those similarly gifted and doomed. His grief for Tiểu Thanh transforms into sorrow for all talented souls:

Ancient and modern sorrows are beyond questioning,

The fate of the gifted traveler is their burden to bear.

This verse holds all the ancient and modern sorrow in a question that lingers in the air, unanswered. Why do those with beauty and talent suffer so? Why do the gifted often die young? The poem expresses human anguish, reflecting the recurring misfortunes of life: the talented and beautiful must endure suffering. The question itself seems to invite no answer, deepening the pain of the grievance.

Tiểu Thanh Ký also embodies Nguyễn Du’s lifelong torment. It reflects his anguish over the precariousness of human nature and the fleeting nature of life. This deep sorrow captures the despair of Nguyễn Du’s era.

3. Reference Work No. 1

Phùng Sinh, a wealthy and indulgent man from Hangzhou, Zhejiang, China, lived during the late Ming dynasty. One day, he traveled to Yangzhou (Jiangsu) and purchased a young girl named Tiểu Thanh, whose given name was Nguyên Nguyên. She came from the same family name, Phùng, and was taken as a concubine. Beautiful and highly intelligent from a young age, she excelled in poetry, music, and dance. At just sixteen, she was sold to Phùng Sinh. Upon seeing him, Tiểu Thanh immediately sensed her tragic future, lamenting:

My life is already over!

Phùng Sinh's first wife was notorious for her jealousy and cruelty, treating Tiểu Thanh horribly. Eventually, she was sent to live in isolation at the foot of Cô Sơn, near West Lake, beside the Tô Dyke, constructed by the famed poet and official Tô Đông Pha during the Song dynasty. She was forbidden from seeing Phùng Sinh. The surroundings were dreary, and the loneliness unbearable. In the solitude of her home, with only the wind through pine trees, the chimes of a distant temple, and a misty landscape, Tiểu Thanh spent her days in sorrow with only a few children and an elderly maidservant for company. Her resentment and sadness were expressed only through tears and poetry. Over time, these feelings worsened into illness.

During a particularly severe illness, Tiểu Thanh called for an artist to paint her portrait. The first portrait was unsatisfactory, so she said:

- This is only the image, not the spirit.

The second portrait was better but lacked vitality. She remarked, "It has spirit now, but the elegance is missing...". Finally, she was pleased with the third portrait.

She placed the final portrait on the table, surrounded by flowers and incense, and performed a self-sacrificial ceremony. She instructed her maid to write a farewell letter, ending with four poignant verses:

The silk thread snaps, tears fall like rain,

The ornate tower stands in vain, longing for a day,

As the evening sun tinges the peach blossom in a drunken hue,

There lies the spirit of a young girl, lost in her beauty.

She dropped the brush, leaned on the letter, and wept deeply before passing away.

After her death, Phùng Sinh's first wife continued her jealousy and had Tiểu Thanh's poems and portraits burned. Fortunately, one portrait, the second one, and some draft poems used for wrapping items for the maidservant’s daughter were spared.

Here are a couple of her remaining poems:

Spring comes, but the blood-stained tears blur,

Unfastening my robe, I twirl it around my neck,

Three hundred old plum trees,

Should turn into the tragic flowers of the camellia.

This poem expresses how the golden-yellow of plum blossoms transforms into the tragic red of camellia flowers.

Standing in front of the Buddha’s altar,

I wish not to be a drifting soul in the world,

Only to be a droplet of water,

To nourish the lotus, keeping it green for eternity.

This poem was written during a visit to the Heavenly Truc Temple at West Lake, contrasting the calm and humble approach of Tiểu Thanh to the boldness of poets like Nguyễn Công Trứ, who famously wrote, "In the next life, don’t be a human being! Be a pine tree standing alone in the sky, singing."

Her sadness had transformed into a compassionate wish, offering beauty and peace to others.

The cold rain falls, but I cannot hear its sound,

Lighting a lamp, I read stories of the past,

Life is filled with people who are naive and foolish,

But it is not just me who suffers from fate’s cruelty.

This poem was written on a stormy night, reflecting on *Mẫu Đơn Đình*, a famous Chinese opera about Lệ Nương, whose death left an unfulfilled longing and a love-driven obsession.

Many other poets also wrote about Tiểu Thanh. One such poet, Chử Hạc Sinh, visited her grave and wrote:

Silently, at the grave, who holds the green grass,

Lost in thought, tears of love and bitterness fall,

Who still reads *Mẫu Đơn Đình* these days?

The cold wind and sparse rain beat against the curtain.

One night, Hạc Sinh walked alone beneath the plum trees, still lost in thoughts of Tiểu Thanh’s fate. He imagined her graceful figure walking ahead of him, and he composed two additional poems. Here is one of them:

The moonlight shines on the plum garden at night,

I imagine a faint, elegant shadow moving,

How sorrowful the wind from the afternoon,

It bends the orchid and breaks the bamboo, mourning the loss.

4. Reference Work No. 2

Tiểu Thanh was a talented and beautiful woman who suffered the fate of being a concubine, enduring torment due to jealousy and dying young. Her poetry collection was burned by her first wife, leaving only a few remnants called 'The Remains.' Nguyễn Du read these poems, visited her, and mourned for her tragic life.

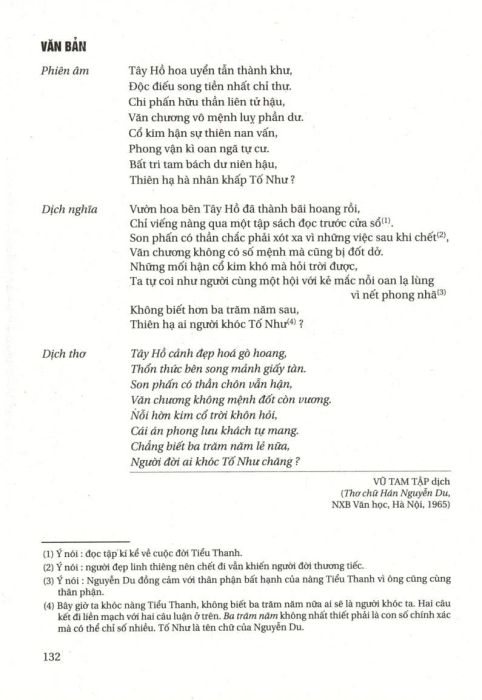

The poem *Độc Tiểu Thanh ký* expresses deep sympathy and sorrow for the fate of this gifted woman, who was oppressed and died in injustice. Nguyễn Du also reflects on his own tragic fate:

'The West Lake's flower garden has turned to ruin,'

'A lone poem sits beside the old window,'

'The powder of the past still lingers, after the lotus blooms,'

'Literature, too, is left with nothing but remnants.'

'The sorrow of the past and present, no one can truly question,'

'The wind and fortune's injustice, I carry it myself.'

'How will future generations understand,'

'Who in the world will weep for Tố Như?'

The beauty and talent that once were are now only a gravestone. But the life she led and the poetry she created moved Nguyễn Du deeply.

Nguyễn Du's verses about West Lake (in China) reflect how the once thriving place has withered into a forgotten past. West Lake, the inspiration for the poet, now stands as a desolate ruin. The poet's mood mirrors this melancholy sense of lost beauty. Amidst this nostalgic atmosphere, Nguyễn Du weeps for Tiểu Thanh through an old book left behind:

'West Lake’s beautiful scene has become a barren hill,'

'I weep by the old window, with remnants of paper.'

In these verses, Nguyễn Du praises Tiểu Thanh's beauty and talent:

'The powder has a spirit that endures beyond the lotus bloom,'

'Literature lacks fate, yet its legacy remains.'

Nguyễn Du held Tiểu Thanh in high regard, deeply moved by the fate of talented and beautiful people who were crushed by life. He felt that beauty could transcend time, as Tiểu Thanh’s image would live on through her poetic legacy, even though she had been wronged.

In the next verses, Nguyễn Du reflects on a larger, profound issue that goes beyond space and time:

'The sorrow of ancient and modern times is hard to answer,'

'The injustice of fortune, I must bear alone.'

Tiểu Thanh’s tragic fate becomes a timeless pain, elevated by Nguyễn Du to a universal suffering. From his perspective, this was a cruel, unchangeable rule of fate, one that left humanity powerless. Nguyễn Du deeply empathized with the plight of talented yet doomed people like Tiểu Thanh.

'Talent and fate are rivals' is an ancient belief. Beauty and talent often come with misfortune, a paradox that reflects the harsh realities of life. In *Truyện Kiều*, Nguyễn Du wrote:

'Alas, what a fate to share this mortal life,'

'What harm it is to carry beauty and talent.'

Through his reflections, Nguyễn Du expressed his own life’s sorrows, considering Tiểu Thanh’s tragic fate alongside his own. Tiểu Thanh, with her beauty and talent, was trapped by an unjust fate, dying young, and her works were left to wither, much like her life. Nguyễn Du wept not only for her but also for his own fate.

'The injustice of fortune, I must bear alone.'

'The injustice of fortune' is the strange fate of those with grace and elegance. Traits that should be celebrated by life often lead to harsh consequences. Like Tiểu Thanh, who died in the prime of youth, or Nguyễn Du, a poet with talent but no success, their fates mirror each other. This is the injustice of life—a feudal society unable to accept beauty and talent like Tiểu Thanh's, just as it could not accept Nguyễn Du.

5. Reference Work No. 3

The fate of women in the past was often fraught with hardship, and countless poems emerged to express the sorrow of such lives. Born with beauty and talent, but cursed by the saying 'a beauty has a tragic fate,' many women like Tiểu Thanh suffered through rejection, oppression, and even death. This is the life of Tiểu Thanh in Nguyễn Du's *Đọc Tiểu Thanh Ký*.

Tiểu Thanh was intelligent, beautiful, and virtuous, catching the eye of Phùng Sinh, a wealthy man with a love for indulgence. At just sixteen, she was brought into his household as a concubine. Yet, despite living in luxury, she found no joy, enduring the jealousy and mistreatment of the first wife. Life as a shared wife was never easy, and the first wife did everything she could to isolate Tiểu Thanh, sending her to live alone at Cô Sơn. In this lonely, desolate place, surrounded only by the wilderness and her poetry as a companion, Tiểu Thanh poured her sorrows, pain, and resentment into her verses. She passed away at just eighteen, living a short and sorrowful life. After her death, her poems were cruelly burned by the first wife, with only a few remnants preserved. Nguyễn Du wrote heartfelt verses mourning her life:

'The West Lake, once beautiful, now a barren hill,'

'I weep by the window with a fragment of paper.'

The beautiful scenery of West Lake, once admired for its vibrant flowers and pure air, now lay in ruins. The past beauty is gone, replaced only by decay. Is this not a reflection of Tiểu Thanh’s life? Her beauty and talent were celebrated by many, yet she suffered the injustices of being a concubine, ending her life in loneliness. The poet holds a piece of her poetry, perhaps the last trace of her pain and suffering, as a symbol of her tragic fate, which moved Nguyễn Du to tears.

'Though beauty may fade, its spirit lingers on,'

'Though literature may perish, its traces remain.'

Tiểu Thanh's life was filled with injustice, and even the seemingly imperceptible things—like her beauty and talent—hold an everlasting sense of sorrow. Even after her death, her beauty, character, and talents continue to live on through time, untouched by those who would try to erase them. There is something unbreakable in these qualities, something that cannot be destroyed, no matter how hard others try.

'The sorrow of the past and present cannot be questioned by heaven,'

'The fate of the beautiful soul, it is carried alone.'

Tiểu Thanh’s turbulent fate evokes profound sorrow, transcending centuries. The regret that accompanies her story still lingers, and it leaves us questioning: Why must such pure, talented individuals suffer so? Why are the gifted never truly appreciated? Does heaven hear the laments of those who endure such hardships?

This poem is Nguyễn Du's lament for Tiểu Thanh—one who lived a life full of unjust trials. It not only paints the image of a beautiful yet tragic soul but also highlights the poet’s deep empathy for human suffering and his profound humanitarian spirit.