If you were tasked with drawing a typical French person, you'd likely sketch someone with a mustache, a Gitane or Gauloise cigarette hanging from their lips. The figure would probably be on a bicycle, with a baguette and perhaps a croissant in a wicker basket on the front. There might be an accordion and a painting easel in the scene, accompanied by a little French poodle at the person’s side.

But how much of this imagined depiction is truly French, and how much is actually borrowed from elsewhere? This list will reveal that many things often linked with France actually have their origins elsewhere.

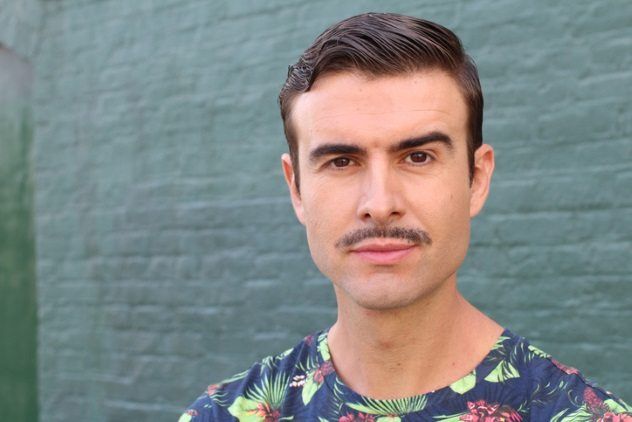

10. The Mustache

Not unexpectedly, the mustache is a foreign trend. A cave painting from 300 BC, depicting a Scythian warrior with a meticulously styled mustache, is commonly recognized as the earliest example of the trend. However, even older Egyptian artifacts, some dating back to 2650 BC, feature similar mustaches on men depicted on pottery and other items. The mustache was popular in ancient Egypt until 1800 BC, when the ruling pharaoh prohibited the growth of facial hair above the lip.

From then on, up until the 20th century, facial hair became the subject of numerous governmental orders and laws. It is difficult to trace those specifically targeting mustaches, as facial hair above the lip was often grouped with beard regulations, mostly due to a lack of precise terminology. The Romans, for instance, certainly knew about mustaches, but there was no Latin term for them.

In ancient Greece, however, where barbers were valued members of society as early as the 6th century BC, there were three distinct terms for the mustache, including 'mustax,' which the Italians later adopted during the Middle Ages as 'mustacchio.' This term was then borrowed by the French, likely during the 15th century, when King Charles VIII was conducting military campaigns in Southern Italy.

Despite the lack of a proper term, mustache grooming was important in France and across Western Europe long before the vocabulary to describe it was established. During the Middle Ages, barbering was a serious business. In addition to trimming hair, beards, and mustaches, barbers also performed medical procedures like bloodletting and tooth extraction. To regulate this intricate profession, the first-ever barber's guild was founded in France in 1076.

However, similar guilds quickly appeared in other countries. So what makes the mustache so distinctly French? Perhaps it's due to foreign monarchs like Henry VIII and Peter the Great, who imposed taxes on beards, making the mustache the fashionable choice. Since every French monarch from Francois I (born 1494) to Louis XIV (died 1715) sported a well-groomed mustache, the French became known for wearing it better than anyone else.

9. The Baguette

This French dietary essential may actually have foreign roots. While it is difficult to provide conclusive proof, there is enough evidence to question the claim that the baguette originated in France. Of the three leading theories regarding its creation, the two suggesting French origins appear flawed, while the third theory, which links the baguette to Austrian bakers, seems far more plausible.

One theory claims that the baguette was a Napoleonic invention. The story goes that the round bread, known as a 'boule,' was too bulky for soldiers to carry and weighed between 3 and 6 kilograms (6.6–13.2 lb), so Napoleon had the baguette created. However, the flaw in this theory lies in the bread's preservation. Anyone who has left a baguette out overnight knows it can't last for four days, which was the required ration period for soldiers in the Grand Army.

Another theory suggests that the baguette originated with the construction of the Parisian metro. Workers, who brought their heavy 'boules' for lunch, also carried knives to cut them. When disputes arose and fights broke out in the dark, underground tunnels, violence sometimes escalated. While this story could be true, it is too late to explain the origins of the baguette.

The baguette likely made its debut in Paris between the early 19th century, during Napoleon’s Grand Army, and the later stages of metro construction, which is why the third theory seems the most reasonable.

In 1839, an Austrian named August Zang opened a bakery in Paris called the Boulangerie Viennoise. He introduced a new steam-baking method using lightweight flour and beer as a leavening agent. Rather than making round loaves, he shaped the dough into elongated ovals. Zang’s bread likely evolved into the modern baguette in 1920 when a law was passed forbidding bakers from starting work before 4:00 AM. To ensure their breads were ready for breakfast, they made them thinner, allowing them to bake more quickly.

Although France’s president, Emmanuel Macron, may not have been entirely accurate when claiming that the baguette 'has been a part of humanity since its beginning,' it is hard to argue with his dedication to safeguarding this iconic, crunchy, and doughy delight by seeking UNESCO recognition as a world treasure.

8. The Croissant

If the baguette does indeed gain protection as a global treasure, its counterpart, the croissant, may follow suit. Like the baguette, the origins of the croissant are uncertain, but most accounts trace it back to Vienna and August Zang.

In 1683, Vienna faced an imminent attack by the Ottoman Empire. Early one morning, as Ottoman forces prepared to ambush the city, a group of bakers who were already up preparing bread overheard the enemy’s movements and raised the alarm, saving the city. As a reward, these bakers were allowed to create a unique pastry shaped like a crescent, the symbol of the Ottoman Empire.

These kipferl resembled a croissant in shape, but the dough used was entirely different. The pate feuillete, which gives a croissant its distinct texture, was not developed until the 17th century. Therefore, the 'crescent-shaped cakes' served by the Bishop of Paris at Catherine de Medici’s coronation in 1549 were definitely not croissants.

In 1838, August Zang brought not only the dough but also the technique to Paris. Back in Vienna, Zang was a young artillery officer with a promising military future, but an even greater aspiration. Some accounts say that during a visit to Paris, he was struck by the city's lack of quality pastries. Others suggest that during a trip to Vienna, a member of the French royal family commented on how much the French would appreciate Viennese breads. According to this tale, Zang resigned from his military post the next day, packed up, and set off for Paris, armed with recipes.

The French wasted no time in adopting the croissant and making it their own. By 1840, at least a dozen bakeries specializing in Viennoiserie were flourishing in Paris.

7. The Bicycle

The exact moment when the bicycle truly became what we recognize today is still debated. What is certain, however, is that in 1861, Pierre Michaud had the groundbreaking idea of adding pedals to a two-wheeled, human-powered vehicle that had already arrived in Paris. However, this vehicle was the German Draisine.

The Drasienne or velocipede, as it was called in France, was invented by Karl Drais von Sauerbonn, a German inventor and forestry official who seemingly preferred inventing over managing forest paths. The Draisine allowed him to move faster than walking, providing him with more time to experiment in his workshop.

Drais’s first human-powered wheeled invention was the laufmaschine (running machine), introduced in 1814. It was a bulky and unwieldy design, featuring four large wooden wheels and a basic steering system. By 1815, Drais had refined the concept, removing two of the wheels, replacing the other two with iron, and adding a rope brake for better control.

To be fair, Comte Mede de Sirvac, a French aristocrat, had already invented the celerifere, a two-wheeled contraption shaped like a horse, in 1791. However, it lacked steering, pedals, or brakes. Merriam-Webster clarifies that neither Mede de Sirvac’s nor Drais’s invention qualifies as a true bicycle, which it defines as: 'a vehicle with two wheels tandem, handlebars for steering, a saddle seat, and pedals by which it is propelled.'

Even if pedals are the key feature that makes the difference, the bicycle still isn’t French. Pedals first appeared on the dandy-horse, or hobby-horse as it was known in the UK, in 1839. A Scotsman, Kilpatrick Macmillan, invented a system of levers, cranks, and pedals to propel the vehicle forward.

6. The Cigarette

Much like its primary ingredient, tobacco, the cigarette is thoroughly American. Native to South America, where it has been growing for nearly 8,000 years, tobacco only made its way to Europe when Columbus brought back a small amount of seeds and leaves to Spain in the late 15th century.

Tobacco use didn’t become popular in Europe right away. It wasn’t until the mid-16th century that Jean Nicot, the French ambassador to Portugal, became convinced of the plant’s amazing medicinal properties. He sent some to Queen Catherine de Medici, along with instructions for its proper use: dried, ground, and inhaled as snuff. This method was believed to be a guaranteed remedy for headaches. Naturally, once the headache was gone, the relieved individual was on their way to developing an addiction to tobacco’s then-unknown ingredient, which was later named in honor of Mr. Nicot.

In Nicot’s time, tobacco use was restricted to snuff, pipe smoking, and chewing. The earliest known use of rolled tobacco leaves dates back to the second half of the first millennium in Guatemala. After 1492, explorer Rodrigo de Jerez attempted to bring rolled tobacco to Spain but was arrested. 'The smoke billowing from his mouth and nose so frightened his neighbors that he was imprisoned by the holy inquisitors for seven years.'

Meanwhile, in America, tobacco was thriving and even used as currency. The plant significantly impacted the colonial economy as well. In 1612, the first crops grown for commercial use were planted in Virginia. Later, American inventor James Bonsack developed the first rolling machine. The first prepackaged cigarette sellers? Americans as well. Allen and Ginter were also the first to export tobacco sticks to Europe. By 1883, they had their products in Austria, Belgium, France, Germany, and Switzerland, and had set up a factory in London.

Another American, James Duke, the first true king of cigarettes, had already secured a monopoly in the Western Hemisphere with his American Tobacco Company. In 1902, Duke struck a deal with Britain’s Imperial Tobacco. Once the deal was finalized, he remarked to the press: 'Is it not a grand thing in every way that England and America should join hands in a vast enterprise rather than be in competition? Come along with me and together we will conquer the rest of the world.'

5. French Fries

Believe it or not, French fries—or even 'freedom fries' if you prefer—are not from France. They actually originate in Belgium.

The potato, native to Chile and Peru, made its way to Europe through the Canary Islands. By the end of the 16th century, Spanish farmers were exporting them to Europe, but the French viewed them with suspicion, considering them fit only for animal feed. It wasn’t until 1772, when the esteemed army pharmacist Antoine Parmentier proclaimed the potato safe for human consumption, that it had any chance of eventually becoming the beloved fry in France.

In northern Belgium, people living along the Meuse River were accustomed to frying the small fish they caught in the river, slicing them into strips and frying them for snacks. However, in winter when the river froze and fish were scarce, villagers in towns like Namur and Dinant began slicing potatoes and frying them instead. By the late 17th century, Belgian fries had become a popular tradition.

Thomas Jefferson, who served as the US minister to France from 1784 to 1789, is credited with introducing the fry to America, though it wasn’t called the French fry. It only became known as 'French' after World War I when American soldiers stationed in Belgium brought the fry home with them. Since French is spoken in the Belgian regions along the Meuse River, they referred to the fry as French for the language, not the country. How do Belgians, who consume more fries than anyone else in the world, feel about the term? 'There’s no such thing as French fries.'

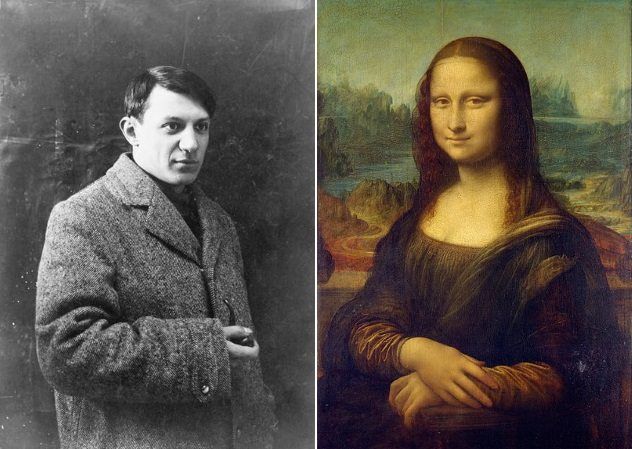

4. Picasso And The Mona Lisa

As much as the French are known for their love of the arts, they cannot claim ownership of some of the world’s most renowned artwork in their capital. The Picasso Museum in Paris, housing the world’s largest collection of Picasso’s work, is a key destination for art lovers. Yet, more visitors flock to the Louvre to admire the Mona Lisa more than any other piece in its collection. However, neither Pablo Picasso nor Mona Lisa have French origins.

Pablo Picasso, a Spaniard by birth, was born in 1881 and made Paris his home in 1904. He lived in France for the majority of his life until his death in 1973. However, despite his years in France, Picasso never held French citizenship. In fact, in 1940, at a time when France was on the brink of Nazi invasion and Franco’s dictatorship was in power in Spain, Picasso’s position as a foreigner was uneasy. Despite his communist leanings and outspoken atheism, Picasso applied for French citizenship in 1940 but was denied, as authorities considered him an anarchist with socialist tendencies.

Like Picasso, Leonardo da Vinci passed away as a foreign resident in France. However, da Vinci was already in his later years when he moved there in 1517, invited by King Francois I. The subject of his iconic portrait, Mona Lisa, was as Italian as da Vinci himself, hailing from Florence in 1503. But beyond this, little is known about the identity of the woman behind the painting.

There are three leading theories regarding the identity of the Mona Lisa, with the oldest dating back to 1550. One popular belief is that the model is Lisa del Giocondo, a theory widely accepted in France, where the painting is called La Joconde. Another theory, advanced by Sigmund Freud and others in the 19th century, suggests that the painting represents Leonardo’s mother, Caterina, embodying his deep emotional connection to her and his childhood. A third idea posits that the Mona Lisa is actually a self-portrait of the artist, symbolizing a personal riddle for viewers to solve.

In 2013, the Giocondo family tombs were excavated with the hope that DNA testing might finally provide an answer to the age-old mystery. Unfortunately, the exhumation did not bring us any closer to resolving the question.

3. The French Poodle

Although the poodle is often associated with France, its true origins are in Germany, where it is known as the Pudel, derived from pudelin, meaning “to splash in water.” In France, it is called the caniche, which blends the French words for “duck” (canard) and “dog” (chien). Renowned for its sharp intellect and remarkable ability to learn, it’s easy to see why the French embraced the poodle just as much as it embraced the French.

The poodle is also known for its fashionable appearance, but its role in France wasn’t just about looking good. As a purebred, the poodle was bred to be a hardworking companion. With its waterproof coat and exceptional swimming ability, the poodle was – and still is – the perfect partner for hunting ducks or other fowl that might land in water after being shot.

The standard poodle can be found in German art and literature as early as the 15th century. Germany officially recorded its Pudel in 1750. In France, dogs resembling the poodle are featured in statues (such as those at the 11th-century cathedral in Aix-en-Provence and the 13th-century cathedral in Amiens) and depicted in tapestries (like those at the 16th-century Cluny Abbey), but there was no formal acknowledgment of the caniche in France until 1885, when a male poodle named Milord was entered into the records.

Allez, venez, Milord!

2. The Accordion

The accordion was invented in Berlin by Friedrich Buschman in 1822 and was originally called the Handaoline. In 1829, Viennese musician Cyrillus Damian modified it by adding buttons to allow the left hand to play chords while the right hand played the melody. He renamed the instrument the accordion, derived from the French word for chord, accord. From Germany and Austria, the accordion spread to Italy. In the late 19th century, Italian immigrants brought the instrument to France, where it was embraced with such enthusiasm that accordion shops began to open in Paris, the first one in 1890.

The accordion swiftly became a key feature in cafes and cabarets, perfectly suited for musette music, which was played at the lively street balls in Paris during the early 20th century. The instrument also resonated with the French national spirit. Described as 'instantly recognizable,' its minor keys evoke an underlying sadness, while its lively melodies and performance styles reflect the resilience of the human spirit.

Few individuals did more to imbue the accordion with French identity than Edith Piaf. Born in Paris to a family of circus performers, Edith Gassion’s father was an acrobat, her mother a singer and dancer, and her grandmother trained fleas. By the time she was 14, Piaf was singing on the streets of the city, earning the nickname Mome Piaf, or 'little sparrow.' With an accordion in hand, she embraced this identity, rising from humble beginnings to international fame. She became the first French artist to conquer the American music scene and was France's foremost international star in the early 20th century. The melancholy and determination of her music is mirrored in the accordion she played.

1. The Guillotine

The guillotine may be synonymous with France, but its origins trace back to an outside influence.

The Halifax Gibbet from Yorkshire, England, is believed to have been in use since 1066, during the time of the Norman Conquest. The first mention of it appeared in 1280, and the first execution took place in 1286, with the victim being John of Dalton. Local law declared that 'If a felon be taken within the liberty of Halifax [...], whether hand-habend, back-berand, or confessand, to the value of thirteen pence half-penny, he shall [... ] be taken to the Gibbet and there have his head cut off from his body.'

Other European regions dealt with criminals in similar ways. In 1307, Murcod Ballagh lost his life to a guillotine-like device in Ireland. In Flanders and Germany, a beheading machine called the planke was used throughout the Middle Ages. During the Renaissance, the 'Scottish Maiden' was infamous, claiming over 120 victims. In 1702, Count Bozelli was among many to meet his end at the hands of the mannaia in Italy.

The guillotine was in constant use during the Reign of Terror following the French Revolution, to say the least. It also became widely utilized by the Nazis.

France's connection to the guillotine in the 1790s was strangely multifaceted. Miniature versions of the machine, measuring only about 0.6 meters (2 feet), were sold as toys, delighting children as they beheaded dolls, rodents, and anything else they could find. Surprisingly, smaller, functional replicas became a brief fashion among the wealthy, where they were used for slicing bread at the dinner table. The so-called 'Victim balls' also became a trend among aristocrats, though these were exclusive, and one had to have a relative who had been a victim of the guillotine to be invited.