The bubonic plague, known as the Black Death, swept across Europe between 1347 and 1351, eradicating one-third to two-thirds of the population. Despite the devastation, it brought unexpected improvements, such as increased literacy and enhanced labor rights. Discover 13 intriguing facts about the Black Death.

Humans have faced bubonic plague for thousands of years.

Archaeological studies have identified traces of bubonic plague in two Bronze Age skeletons from Russia, indicating the disease's ancient origins. The Justinianic Plague, which ravaged the Mediterranean and Near East in the 6th century CE, marks the first documented bubonic plague pandemic. (It is named after Byzantine emperor Justinian.) The 14th-century outbreaks, collectively called the Black Death, represent the second global plague pandemic.

Bubonic plague is a disease transmitted from animals to humans.

This highly contagious illness is triggered by the bacterium Yersinia pestis, which affects rats, small mammals, and humans. Fleas that feed on infected animals harbor the bacteria in their digestive systems. When the host rodents succumb to the disease, fleas seek new hosts, including humans and livestock, spreading the bacteria through their bites.

The name 'bubonic plague' originates from one of its most prominent symptoms.

A French statue from the early 16th century depicting Saint Roch, revered for his ability to heal plague victims. The statue shows him pointing to a bubo on his inner thigh. | The Cloisters Collection, 1925, Metropolitan Museum of Art // Public Domain

A French statue from the early 16th century depicting Saint Roch, revered for his ability to heal plague victims. The statue shows him pointing to a bubo on his inner thigh. | The Cloisters Collection, 1925, Metropolitan Museum of Art // Public DomainEarly signs of the plague include painful, swollen lymph nodes called 'buboes,' found in the neck, groin, and armpit, which lend the disease its name. As the condition worsens, patients suffer from headaches, vomiting, high fever, and discharge of blood and pus from the buboes. In medieval times, there was no effective treatment, and most victims died within a week. Modern medicine, however, can treat the plague with antibiotics.

The Black Death began in central Eurasia.

The outbreaks that sparked the Black Death emerged in central Eurasia. By the 1340s, the plague had spread through India, Syria, Persia, and Egypt, devastating populations before arriving in Europe in 1347.

The Black Death was employed as a biological weapon.

In 1347, during the siege of Kaffa, a Genoese trading port in present-day Crimea, Mongol leader Janibeg sought to expel Genoese merchants. However, his forces were severely weakened by the Black Death, making victory unlikely. In a desperate act of revenge, Janibeg's army used a trebuchet to hurl the corpses of plague-stricken soldiers into the city. The already beleaguered residents of Kaffa quickly succumbed to the disease.

The Black Death likely made its way into Europe via Messina, Sicily.

Rats, which thrive near humans, were common stowaways on merchant ships traveling between countries, often bringing disease with them. Medieval lore suggested that an abundance of dead rats signaled impending illness and disaster.

In 1347, Genoese vessels transported goods—and inadvertently, plague-infested rats—from Central Asia to Messina, Sicily. The plague rapidly swept across Europe, first devastating Italy before spreading to France, Spain, and Germany. By 1349, it reached England, and by 1350, Scandinavia. Historians have linked the plague's spread to merchant ships, as bustling ports like Kaffa provided ideal conditions for the pathogen to jump to new hosts and travel along global trade routes. Consequently, the highest fatalities were recorded in port cities and major urban centers like Venice and London.

The plague was not confined to the lower classes.

Although transmitted by fleas and rats, the Black Death was mistakenly labeled a 'peasant's disease,' thought to only affect those in unsanitary conditions. However, it impacted all levels of society, from the poorest to the wealthiest. Notable victims included Joan, the beloved daughter of England's King Edward III; Eleanor of Portugal, Queen of Aragon; King Alfonso XI of Castile; two archbishops of Canterbury, John de Stratford and Thomas Bradwardine; and the philosopher William of Ockham.

A religious sect attempted to stop the plague by engaging in self-flagellation.

Before the germ theory of disease was understood, the Black Death appeared as a divine punishment to many. Some believed public acts of penance could appease God and halt the plague's spread.

The flagellant movement, active in northern and central Europe since the 13th century, grew during the Black Death. Followers, including monks and devout individuals, marched through settlements, whipping themselves and urging others to repent. Their brutal practices, which often caused severe injuries and increased infection risks, led Pope Clement VI to condemn the movement.

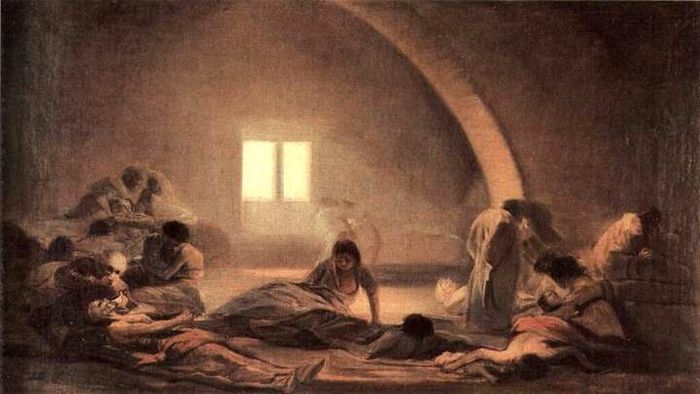

Quarantine measures were first implemented during the Black Death.

Although medieval people lacked knowledge of germ theory, they recognized the plague's contagious nature. Authorities enforced health measures to curb its spread, such as isolating symptomatic families in their homes or plague hospitals. Ships arriving in ports were required to wait 30 days before disembarking, a practice initiated in Venice in 1347. This method, later extended to 40 days, gave rise to the term 'quarantine,' derived from the Italian quaranta and Latin quadraginta, meaning 'forty.'

The Black Death occurred in multiple waves.

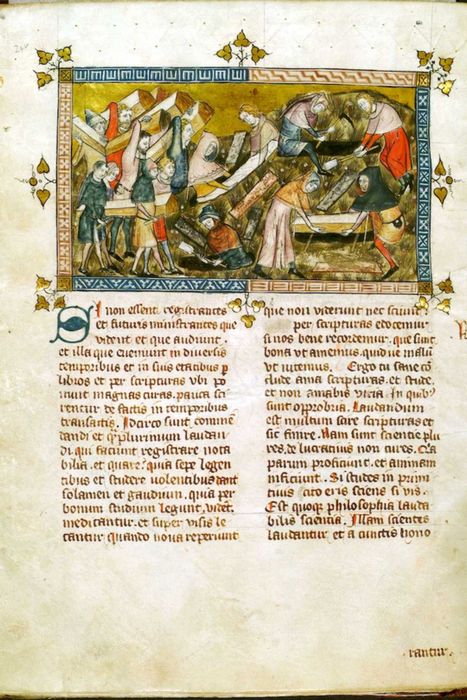

A 1349 miniature by Piérart dou Tielt in Gilles li Muisis’s ‘Antiquitates Flandriae’ portrays villagers transporting coffins for burial. | Royal Institute for Cultural Heritage // CC-BY KIK-IRPA, Brussels, X004173

A 1349 miniature by Piérart dou Tielt in Gilles li Muisis’s ‘Antiquitates Flandriae’ portrays villagers transporting coffins for burial. | Royal Institute for Cultural Heritage // CC-BY KIK-IRPA, Brussels, X004173The first wave of the Black Death struck Europe in 1347 and persisted until 1351, but the pandemic did not end there. It returned multiple times over the next five decades, with outbreaks in 1361–63, 1369–71, 1374–75, 1399, and 1400. These subsequent waves were brought to Europe by ships from Asia, spreading the disease along trade routes. Further epidemics occurred in the 17th century, including the devastating London outbreak of 1665–66, which claimed about a quarter of the city’s population.

The third global plague pandemic began in Yunnan, China, during the mid-19th century, rapidly spreading to Taiwan, Hong Kong, Japan, India, and beyond. It resulted in the deaths of 12 million people in India alone.

The cause of the plague remained unknown until the Victorian era.

By the 1890s, scientific progress enabled the identification of the bacteria causing bubonic plague. Researchers from various nations traveled to Asia in the late 19th century to study the disease. In 1894, Japanese bacteriologist Kitasato Shibasaburō identified the bacterium in India, closely followed by French-Swiss bacteriologist Alexandre Yersin. A dispute arose over who deserved credit for the discovery. Today, many historians regard both as co-discoverers, though the bacterium is named Yersinia pestis. (The genus Yersinia was named in Yersin’s honor in 1944.)

This breakthrough enabled Yersin’s successor, Paul-Louis Simond, to investigate a hypothesis linking plague outbreaks to dead rats. He noted, 'On live and recently deceased rats, fleas were more abundant than I had ever seen. There must be an intermediary between dead rats and humans—likely the flea.'

A straightforward experiment confirmed Simond’s theory, showing that fleas transmitted the plague from infected rats to healthy ones.

The term 'Black Death' for the 14th-century pandemic was not used until much later.

In England, the Black Death was commonly referred to as 'the pestilence,' while in much of Europe, it was called 'the plague' or 'the great dying.' Elizabeth Penrose, in her 1823 book A History of England, coined the term 'Black Death' for the 1347–51 outbreak—a name that captured its horror and endured.

Even earlier, 16th-century Danish and Swedish chronicles labeled a deadly plague in Iceland (1402–03) as the 'Black Death,' though the reason remains unclear. These chronicles were later translated into German and English, and the term was retroactively applied to the 14th-century European plague.

The Black Death had some positive outcomes.

Despite the devastating death toll, which wiped out an estimated 60 percent of Europe’s population, the Black Death spurred significant social changes. The resulting labor shortage led to higher wages and improved conditions for peasants. It also drove the development of labor-saving technologies, such as smaller, faster ships requiring fewer crew, enabling exploration and exploitation of Asia and the Americas.

Additionally, the loss of monks who copied manuscripts created a need for new methods of reproducing books, leading to the invention of the printing press and the widespread dissemination of ideas.