Throughout history, one of the most chilling and fascinating practices has been the obsession with preserving the faces of the deceased. This tradition, known as creating a death mask, involves making a cast of the person's face after their passing, typically using materials like wax, clay, or plaster. Death masks have been a part of human culture for centuries, serving as a way to remember the departed. In modern times, they are crucial in the reconstruction of lost historical figures' faces and even offer insights into diseases and conditions that may have contributed to their deaths. With such a deep connection to history, it’s no wonder that these masks often stir up debates about their authenticity and significance.

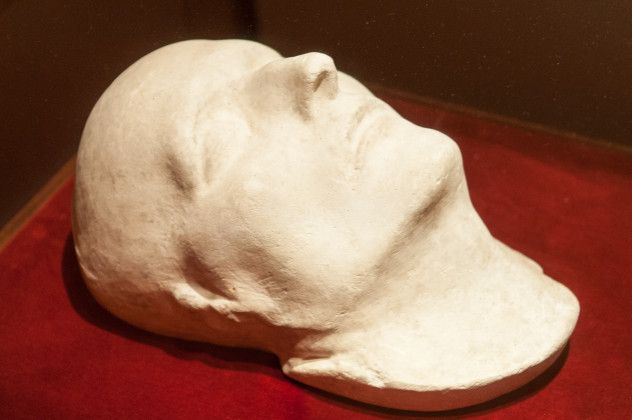

10. Napoleon Bonaparte

The mystery surrounding Napoleon Bonaparte’s death mask is as intriguing as the man himself. Napoleon passed away at the age of 51 on May 5, 1821, on the island of St. Helena. This much is undisputed. Two days following his death, a death mask was created by Dr. Francis Burton, with Dr. Antommarchi overseeing the process. This initial cast became the mold for the remaining three that are known to exist today.

Soon after the mask was made, it was reportedly stolen by a woman named Madame Bertrand, who smuggled it to England. After years of attempting to have it returned, Madame Bertrand finally gave Dr. Antommarchi a replica, which he confirmed as authentic based on his own recollection.

Here lies the issue: many question the authenticity of the returned mask. Dubbed the Antommarchi mask, it appeared to differ in proportion from the features depicted in paintings of Napoleon. Speculation spread that the cast might not have belonged to Napoleon at all, but rather his valet, Jean-Baptiste Cipriani.

The confusion was further fueled by rumors suggesting that the bones of Jean-Baptiste Cipriani, not Napoleon, were placed in the Emperor’s tomb at Les Invalides. Despite the swirling rumors, the Antommarchi mask remains the official mask displayed at Napoleon’s tomb in Paris. The other known versions of Napoleon’s death mask have traveled the world, sold at private auctions, and are now housed in various museums, but all trace back to Dr. Antommarchi’s original cast as the point of origin.

Is it authentic? The four existing death masks of Napoleon Bonaparte have been the subject of debate for over two centuries. However, it seems the prevailing belief is that these masks indeed depict the face of the infamous Emperor and not that of Jean-Baptiste Cipriani, as some conspiracy theorists argue. The mystery of their true origin may never be fully resolved, and this enigma is likely to endure for many more years to come.

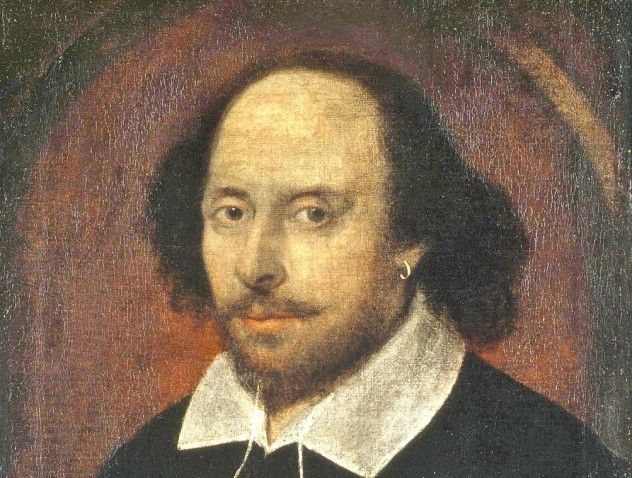

9. William Shakespeare

In 1842, a mask with an eerie resemblance to William Shakespeare was uncovered in a ragpicker’s shop in Germany. To add to the mystery, the year 1616—the year of Shakespeare’s death—was etched into the plaster. Since the mask’s discovery, it has been subjected to multiple analyses in an attempt to confirm if it truly represents Shakespeare’s likeness. Scholars and forensic scientists have relied on six distinct portraits, his funeral bust in Stratford-Upon-Avon, and the Davenant bust in London as the only evidence available.

Numerous studies have been conducted by comparing the features from the busts with those of the portraits and the mask. While the forehead and nose show striking similarities, it wasn’t until researchers examined the eyes that the evidence began to support the mask’s authenticity.

In a breakthrough forensic analysis, Professor Hildegard Hammerschmidt-Hummel of the University of Mainz discovered a swelling on Shakespeare’s left eyelid, a feature visible in the death mask, as well as the Chandos and Flower portraits, and the Davenant bust. The growth on the eyelid and the swelling near the nasal corner suggested that Shakespeare might have suffered from a rare cancer known as Mikulicz’s syndrome.

Hammerschmidt-Hummel’s research faced criticism from many art historians, particularly because the Flower portrait and Davenant bust are believed to have been created in the mid-19th century, centuries after Shakespeare’s death. The Chandos portrait is likely a contemporary likeness of Shakespeare, the Flower portrait is almost certainly a 19th-century forgery, and the Davenant bust is probably from the same period as well. Despite the evidence suggesting the death mask’s authenticity, many experts still regard the cast as a counterfeit.

Is it genuine? We may never know for certain. Just like many aspects of the Bard’s life, the true origins of his death mask remain shrouded in mystery.

8. Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart

The death of Mozart has been surrounded by mystery since the 18th century, and the death mask believed to be his has entered the realm of legend. It is said that the mask was created by Count Joseph Deym von Stritetz shortly after Mozart’s passing. The Count displayed it in his gallery, and upon his death, his widow continued to showcase it until her own death in 1821, when the mask mysteriously disappeared. Over the following 126 years, various conflicting accounts surfaced regarding the mask’s fate. Some claimed it was smashed by Mozart’s wife, while others said it was accidentally destroyed by a fan.

In 1947, a bronze version of the mask—likely a replica of the original—was found in an antique shop. Owner Willy Kauer noticed the striking resemblance to Mozart in the mask and, a year later, contacted the Austrian Ministry of Education to question its authenticity. After examining the mask, the ministry found only a few features that matched Mozart’s portraits, but the results were inconclusive.

In 1956, the Mozarteum conducted another examination of the mask, this time focusing on chemical tests to determine its age. The mask was thought to have been made sometime between 1830 and 1869. However, these tests also failed to provide a definitive answer, and the mystery surrounding the mask persisted. Eventually, Kauer passed the mask to Dr. Gunther Duda, who firmly believed it was Mozart’s, but its current location is now unknown.

Is it authentic? It’s likely that the mask is not real, even if it still exists somewhere in the world today. Nearly all the artifacts associated with Mozart’s death seem either fake or enveloped in mystery. Recall the tale of his

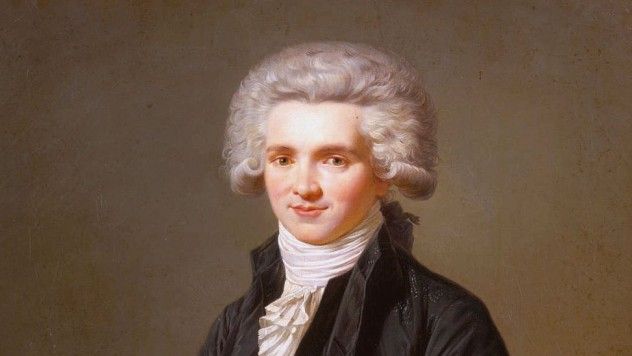

7. Maximilien Robespierre

During the height of the French Reign of Terror, Maximilien Robespierre met his end at the guillotine on July 28, 1794, at just 36 years old. Marie Tussaud was tasked with crafting death masks of the notorious figures who met their demise during the French Revolution, and Robespierre was at the top of her list. His original wax death mask is displayed in Madame Tussauds in London, with copies located at the Granet Museum in Aix-en-Provence and the National Museum of Natural History in Paris.

The authenticity of the mask was questioned after a terrifying facial reconstruction was made in 2013. The reconstructed face exhibited numerous anomalies and scars that matched descriptions of Robespierre’s features and possible ailments, such as pox scars, infections, nosebleeds, impaired vision, jaundice, extreme weakness, and twitching eyes and mouth. A diagnosis suggested he may have suffered from a rare autoimmune disease known as sarcoidosis.

Given the similarities between the reconstructed face and the symptoms, many believed the mask to be Robespierre’s. However, some historians argue that Madame Tussaud may have fabricated the authenticity of the mask to either enhance her business or protect herself from meeting the same fate as her subjects.

Moreover, the reconstructed face can’t be Robespierre’s, as it significantly deviates from his known portraits and fails to account for the severe jaw injury he sustained in a failed suicide attempt just a day before his execution.

Is it real? The truth remains uncertain, as the mask’s authenticity rests entirely on Madame Tussaud’s testimony. It’s likely not real, especially since the shattered jaw would have been a major detail in the original mask. One thing is certain though: the face of whoever the reconstructed mask belongs to is one of the most unnerving in history.

6. Dante Alighieri

In the space between the Apartments of Eleanor and the Halls of Priors in the Palazzo Vecchio, one object rests in isolation beneath glass. This object is said to be the death mask of Dante Alighieri—though the authenticity is debated. For centuries, this mask (often called the Kirkup mask) was believed to be a genuine likeness of the poet, cast directly from his face after his death. However, more recent research suggests that the mask was actually created in 1483 by Pietro and Tullio Lombardo, a full 162 years after Dante’s passing.

It is also believed that the mask might be a representation of a now-lost effigy from Dante’s tomb in Ravenna. The mask, surrounded by controversy, was gifted to the Palazzo Vecchio in 1911, where it continues to be displayed as a tribute to Dante’s immense impact on Florence. In 2007, a team of Italian scientists reconstructed Dante’s face, not by using the Kirkup mask, but instead based on measurements taken from Dante’s skull by Professor Fabio Frassetto in 1921. Frassetto was believed to have illegally broken into Dante’s crypt to extract the skull, which he then used to create a plaster cast.

Is it real? It has been determined that the Kirkup mask is unlikely to be the actual death mask of the famous poet. Instead, it is probably a likeness created many years after Dante’s death. As for the face reconstruction, it remains uncertain whether it truly represents Dante, as the bones in question have not been definitively proven to belong to him.

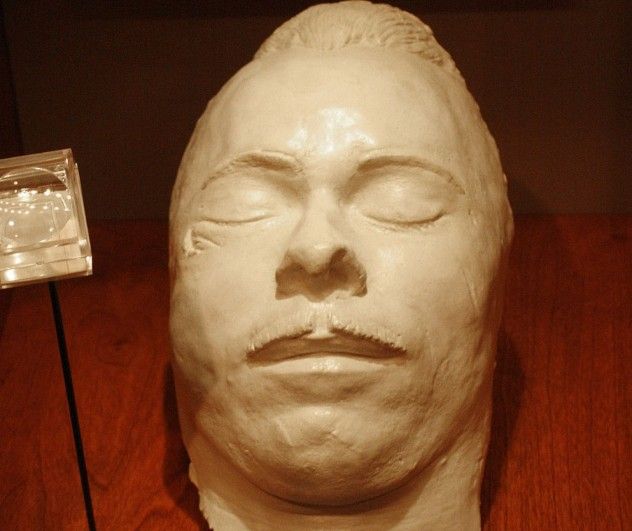

5. John Dillinger

Conspiracy theories have surrounded John Dillinger’s death ever since he was gunned down outside the Biograph Theater in Chicago. Every detail, from the night of his shooting to the specifics of his funeral, has been scrutinized to determine whether or not Dillinger masterminded the greatest heist in history. Eyewitnesses at the scene claimed the man who was shot had brown eyes, while Dillinger’s were known to be gray.

Further speculation arose when it was revealed that John Dillinger’s father and sister did not immediately recognize the body on the slab as belonging to him. One of the reasons for this uncertainty is that Dillinger had undergone several plastic surgeries before his death to alter his appearance and avoid being easily identified in public. These surgeries even included changes to his fingerprints, which may have been altered or removed entirely for identification purposes.

This naturally caused some confusion over whether the man who was killed was truly the infamous gangster. It’s generally accepted that the person shot was indeed John Dillinger, and his death mask provides a rare look at the face that stirred so much controversy. Despite his plastic surgeries, the mask bears a remarkable resemblance to the notorious gangster and has become a symbol of the Prohibition era and the violent outlaw culture associated with it.

Is it real? There’s no doubt that the death mask on display is genuine and has been authenticated. The real controversy, however, lies in whether or not the man killed was actually John Dillinger. While the mask and the body most likely belong to Public Enemy Number One, conspiracy theorists continue to raise questions.

4. Marie Antoinette

During the height of the French Revolution, Marie Tussaud wasn’t just tasked with creating a mask of Maximilien Robespierre. Two of the other heads that helped establish her fame belonged to the executed monarchs, King Louis XVI and Queen Marie Antoinette. It’s believed that Tussaud was compelled to cast their heads shortly after their deaths at the guillotine.

Marie Antoinette’s wax death mask is still on display at Madame Tussauds in London. The question of whether it is authentic is hardly a topic of debate, as it’s generally known that Tussaud herself created the cast of the queen’s head. The true controversy stems from the fact that the wax mask is the only surviving relic of the queen’s execution. No records exist of a plaster or clay mold from which the wax mask was created, and no other copies of the original are known to exist outside of the museum.

Some even find fault with the details of the original mask. It appears that Tussaud may have made certain adjustments, particularly when it comes to the ears. Wax, being a delicate medium, can crack when external features are added, so this is not an uncommon technique in the craft. Nonetheless, it remains the only known death mask of Marie Antoinette that still exists today.

Is it real? Given that Madame Tussaud is said to have obtained the actual guillotine that beheaded Marie Antoinette, it seems reasonable to assume that the wax death mask is also authentic. It has long been accepted that the wax head on display in London indeed belongs to the executed French queen.

3. Agamemnon

In 1876, Heinrich Schliemann made a groundbreaking discovery at an ancient burial site in Mycenae. While exploring the grave, he unearthed several bodies, five of which had been given death masks crafted entirely from gold. One mask, in particular, stood out due to its exceptional three-dimensional design and the remarkable detail given to the features.

Schliemann was thoroughly convinced that he had uncovered the tomb of Agamemnon, the legendary leader of the Greek forces during the Siege of Troy, as depicted in The Iliad. He justified his belief by pointing out that the other men found at the site were buried with weapons, implying they were warriors, whereas Agamemnon would have been an important figure worthy of such a mask.

The ornate golden mask seemed to symbolize immense wealth and high status, aligning with the tales of Agamemnon’s grandeur. However, there are many skeptics who challenge the authenticity of the mask. Archaeologists have conducted thorough investigations, concluding that the mask likely dates back to around 1550–1500 B.C., a period that predates Agamemnon’s supposed existence.

Additionally, Schliemann had a reputation for compromising his own excavations by planting artifacts in the dig site to serve his personal interests. Regardless of the controversy or the true identity of the mask’s owner, it is currently displayed at the National Archaeological Museum in Athens, Greece.

Is it real? The Mask of Agamemnon is undoubtedly an ancient artifact and death mask from some long-dead legend. But does it truly belong to Agamemnon? Science says no, but it certainly made for an interesting theory while it lasted.

2. Heinrich Himmler

Heinrich Himmler, leader of the Nazi Party, ended his life on May 23, 1945, by ingesting a cyanide capsule to avoid facing war crimes charges. Following his death, British intelligence officers created two death masks as proof of death.

One mask displayed a twisted, contorted face, while the other appeared peaceful and serene. The fate of the twisted mask remains unknown, but the more serene one is currently displayed at the Imperial War Museum in London. Himmler’s body was buried in an unmarked grave, and its location remains a mystery to this day. This uncertainty has fueled conspiracy theories surrounding the authenticity of the displayed mask and the fate of the first one. Despite these theories, the mask bears a striking resemblance to Himmler, leading many to believe it is indeed a cast of his face.

Is it real? It is widely accepted that the death mask is genuinely Himmler’s. While conspiracy theorists argue due to the mysterious disappearance of his body, it’s generally safe to assume the mask is indeed that of the deceased Reichsfuhrer.

1. Mary, Queen Of Scots

In 1587, Queen Elizabeth I sentenced her cousin, Mary, Queen of Scots, to death for treason. Mary was executed by beheading, which required three strikes to complete. As per tradition, a death mask was made immediately after her execution. There are two verified copies of this mask in the United Kingdom, although four were said to have been made. One of these masks is kept at Falkland Palace, based on the effigy of Mary found at Westminster Abbey.

The Lennoxlove mask is small in size and is widely believed to be the original. It has been in the possession of the Hamilton family for more than 250 years. Additional proof includes the fact that the Hamilton family also holds Mary’s jewelry, strengthening the case for the authenticity of this mask.

A second mask was discovered by Dr. Charles Hepburn in Peterborough, the original burial site of Mary. This hand-painted mask looks distinctly different from the Lennoxlove version. It is now on display in a museum dedicated to Mary in Jedburgh, a place believed to have been where she stayed while ill.

The authenticity of the mask is frequently questioned because its features do not match those of the Lennoxlove mask or many of Mary’s portraits. However, both masks are treated as genuine and are exhibited as such.

Is it real? The death mask at Lennoxlove is likely authentic, but certainty remains elusive. Documentation suggests the mask was created immediately following Mary’s execution, although the eyelashes were added later. As for the intricately painted wax head in Jedburgh, it appears significant artistic liberties were taken in its creation, and it’s unclear if it even depicts Mary at all.