Should the road to hell be built on noble intentions, it likely winds through the decaying corridors of Bethlem Hospital. Established in 1247 as a priory for the New Order of St. Mary of Bethlehem, the monks initially cared for the poor and mentally ill. Their approach involved strict discipline, minimal nourishment, and social isolation, believing these methods would suppress the troubled mind.

Though their intentions were virtuous, their successors lacked the same moral integrity. Over the next five centuries, the institution descended into chaos and filth. Bethlem became so notorious that its nickname, 'Bedlam,' became synonymous with madness worldwide.

10. The Beginnings

Initially, Bethlem was a modest establishment, housing only a few inmates at a time. The building was constructed over a sewer that often flooded, forcing patients to wade through the filthy water. It could hold about twelve patients simultaneously and included a kitchen and a yard for exercise.

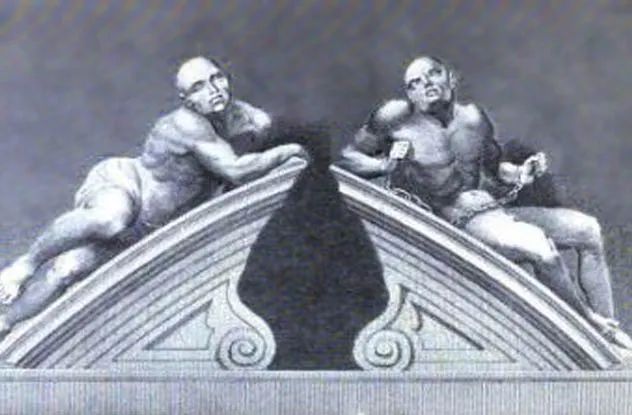

Details about Bedlam during the medieval era are scarce, but during this time, ownership shifted from the church to the English crown, likely due to the government's anticipation of financial gain. By the 1600s, the original building was in ruins. A new facility was constructed in the late 17th century, featuring a grand entrance adorned with two statues depicting human anguish: “Melancholy” and “Raving Madness.” Melancholy appears expressionless and empty, while Raving Madness is depicted in a state of frenzied rage, restrained by chains.

Many of the patients confined there did not fit modern definitions of mental illness. Alongside individuals with severe psychiatric conditions like schizophrenia and psychopathy were those with epilepsy and learning disabilities. These individuals were often abandoned by their families, leaving them vulnerable to widespread mistreatment.

9. Rotational Therapy

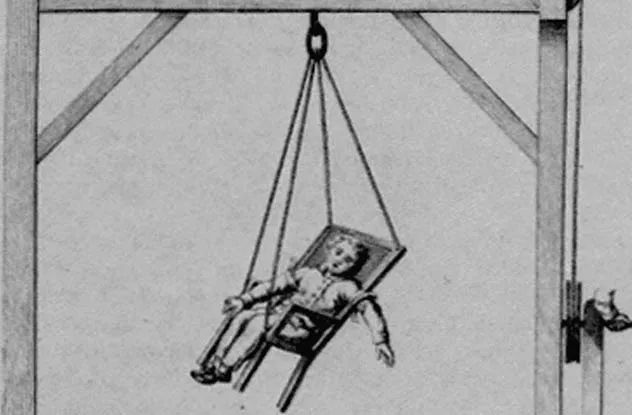

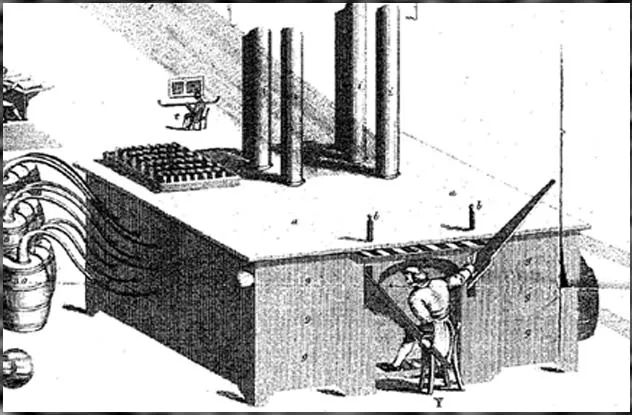

Among Bedlam's numerous contentious treatments, rotational therapy appears relatively harmless at first glance. Developed by Erasmus Darwin (Charles Darwin's grandfather), this method involved placing a patient in a chair or swing hanging from the ceiling. An orderly would then spin the chair, with the speed and duration determined by a physician.

This rudimentary amusement ride could whirl at an astonishing 100 rotations per minute. While carnival rides are enjoyable, their short duration makes them bearable. Two minutes of defying gravity is exhilarating—but imagine enduring such motion for hours on end.

Numerous patients at Bedlam endured this treatment. Inducing dizziness did nothing to alleviate mental illness. Side effects included nausea, paleness, and loss of bladder control. At the time, these reactions were deemed beneficial, particularly vomiting, which was thought to have healing properties. Interestingly, rotational therapy later offered significant insights to researchers studying vertigo and its impact on balance.

8. Famous Patients

Although most of Bedlam's patients remain nameless and forgotten by history, the asylum was home to a few notable individuals. Among them were Augustus Pugin, the architect behind the Palace of Westminster's interior (the meeting place of parliament), several would-be assassins of royalty, and the infamous pickpocket Mary Frith, also known as Moll Cutpurse.

One of the most extraordinary patients to walk Bedlam's halls was Daniel, a former porter for Oliver Cromwell. Standing at an astonishing 229 centimeters (7’6”), Daniel would have been a towering figure in the 17th century, when few men exceeded 6 feet in height. Cromwell ensured Daniel had his own personal library during his stay.

A devout religious enthusiast and purported clairvoyant, Daniel formed his own 'congregation' within Bedlam, where followers gathered to listen to his sermons. He was said to possess the ability to foresee the future, allegedly predicting several catastrophic events, such as a devastating plague and the Great Fire of London in 1666, which ravaged much of the city.

7. Art

There’s no denying the strong connection between art and mental illness; renowned artists like Edvard Munch, Vincent van Gogh, and Michelangelo all appeared to wrestle with inner demons that fueled their creativity. Similarly, Bedlam Hospital has played its role in inspiring artistic expression.

Bedlam is portrayed as the tragic downfall of Tom Rakewell in a series of 1730s paintings by William Hogarth. The collection, titled “Rake’s Progress,” follows Tom as he inherits wealth, squanders it on gambling and vice, and ultimately ends up sprawled on the floor of Bedlam. In the final painting, society women observe his plight while other patients endure their own torments.

English painter Richard Dadd spent 20 years as a Bedlam patient. Believed to suffer from paranoid schizophrenia, Dadd became convinced his father was the devil and murdered him in August 1843. He fled to France, plotting to assassinate the Austrian emperor and the Pope under the delusion that the Egyptian god Osiris commanded him. He was apprehended after attempting to assault a fellow passenger with a razor on a train.

Dadd’s magnum opus, “The Fairy Feller’s Master-Stroke,” was commissioned by Bedlam’s head steward, George Henry Haydon. The painting, which Dadd worked on for nine years before abandoning it unfinished, offers a glimpse into his troubled psyche. It blends fantasy with intricate baroque details, Shakespearean references, and elements of folklore. Over the years, it has inspired many, including Freddie Mercury of Queen, who wrote a song dedicated to the artwork.

6. Brutal Treatments

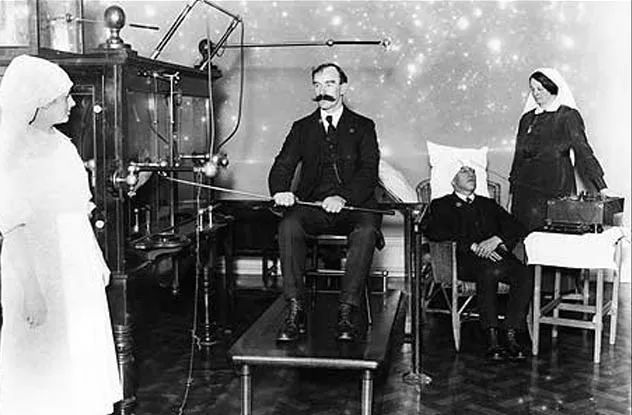

Psychiatric care has evolved significantly since Bedlam first began treating the mentally ill. Modern medicine offers effective pharmaceuticals and structured psychotherapy. However, in earlier times, treatments were often far more harrowing and physically damaging.

For over a century during the 18th and 19th centuries, Bedlam was managed by the Monro family of physicians. Patients endured harsh treatments, including cold water immersion, starvation, and physical abuse. In his 1811 work, “Dissertation on Insanity,” William Black described the asylum’s methods: “The strait waistcoat, when needed, and occasional purgatives are the main treatments. Nature, time, diet, confinement, and isolation from family are the primary supports.” He also detailed practices like venesection (an old term for bloodletting), leech therapy, cupping, and blistering.

Bedlam’s conditions were so appalling that it often turned away patients considered too weak to endure its brutal therapies. As early as 1758, figures like William Battie, M.D., who ran his own asylums, criticized Bedlam’s outdated practices and treatments.

5. Mass Graves

Many patients did not survive their time at Bedlam. Recent excavations for England’s Crossrail project uncovered mass graves in London, containing the remains of asylum residents and plague victims. Families often abandoned deceased patients, leading to their bodies being hastily buried without proper Christian rites. Hundreds of skeletons from Bedlam were found on Liverpool Street, a site destined to become a modern ticket hall. Before construction, 20 archaeological digs are required to meet planning regulations.

Many of the remains, dating back to the 16th century, are being examined at the Museum of London before reburial. Historical records mention a burial ground near the hospital, where the keeper was tasked with “smothering and repressing the stench” from decaying bodies. Among the discoveries is a nearly 2,000-year-old gold coin featuring Roman Emperor Hadrian.

4. Dissections

During the 18th and 19th centuries, anatomical research gained popularity across Europe. However, the scarcity of available corpses for dissection posed a significant challenge. Only the bodies of the poor and executed criminals were legally permitted for scientific study. This shortage fueled the macabre practice of “body snatching,” where graves were robbed to supply medical schools with cadavers.

In the late 1790s, Bryan Crowther joined Bedlam as its chief surgeon. While his primary role was to care for living patients, his true fascination lay with the deceased. Since families rarely claimed their dead relatives, Crowther had ample opportunity to dissect them. He focused particularly on studying the brain, hoping to uncover a physical cause for mental illness. Despite the illegality and moral outrage surrounding his actions, Crowther continued these experiments for nearly two decades.

3. Human Zoo

One of Bedlam’s most infamous features was its accessibility to the public. While visits from friends and family were expected, the asylum also functioned like a macabre attraction, where affluent visitors could pay a small fee to wander its foul-smelling corridors. These public tours became so popular that they contributed significantly to the hospital’s funding.

Exploring a mental institution was not without its dangers. While most patients posed little threat to others, some were violent psychopaths chained to the walls. Visitors also risked encountering unpredictable behavior, such as a distressed patient dumping the contents of a chamber pot from above.

In his 1771 work The Man of Feeling, Henry Mackenzie depicted a visit to the asylum: “Their guide took them first to the grim quarters of those suffering the most severe and untreatable madness. The rattling of chains, the piercing screams, and the curses shouted by some created an indescribably horrifying scene.”

2. Political Prisoners

Bedlam served purposes beyond treating mental illness. It was also a convenient tool for silencing political adversaries. Confining someone to an asylum not only removed them from the public eye but also tarnished their reputation, ensuring their credibility would be questioned even if they were eventually freed.

One of the most peculiar individuals in Bedlam’s history was James Tilly Matthews. During the tense period following the French Revolution, as England and France teetered on the brink of war, Matthews traveled to France independently, attempting to mediate the conflict. Suspected of espionage, he was imprisoned by the French. However, after several years, they concluded he was mentally unstable and sent him back to England. Upon his return, he accused Lord Liverpool, the British Home Secretary, of treason.

Matthews was confined to Bedlam, where he spun an extraordinary story. He claimed to be a secret agent whose mind was manipulated by the enigmatic “Air Loom Gang.” According to him, this group used a machine to control his thoughts via a magnet embedded in his brain, aiming to provoke a war with France. His family, convinced his delusions were internal, arranged for two doctors to evaluate him. Both declared him sane.

John Haslam, mentioned earlier, took a particular interest in Matthews, making him the focus of his influential work Illustrations of Madness. The book appeared to confirm Matthews’ insanity, dismissing any notion of political conspiracy. This case is widely regarded as the first fully documented instance of paranoid schizophrenia. Despite his delusions about the Air Loom, Matthews was highly intelligent and articulate. Some speculate that the stress of being manipulated by two governments drove him to madness.

1. Corruption

When Bedlam shifted from church control to the crown, corruption became inevitable. Much of this dishonesty involved embezzlement. Donations of food and supplies were often stolen or sold by staff, leaving patients severely underfed.

One of the darkest periods was under John Haslam, who became Bedlam’s head in 1795. Haslam believed mental illness could only be cured by breaking the patient’s will, achieved through various brutal methods. His reign ended after Quaker philanthropist Edward Wakefield visited in 1814. Aware of the appalling conditions and fearing public backlash, Bedlam staff attempted to block his entry, but Wakefield eventually gained access accompanied by a hospital governor and a member of Parliament.

Wakefield encountered shocking scenes, including naked, malnourished men chained to walls. The most extreme case was James Norris, restrained in a harness with chains leading to an adjacent room. Staff would pull the chains, slamming Norris into the wall. When asked how long this had occurred, Haslam admitted it had been 9 to 12 years. This sparked a public investigation into Bedlam’s practices. Haslam blamed chief surgeon Bryan Crowther for the conditions, but both were eventually dismissed, and the hospital began adopting more humane treatments.

In 1863, the Broadmoor Criminal Lunatic Asylum opened, taking in Bedlam’s most dangerous and notorious patients, including Richard Dadd. This marked a decline in Bedlam’s infamy, and today, it operates as Bethlem Royal Hospital.