A typographical symbol is essentially a printed representation of something—whether it’s a letter, number, or punctuation. The ? is referred to as the question mark; ( and ) are known as parentheses; and ; is the semicolon. You’re likely familiar with these already, but perhaps you're now curious about how one could extract 'fascinating' from the rather plain world of typography. It’s a valid question. Did you know the division sign actually has a name? Ever wondered about the origins of the paragraph sign? Or the history behind the % symbol? And why do Spanish speakers place inverted question marks at the start of their sentences? Keep reading to discover more!

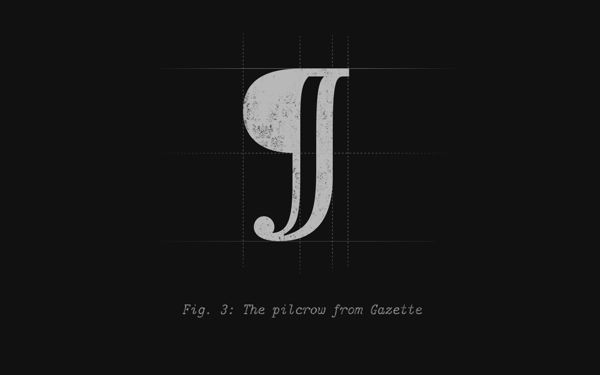

10. The Pilcrow—¶

The pilcrow, sometimes referred to as the 'paragraph mark,' has multiple functions, mainly to indicate the presence or position of a paragraph. It’s most often seen in word processors as a sign for a 'carriage return' or 'control character,' marking where a paragraph ends temporarily. The origin of the name is debated; while the Oxford English Dictionary traces it to a series of alterations of the word 'paragraph,' I prefer the Oxford Universal Dictionary’s theory, which suggests that the symbol resembles a crow without feathers—a 'pulled crow.' The mark itself derives from the letter C, which once stood for 'capitulum,' meaning 'chapter' in Latin. The two intersecting lines in the C likely serve as a writer's editorial note.

In the Middle Ages, the pilcrow was used in an earlier form to mark a new thought or idea before the paragraph became the standard method of doing so. Today, it has many uses, including in academic writing (when citing from an HTML page), legal documents (when referencing a specific paragraph), and in proofreading (to indicate when a paragraph needs to be split).

9. The Ampersand—&

The ampersand is a logogram representing the word 'and.' The symbol itself is derived from a shorthand version of the Latin word 'et,' and in certain fonts, like Adobe Caslon, the 'e' and 't' are clearly visible and connected. The word 'ampersand' has an interesting origin—it comes from the phrase 'and per se and,' which was a convoluted way of saying 'and by itself is just 'and.'' Confusing? That’s understandable. Essentially, it means that the symbol '&' stands alone to mean 'and.' So, where did this phrase originate? In the early 1800s, the ampersand was considered the 27th letter of the English alphabet, and since saying 'X, Y, Z, and' would be unclear, the phrase 'and per se and' was used instead. Over time, this phrase morphed into 'ampersand' by around 1837.

As is often the case with typographical marks, urban legends emerge. One such tale is that French physicist and mathematician André-Marie Ampère used the ampersand so frequently that it became known as 'Ampère’s and.' This, however, is simply not true. What we are left with is a charming little symbol that comes in many variations.

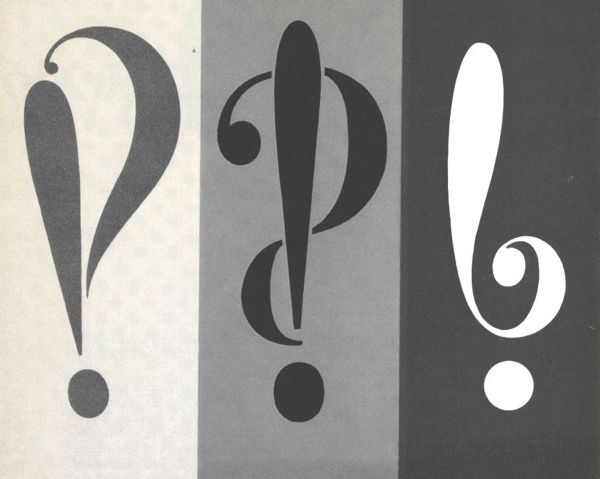

8. Interrobang—!?, ?!, or ‽

What?! You've never heard of the interrobang!? Really? Well, now you have, and all is forgiven. The interrobang is a unique punctuation mark, often considered part of the punctuation counterculture. It’s used at the end of sentences where you want both the excitement of an exclamation point and the curiosity of a question mark. While using both marks together had been common for a while, it wasn’t until 1962 that Martin K. Speckter, an advertising executive, had enough of the two marks and decided to create one symbol that could do the job of both. After soliciting name suggestions, rejecting fun options like 'rhet,' 'exclarotive,' and 'exclamaquest,' he coined the term interrobang, blending 'interro,' the Latin root for 'question' (as in 'interrogate'), and 'bang,' printer’s slang for the exclamation mark. The interrobang can refer to the combination of the two marks (!? or ?!), or the merged symbol itself (?).

7. At Sign—@

A couple of fun facts:

– The Spanish arroba was once a unit of weight equivalent to 25 pounds. – In other languages, the @ symbol is often referred to by names that liken it to an animal. For example: 'apenstaartje' (Dutch for 'monkey’s tail'); 'papacy' (Greek for 'little duck'); 'dalphaengi' (Korean for 'snail'); 'sobachka' (Russian for 'little dog').

6. Guillemets—« »

Guillemets are the French alternative to quotation marks. Not only are they physically different, but they also serve a distinct purpose—typically, guillemets are used to open and close entire conversations or exchanges, rather than individual remarks. Interestingly, the guillemet is named after a French printer, Guillaume Le Bé, who lived in the 16th century; 'Guillemet' is simply a diminutive of 'Guillaume.' One might imagine that French speakers refer to our quotation marks as 'Willies,' 'li’l Bills,' or 'Mini Williams.'

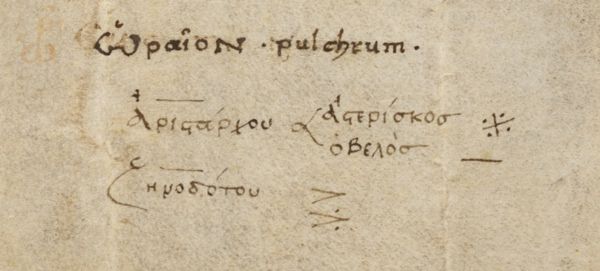

5. Obelus—÷

The Obelus, commonly known as the 'division sign,' has its origins in an Ancient Greek word for a sharpened point or stick-like object. The symbol shares its roots with the word 'obelisk.' In ancient times, the obelus was used to mark sections of text deemed erroneous or dubious—a tool that could have been quite handy for Wikipedia editors. It was first used to represent division in 1659 by Swiss mathematician Johann Rahn. While it remains common in the US and the UK, the obelus is not as widely used to indicate division in most other parts of the world.

4. Inverted ? and !—¿ and ¡

In Spanish, sentences that end with a question mark or exclamation point are also introduced by an inverted version of those marks. ¿Porque? Well, let me explain. Back in 1754, the Spanish Royal Academy identified a problem in the Spanish language: when you begin reading a sentence, it’s not immediately clear if it's a question or not until you reach the end.

Take the sentence, ¿vas a ir a la tienda? (Are you going to the store?). Until you hit the question mark, you’re left guessing—could it be a question or simply a statement saying 'you are going to the store'? In English, we have methods to signal when a question is coming, helping with both tone and comprehension. Before the Royal Academy's reforms, Spanish relied on context for these cues. They also decided that the exclamation point needed its own inverted version.

Although the shift was slow, the inverted marks are now an established feature of Spanish. Here are a few fun facts about their usage:

– Short and clear questions sometimes omit the inverted mark—Quien eres? – In digital communication, the inverted marks are often left out (emails, texting, etc.). – Some authors still refuse to use inverted marks. – Writers sometimes play with punctuation, such as starting a sentence with a ¡ and ending it with a ?. – The ¿ can appear in the middle of a sentence when only the final clause is a question. – Keep in mind that the ¿ and ¡ hang below the line, unlike the standard ? and !.

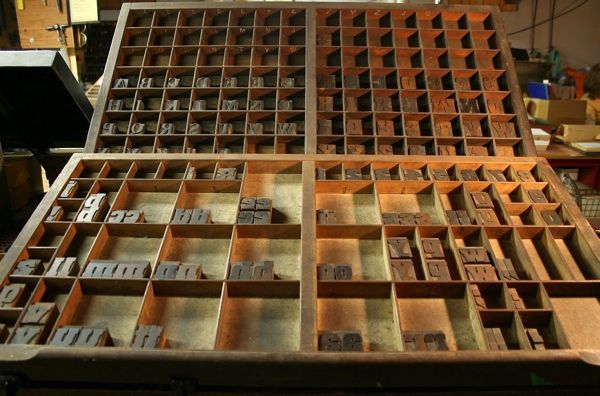

3. Upper Case and Lower Case Letters

Once I discovered the origins of the terms 'upper case' and 'lower case,' everything seemed so clear. I wondered: do others already know this? What other secrets are my friends and family hiding from me? In the end, I convinced myself that many of the readers of Mytourrs were just as clueless as I was, too embarrassed to speak up. Take heart, dear readers, for your ignorance can remain anonymous.

In the early days of printing, each letter was individually placed, and these letters were stored in 'cases.' The capital letters were stored in the 'upper case,' which was harder for printers to access since capital letters were used far less often. On the other hand, the lower case letters were kept in the 'lower case,' more easily accessible for the printer. This practice, simple as it is, dates back to 1588.

Here are some fun facts about cases: – A language that uses two cases is known as 'bicameral script.' On the other hand, languages that only use one case are referred to as 'unicase.' – But what were lowercase letters called before the invention of cases? They were known by different terms—Uppercase letters are called majuscules (or capitals), and lowercase letters are called minuscule. Pay attention to the spelling difference, especially with 'minuscule.'

2. Percent Sign—%

Observe the percent sign. Take note of its three distinct elements—a circle, a line, and another circle. Does it evoke anything in your mind? Could it, perhaps, be a familiar number, with its digits rearranged and aligned in a new way? A number of great importance, perhaps . . . the number 100?

The % symbol, naturally, indicates that the number it precedes should be understood as being divided by one hundred—'per cent.' The slash used to be horizontal, with zeroes placed above and below, but over time it became slanted, eventually leading to the form that D.E. Smith referred to in 1925 as the 'solidus form' of the percent sign. The solidus, also known as a slash, virgule, fraction bar, and several other names, looks like this: /.

As is the case with many things, there is disagreement about how to use the % symbol. Should there be a space between the number and the % sign? Should it be written as 'per cent' or 'percent'? And when should you use the % symbol, and when should you spell out the word?

1. Ditto mark

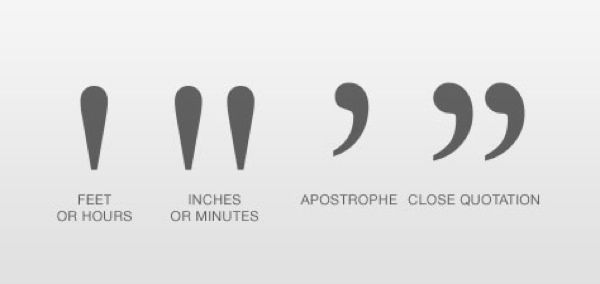

This one falls under 'common things we use all the time without knowing their name.' Ditto marks are those quotation-like symbols that save your wrist from a few more seconds of writing, signifying that the content directly above should be repeated. Although I once believed (as I, before my research, did) that the term 'ditto' might have been derived from the Latin root 'di' (meaning 'two', as in 'ditto' meaning 'me too!'), the truth is it comes from an early 1620s form of the Italian word for 'to say.' Originally, ditto marks were used to avoid redundant writing, especially when listing multiple dates within the same month.

A 'ditto mark' is a type of 'iteration mark.' Other languages have their own versions, like Chinese, Japanese, and Ancient Egyptian. It’s interesting to think about why Ancient Egyptian scribes might have needed a shorthand to reduce the effort of carving intricate images into stone.