Khi ôn luyện phần IELTS Reading, người học có thể tham khảo nhiều phương pháp đọc khác nhau ví dụ như đọc phần câu hỏi trước để xác định key words (từ khóa quan trọng) rồi sau đó mới đi vào đọc bài sử dụng phương pháp skimming (đọc lướt) để định vị những key words đã xuất hiện ở phần câu hỏi. Sau khi định vị keywords xong, người học mới đọc hiểu kĩ hơn phần bài chứa key words để tìm ra đáp án. Đây là một phương pháp tiếp cận bài IELTS Reading khá phổ biến và được nhiều người áp dụng. Tuy nhiên, cách này không thật sự tối ưu khi người học muốn hiểu rõ nội dung bài đọc và trả lời câu hỏi một cách chính xác nhất để đạt 8.0 – 9.0 trong IELTS Reading.

Key takeaways

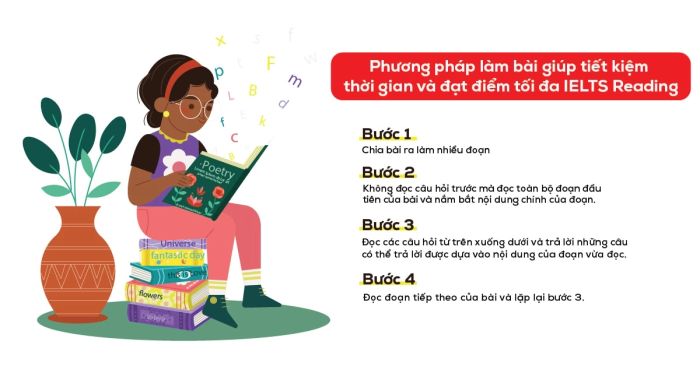

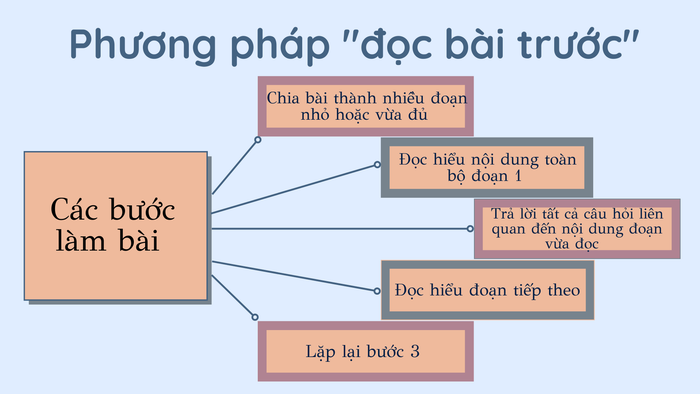

Các bước làm phương pháp “đọc bài trước” gồm: Chia bài ra làm nhiều đoạn nhỏ hoặc vừa đủ. Không đọc câu hỏi trước mà đọc toàn bộ đoạn đầu tiên của bài và nắm bắt nội dung chính của đoạn, đọc các câu hỏi từ trên xuống dưới và trả lời những câu có thể trả lời được dựa vào nội dung của đoạn vừa đọc. Sau khi giải quyết xong đoạn 1, đọc đoạn tiếp theo của bài và thực hiện các bước tương tự.

Cách thực hiện phương pháp “đọc trước bài”

Bước 2: Không đọc câu hỏi trước mà đọc toàn bộ đoạn đầu tiên của bài và nắm bắt nội dung chính của đoạn. (Khi đọc gạch chân từ khoá quan trọng để nắm nội dung đoạn một cách khái quát)

Bước 3: Đọc các câu hỏi từ trên xuống dưới và trả lời những câu có thể trả lời được dựa vào nội dung của đoạn vừa đọc. (Khi đọc lướt các câu hỏi cũng gạch chân từ khoá luôn để dễ ghi nhớ nội dung câu hỏi khi làm các đoạn tiếp theo)

Bước 4: Đọc đoạn tiếp theo của bài và lặp lại bước 3.

Hiệu quả của phương pháp “đọc trước bài”

Ví dụ về cách áp dụng phương pháp “đọc trước bài”

READING PASSAGE 1

You should spend about 20 minutes on Questions 1-13 which are based on Reading Passage 1 below.

Roman shipbuilding and navigation

Shipbuilding today is based on science and ships are built using computers and sophisticated tools. Shipbuilding in ancient Rome, however, was more of an art relying on estimation, inherited techniques and personal experience. The Romans were not traditionally sailors but mostly land-based people, who learned to build ships from the people that they conquered, namely the Greeks and the Egyptians.

There are a few surviving written documents that give descriptions and representations of ancient Roman ships, including the sails and rigging. Excavated vessels also provide some clues about ancient shipbuilding techniques. Studies of these have taught us that ancient Roman shipbuilders built the outer hull first, then proceeded with the frame and the rest of the ship. Planks used to build the outer hull were initially sewn together. Starting from the 6th century BCE, they were fixed using a method called mortise and tenon, whereby one plank locked into another without the need for stitching. Then in the first centuries of the current era, Mediterranean shipbuilders shifted to another shipbuilding method, still in use today, which consisted of building the frame first and then proceeding with the hull and the other components of the ship. This method was more systematic and dramatically shortened ship construction times. The ancient Romans built large merchant ships and warships whose size and technology were unequalled until the 16th century CE.

…….

Questions 1-5

Do the following statements agree with the information given in Reading Passage 1?

In boxes 1-5 on your answer sheet, write

TRUE if the statement agrees with the information

FALSE if the statement contradicts the information

NOT GIVEN if there is no information on this

1 The Romans’ shipbuilding skills were passed on to the Greeks and the Egyptians.

2 Skilled craftsmen were needed for the mortise and tenon method of fixing planks.

3 The later practice used by Mediterranean shipbuilders involved building the hull before the frame.

4 The Romans called the Mediterranean Sea Mare Nostrum because they dominated its use.

5 Most rowers on ships were people from the Roman army.

Questions 6-13

Complete the summary below.

Choose ONE WORD ONLY from the passage for each answer.

Write your answers in boxes 6-13 on your answer sheet.

Warships and merchant ships

Warships were designed so that they were 6 ………………… and moved quickly. They often remained afloat after battles and were able to sail close to land as they lacked any additional weight. A battering ram made of 7 ………………… was included in the design for attacking and damaging the timber and oars of enemy ships. Warships, such as the ‘trireme’, had rowers on three different 8 ………………… .

Unlike warships, merchant ships had a broad 9 ………………… that lay far below the surface of the sea. Merchant ships were steered through the water with the help of large rudders and a tiller bar. They had both square and 10 ………………… sails. On merchant ships and warships, 11 ………………… was used to ensure rowers moved their oars in and out of the water at the same time.

Quantities of agricultural goods such as 12 ………………… were transported by merchant ships to two main ports in Italy. The ships were pulled to the shore by 13 ………………… . When the weather was clear and they could see islands or land, sailors used landmarks that they knew to help them navigate their route.

Bước 1: Chia đoạn.

Bước 2: Đọc toàn bộ đoạn 1, highlight từ khoá quan trọng để nắm được nội dung chính của đoạn.

Shipbuilding today is based on science and ships are built using computers and sophisticated tools. Shipbuilding in ancient Rome, however, was more of an art relying on estimation, inherited techniques and personal experience. The Romans were not traditionally sailors but mostly land-based people, who learned to build ships from the people that they conquered, namely the Greeks and the Egyptians. (Q1)

=> Nội dung chính của đoạn : Đóng tàu thời Rome cổ là nghệ thuật dựa vào sự ước chừng, kĩ năng được thừa kế và kinh nghiệm cá nhân chứ không phụ thuộc vào thiết bị hiện đại như ngày nay. Người Roman vốn không phải thuỷ thủ, họ học đóng tàu từ người Hy Lạp và Ai Cập.

Bước 3: Trả lời tất cả các câu hỏi liên quan.

Trả lời được luôn Q1 với đáp án là F. Vì theo bài, người Roman học đóng tàu từ Người Hy Lạp và người Ai cập chứ không phải kĩ năng đóng tàu được truyền lại (were passed on to) cho người Hy Lạp và Ai Cập

* Lưu ý: Rà soát các câu hỏi còn lại, nếu không còn câu này có liên quan đến nội dung đoạn 1 nữa thì chuyển sang đoạn tiếp theo và thực hiện các bước tương tự. Có thể thấy nhanh Q2 nhắc đến “mortise và tenon method”, Q3 nhắc đến “Mediterranean shipbuilders”, Q4 nhắc đến “Sea Mare Nostrum” và Q5 nhắc đến “Roman army” đều không liên quan đến nội dung của đoạn 1. Lướt nhanh Q6-13 thì rõ ràng yêu cầu hoàn thành một passage nói về warships và merchant ships. Ta không thấy hai từ khoá này không xuất hiện trong đoạn 1. Đến đây, về cơ bản, người đọc đã nắm được nội dung của toàn bộ câu hỏi và giải quyết xong đoạn 1, không cần phải vướng bận hay quay lại đọc đoạn 1 nữa.

Bước 4: Làm đoạn 2, lặp lại các bước 2 và 3

There are a few surviving written documents that give descriptions and representations of ancient Roman ships, including the sails and rigging. Excavated vessels also provide some clues about ancient shipbuilding techniques. Studies of these have taught us that ancient Roman shipbuilders built the outer hull first, then proceeded with the frame and the rest of the ship. Planks used to build the outer hull were initially sewn together. Starting from the 6th century BCE, they were fixed using a method called mortise and tenon, whereby one plank locked into another without the need for stitching. (Q2) Then in the first centuries of the current era, Mediterranean shipbuilders shifted to another shipbuilding method, still in use today, which consisted of building the frame first and then proceeding with the hull and the other components of the ship. (Q3) This method was more systematic and dramatically shortened ship construction times. The ancient Romans built large merchant ships and warships whose size and technology were unequalled until the 16th century CE.

=> Nội dung chính: Thứ tự các bước đóng tàu của người Roman cổ và sự phát triển của quy trình đóng tàu qua thời gian. Người Roman cổ đóng thân tàu (outer hull) trước rồi đến khung (frame) và các bộ phận còn lại. Các tấm gỗ dùng để đóng thân tàu ban đầu đều gắn lại với nhau. Sau này dùng phương pháp “mortise and tenon” thì không cần phải khâu gắn các tấm gỗ này nữa. Thợ đóng tàu vùng Địa Trung Hải (Mediterranean shipbuilders) sau này lại đóng khung tàu (frame) trước rồi mới đến thân (hull) và các bộ phận khác. Cách đóng tàu này vẫn còn được áp dụng đến ngày nay bởi nó giúp rút ngắn thời gian đóng tàu.

Trả lời được Q2 là NG vì thông tin “skilled craftsmen were needed” không xuất hiện ở đoạn nói về phương pháp “mortise and tenon”

Trả lời được Q3 là F vì theo bài thì thợ đóng tàu vùng Địa Trung Hải đóng khung trước (“frame first”) chứ không phải “hull before frame” (đóng thân trước khung)

*Lưu ý : Những câu F có chưa thông tin sai mà người đọc có thể dựa vào nội dung bài để sửa lại cho đúng. Ví dụ ở Q3, phải sửa “hull before frame” thành “frame before hull” thì mới đúng theo nội dung bài đọc. Những câu NG là câu có thông tin không xuất hiên, không được nhắc đến trong bài (ví dụ xem Q2)

Practice

Nutmeg — a valuable spice

The nutmeg tree, Myristicafragrans, is a large evergreen tree native to Southeast Asia. Until the late 18th century, it only grew in one place in the world: a small group of islands in the Banda Sea, part of the Moluccas — or Spice Islands — in northeastern Indonesia. The tree is thickly branched with dense foliage of tough, dark green oval leaves, and produces small, yellow, bell-shaped flowers and pale yellow pear-shaped fruits. The fruit is encased in a fleshy husk. When the fruit is ripe, this husk splits into two halves along a ridge running the length of the fruit. Inside is a purple-brown shiny seed, 2—3 cm long by about 2cm across, surrounded by a lacy red or crimson covering called an 'aril'. These are the sources of the two spices nutmeg and mace, the former being produced from the dried seed and the latter from the aril.

Nutmeg was a highly prized and costly ingredient in European cuisine in the Middle Ages, and was used as a flavouring, medicinal, and preservative agent. Throughout this period, the Arabs were the exclusive importers of the spice to Europe. They sold nutmeg for high prices to merchants based in Venice, but they never revealed the exact location of the source of this extremely valuable commodity. The Arab-Venetian dominance of the trade finally ended in 1512, when the Portuguese reached the Banda Islands and began exploiting its precious resources.

Always in danger of competition from neighbouring Spain, the Portuguese began subcontracting their spice distribution to Dutch traders. Profits began to flow into the Netherlands, and the Dutch commercial fleet swiftly grew into one of the largest in the world. The Dutch quietly gained control of most of the shipping and trading of spices in Northern Europe. Then, in 1580, Portugal fell under Spanish rule, and by the end of the 16th century the Dutch found themselves locked out of the market. As prices for pepper, nutmeg, and other spices soared across Europe, they decided to fight back.

In 1602, Dutch merchants founded the VOC, a trading corporation better known as the Dutch East India Company. By 1617, the VOC was the richest commercial operation in the world. The company had 50,000 employees worldwide, with a private army of 30,000 men and a fleet of 200 ships. At the same time, thousands of people across Europe were dying of the plague, a highly contagious and deadly disease. Doctors were desperate for a way to stop the spread of this disease, and they decided nutmeg held the cure. Everybody wanted nutmeg, and many were willing to spare no expense to have it. Nutmeg bought for a few pennies in Indonesia could be sold for 68,000 times its original cost on the streets of London. The only problem was the short supply. And that's where the Dutch found their opportunity.

The Banda Islands were ruled by local sultans who insisted on maintaining a neutral trading policy towards foreign powers. This allowed them to avoid the presence of Portuguese or Spanish troops on their soil, but it also left them unprotected from other invaders. In 1621, the Dutch arrived and took over. Once securely in control of the Bandas, the Dutch went to work protecting their new investment. They concentrated all nutmeg production into a few easily guarded areas, uprooting and destroying any trees outside the plantation zones. Anyone caught growing a nutmeg seedling or carrying seeds without the proper authority was severely punished. In addition, all exported nutmeg was covered with lime to make sure there was no chance a fertile seed which could be grown elsewhere would leave the islands. There was only one obstacle to Dutch domination. One of the Banda Islands, a sliver of land called Run, only 3 km long by less than 1 km wide, was under the control of the British. After decades of fighting for control of this tiny the Dutch and British arrived at a compromise settlement, the Treaty of Breda, in 1667. Intent on securing their hold over every nutmeg-producing island, the Dutch offered a trade: if the British would give them the island of Run, they would in turn give Britain a distant and much less valuable island in North America. The British agreed. That other island was Manhattan, which is how New Amsterdam became New York. The Dutch now had a monopoly over the nutmeg trade which would last for another century.

Then, in 1770, a Frenchman named Pierre Poivre successfully smuggled nutmeg plants to safety in Mauritius, an island off the coast of Africa. Some of these were later exported to the Caribbean where they thrived, especially on the island of Grenada. Next, in 1778, a volcanic eruption in the Banda region caused a tsunami that wiped out half the nutmeg groves. Finally, in 1809, the British returned to Indonesia and seized the Banda Islands by force. They returned the islands to the Dutch in 1817, but not before transplanting hundreds of nutmeg seedlings to plantations in several locations across southern Asia. The Dutch nutmeg monopoly was over.

Today, nutmeg is grown in Indonesia, the Caribbean, India, Malaysia, Papua New Guinea and Sri Lanka, and world nutmeg production is estimated to average between 10,000 and 12,000 tonnes per year.

Questions 1-4

Complete the notes below.

Choose ONE WORD ONLY from the passage for each answer.

Write your answers in boxes 1—4 on your answer sheet.

The nutmeg tree and fruit

|

Questions 5—7

Do the following statements agree with the information given in Reading Passage 1?

In boxes 5—7 on your answer sheet, write

TRUE if the statement agrees with the information

FALSE if the statement contradicts the information

NOT GIVEN if there is no information on this

5. In the Middle Ages, most Europeans knew where nutmeg was grown.

6. The VOC was the world's first major trading company.

7. Following the Treaty of Breda, the Dutch had control of all the islands where nutmeg grew.

Questions 8—13

Complete the table below.

Choose ONE WORD ONLY from the passage for each answer.

Write your responses in boxes 8—13 on your answer sheet.

Middle Ages | Nutmeg was brought to Europe by the 8…………………………. |

16th century | European nations took control of the nutmeg trade |

17th century | Demand for nutmeg grew, as it was believed to be effective against the disease known as the 9…………………………. The Dutch -- took control of the Banda Islands — restricted nutmeg production to a few areas — put 10…………………………. on nutmeg to avoid it being cultivated outside the islands — finally obtained the island of 11…………………………. from the British |

Late 18th century | 1770 — nutmeg plants were secretly taken to 12 …………………………. 1778 — half the Banda Islands' nutmeg plantations were destroyed by a 13 |

Key

oval

husk

seed

mace

FALSE

NOT GIVEN

TRUE

Arabs

plague

lime

Run

Mauritius

tsunami