While numerous toy fads emerged in the 20th century, none sparked the same level of chaos as the 1983 launch of Cabbage Patch Kids. Despite being mass-produced, each doll was uniquely designed with distinct hair, freckles, and facial features, thanks to computer sorting. The demand was so intense that shoppers often put themselves in harm's way to secure one: A 1983 Wall Street Journal editorial claimed that more Americans were preoccupied with acquiring a Kid than fearing nuclear war during the Cold War.

A new documentary, Billion Dollar Babies, exploring the phenomenon of these beloved dolls, is now available on Amazon Prime. Before tuning in, discover these 10 fascinating facts about Cabbage Patch Kids.

Initially, they were known as 'Little People.'

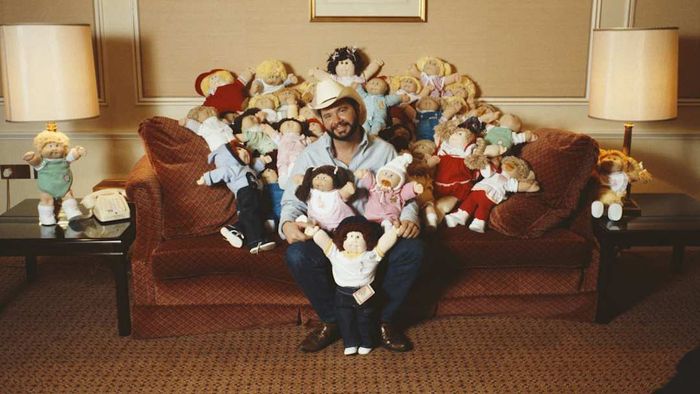

Xavier Roberts, the Creator of Cabbage Patch Dolls. | Bryn Colton/GettyImages

Xavier Roberts, the Creator of Cabbage Patch Dolls. | Bryn Colton/GettyImagesIn 1977, Xavier Roberts, an artist from Appalachia, started making soft-sculpture babies by hand in Georgia. He named them Little People and devised a unique marketing strategy where they weren’t sold but “adopted.” Roberts insisted they be called “babies” or “kids” rather than dolls. This imaginative approach was a hit, and he sold over 200,000 Little People before partnering with Coleco in 1982 to mass-produce them. With the help of advertising expert Roger Schlaifer, they were renamed Cabbage Patch Kids, inspired by the playful notion that babies come from “the cabbage patch.”

Shoppers were injured in the rush to purchase them.

The allure of Cabbage Patch Kids, despite their unconventional appearance, remains a mystery. Some psychologists suggested that the adoption narrative resonated with children who wanted to nurture, while others believed parents felt validated by securing a Kid for their children. Regardless, the 1983 holiday season saw unprecedented chaos. Limited stock led to stampedes in stores, with shoppers suffering injuries, broken bones, and even attempting to bribe staff. One store manager had to use a baseball bat to manage the unruly crowds.

Xavier Roberts appointed one Kid as chairman of the board.

As the head of Original Appalachian Artworks (OAA), established in 1978 to manufacture the dolls, Roberts delighted in maintaining the illusion that the Kids were real individuals. Otis Lee, one of his early creations, was designated chairman of the board and often accompanied Roberts, rarely being apart from him.

In a bid to secure a Cabbage Patch Kid, one parent went as far as flying to London.

Hug this Cabbage Patch Kid! | Bryn Colton/GettyImages

Hug this Cabbage Patch Kid! | Bryn Colton/GettyImagesEd Pennington, a mailman from Kansas City, frustrated by the shortage of Cabbage Patch Kids in North America, flew to London in 1983 to get one for his daughter, Leana. (Demand in England was lower, so there was no need for such extreme measures.) He purchased five Kids and donated four to charity.

Coleco had to stop advertising Cabbage Patch Kids due to overwhelming demand.

As demand for the Kids led to violent incidents, Coleco faced criticism for what consumer advocates called “false advertising.” James Picken, Nassau County’s consumer affairs commissioner, argued that the ads were “harassing small children” by promoting a product they couldn’t supply. Coleco eventually halted their TV ads, but the constant media coverage provided free publicity.

Adoption organizations were not supportive.

The marketing strategy for the Kids, which included an “oath” to care for them, a birth certificate, and adoption papers, appealed to children but drew criticism from adoption groups. They felt the toy minimized the experiences of real adoptive families and worried it might lead children to think people could be “purchased.”

Spotting a fake Cabbage Patch Kid was surprisingly simple.

The popularity of the Kids led to a flood of knockoff products. Consumer groups warned that counterfeit versions often had a strong, oily odor because they were stuffed with industrial rags. Buyers were advised to steer clear of Kids that smelled like kerosene, as these were considered highly flammable.

They took legal action against the Garbage Pail Kids.

Roberts and OAA were not amused when Topps introduced their Garbage Pail Kids trading cards in 1985. The cards, featuring characters with similar round heads and expressions to the Cabbage Patch Kids, were accused of copyright infringement. Following a legal dispute, Topps agreed to change the card designs.

One version of the doll had to be recalled for chewing on children’s hair.

Cabbage Patch fever peaked in 1984, with Coleco selling 20 million dolls before demand started to decline. To revive sales in the 1990s, Mattel, the new licensee, introduced Snack Time Kids, designed to “eat” fake French fries. However, the mechanism also grabbed and chewed on children’s long hair, leading to complaints and even a 911 call in Connecticut. Mattel eventually issued refunds and pulled the product from shelves.

Cabbage Patch Kids sparked a dark urban myth.

Doll hospitals could fix Cabbage Patch Kids damaged by pets, siblings, or accidents. However, a grim rumor circulated in newspapers: If a Kid was irreparable, Coleco would allegedly issue a death certificate for the doll.