U.S. Army Rangers execute a water infiltration mission using a Zodiac inflatable boat.

Image provided by U.S. Army

U.S. Army Rangers execute a water infiltration mission using a Zodiac inflatable boat.

Image provided by U.S. ArmyThe U.S. Army Rangers stand out as a unique unit within the U.S. military's special operations forces. While their history dates back to the colonial period, they only became a permanent fixture in the 1970s. Initially, they were assembled for specific missions and disbanded afterward.

Renowned for their stealth, Rangers excel at remaining unseen in combat. If you encounter a Ranger during a battle, chances are they've already identified you. You won't know how long they've been watching, and by the time you notice them, it's often too late.

The Rangers were officially activated in the 20th century during the early stages of U.S. involvement in World War II. Inspired by the British Commandos, American leaders sought to establish a specialized combat unit. Major William Darby brought this vision to life in just over three weeks, forming the First Ranger Battalion at Sunnyland Camp in Carrickfergus, Ireland. He selected 600 individuals from thousands of volunteers [source: SpecialOperations.com].

The British commando forces played a key role in shaping the Rangers. They developed an exceptionally rigorous training program, so demanding that one-sixth of the participants dropped out -- unable to meet the requirements -- while one trainee lost his life and five others sustained injuries.

Initially, these pioneering Army Rangers operated alongside the British commandos who trained them. Later, they independently executed small-scale assaults in Algeria, Tunisia, Sicily, Italy, and France, penetrating enemy defenses and paving the way for larger military units to follow.

However, these operations resulted in significant Ranger casualties. To address this, the Rangers began replenishing their ranks by integrating skilled and resilient soldiers from other units. These elite groups, battle-hardened and prepared for Ranger duties, often overcame incredible odds. One such unit was the 5307th Composite Unit, tasked with reclaiming the Burma Road from Japanese forces during World War II. This regiment trekked 1,100 miles from their training base in India through the Burmese jungle, triumphing in numerous engagements with Japanese troops [source: SpecialOperations.com].

During the Vietnam War, long-range patrols -- small, stealthy units capable of operating undetected behind enemy lines for extended periods -- carried out raids and reconnaissance missions. These patrols were later integrated into the Ranger units deployed in Vietnam. Due to the urgency of wartime needs, Ranger candidates were trained through real missions, known as the "in-country Ranger school" [source: SpecialOperations.com]. Only after demonstrating their worth and skills were recruits officially inducted into the Rangers.

What does it take to become a U.S. Army Ranger? In this article, we explore the origins and roles of the Rangers. In the following section, we delve into the rich history of the Army Rangers.

Army Rangers History

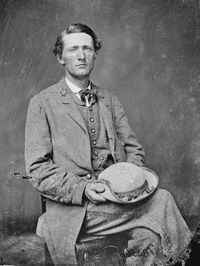

Confederate Colonel John Mosby is celebrated as the most effective Ranger commander during the Civil War.

Image provided by Library of Congress

Confederate Colonel John Mosby is celebrated as the most effective Ranger commander during the Civil War.

Image provided by Library of CongressThe Army Rangers were shaped by the American wilderness and its indigenous inhabitants. The rugged landscapes and dense forests of the New World favored the ambush and raid strategies used by Native Americans, contrasting with the open-field battles typical of European warfare. To compete, European soldiers had to embrace similar guerrilla tactics.

In 1670, Captain Benjamin Church formed the first Ranger-like unit in American history. His group hunted down "King Philip," the English name for Wampanoag chief Metacomet. Church's men spent extended periods "ranging"—moving stealthily to locate the enemy. This practice coined the term "ranger." They turned Native American tactics against them, launching swift, unexpected attacks based on intelligence gathered during their missions [source: U.S. Army Ranger Association].

Major Robert Rogers is recognized for founding the first official Ranger company. During the French and Indian War, he organized this group in 1756 to aid the British. Composed of skilled deer hunters, the unit excelled in moving silently through forests, tracking, and accurately using the era's unreliable firearms [source: U.S. Army Ranger Association].

Rogers built on the expertise of his men, tailoring their skills for warfare and formulating 28 tactical guidelines. These rules covered ambushes, marching strategies, prisoner handling, retreats, and reconnaissance. Known as Rogers' Standing Orders for Rangers, 19 of these principles are still applied by the 75th Ranger Regiment today [source: SOC].

The most renowned Ranger unit of the Civil War was likely Colonel John Mosby's Confederate brigade. Mosby's troops distributed spoils from Union camp raids among locals, but it was their surprise attacks and guerrilla tactics that defined the Rangers. Mosby excelled at launching unpredictable strikes, consistently outmaneuvering the Union forces.

While the Rangers were absent in the Spanish-American War and World War I, they were reactivated during World War II. They fought in North Africa, Europe, and South Asia, laying the groundwork for today's modern Ranger Regiment. Before delving into their modern role, let's explore Rogers' Standing Orders for Rangers, the foundational principles of ranging.

Army Rangers Standing Orders

An engraved depiction of Robert Rogers

Image provided by Library of Congress

An engraved depiction of Robert Rogers

Image provided by Library of CongressRobert Rogers' directives are practical and straightforward. At the time of their creation, no one had compiled such a comprehensive set of tactical guidelines. Remarkably, these orders have endured over time, with many of their principles still guiding Rangers today.

Rogers instructed his men as follows:

- Forget nothing.

- Keep your musket spotless, your hatchet sharpened, and carry 60 rounds of ammunition. Be prepared to move at a moment's notice.

- Move stealthily on the march, as if stalking a deer. Spot the enemy before they spot you.

- Always report truthfully. The army relies on accurate intelligence. While you can embellish stories for outsiders, never lie to a fellow Ranger or officer.

- Avoid unnecessary risks.

- March in single file, spacing yourselves so a single shot cannot hit two men.

- In swamps or soft terrain, spread out to obscure your tracks.

- Keep moving until nightfall to minimize the enemy's chances of attacking.

- While camping, half the group remains on watch while the other half rests.

- Separate prisoners immediately to prevent them from coordinating false stories.

- Never return by the same route. Vary your path to avoid ambushes.

- Whether in large or small groups, maintain scouts 20 yards ahead, on each flank, and behind to prevent surprise attacks.

- Each night, designate a rallying point in case of encirclement by a stronger force.

- Post sentries before eating.

- Never sleep past dawn, as it's the preferred time for French and Indian attacks.

- Avoid crossing rivers at common fords.

- If pursued, circle back to ambush your pursuers.

- When the enemy approaches, kneel, lie down, or take cover behind trees.

- Wait until the enemy is nearly within reach, then strike and finish them with your hatchet.

[source: U.S. Special Operations Command]

To demonstrate the effectiveness of these orders, Rogers once led 200 Rangers on a 400-mile journey over 60 days, culminating in a successful raid on an enemy encampment [source: U.S. Army Ranger Association].

These battle-tested strategies form the cornerstone of modern-day Rangers. In the following section, we'll examine the organization of the current 75th Ranger Regiment.

Army Rangers 75th Ranger Regiment Structure

Ranger companies are bolstered by three sniper teams, one of which is equipped with .50-caliber weapons like the one shown here.

Image provided by U.S. Army

Ranger companies are bolstered by three sniper teams, one of which is equipped with .50-caliber weapons like the one shown here.

Image provided by U.S. ArmyThe 75th Ranger Regiment was established at the start of the Korean War, with its headquarters at Fort Benning, Georgia. Initially, volunteers were selected solely from the 82nd Airborne Division. This practice persists today, as all Ranger candidates must complete airborne training before earning their Ranger designation.

To qualify as a Ranger, a soldier must demonstrate physical fitness and complete rigorous calisthenics and endurance challenges, such as extended runs and hikes. Upon acceptance into Ranger school, training commences, divided into three progressive phases: crawl, walk, and run.

- Crawl training forms the foundation of Ranger instruction. It covers hand-to-hand combat, pugilism -- fighting with fists or sticks -- and assessments of comfort in water-based scenarios.

- Walk training represents the intermediate stage. It focuses on rappelling, knot-tying, and the planning and execution of ambushes and airborne missions.

- Run training is the most advanced phase, culminating in graduation from Ranger school. Recruits master water infiltration, urban assault, and troop extraction -- evacuating soldiers from hostile zones, often using a helicopter. Additionally, they acquire expertise in sabotage, navigation, explosives, and reconnaissance.

[source: U.S. Army]

Officers who finish the training program advance to the Ranger Orientation Program, a set of courses designed to familiarize them with Ranger policies and procedures [source: U.S. Army]. This program mirrors the Ranger Indoctrination Program offered to enlisted personnel.

Although the 75th Ranger Regiment was activated at the start of the Korean War, it was deactivated once hostilities ended. It followed a similar pattern during the Vietnam War. The establishment of a permanent Ranger unit came about when a commander recognized the importance of maintaining a ready Ranger force. In 1974, General Creighton Abrams, Chief of Staff for the Army, ordered the creation of the 1st Ranger Battalion of the 75th Ranger Regiment [source: SpecialOperations.com]. This marked the first peacetime activation of a Ranger force, leading to the current structure of the 75th:

- 1st Battalion - based at Hunter Airfield, Ga.

- 2nd Battalion - established in 1974 and located at Ft. Lewis, Wash.

- 3rd Battalion - formed in 1984 as part of a broader Ranger expansion and stationed at Ft. Benning, Ga.

[source: SpecialOperations.com]

Each battalion includes a Headquarters and Headquarters Command (HHC) and three rifle companies. With a maximum of 580 Rangers, each rifle company comprises 152 riflemen, while the rest serve in fire support and headquarters roles.

Fire support is crucial to Ranger missions. The Ranger weapon company delivers moderate firepower, featuring heavy machine guns, Stinger missiles, a mortar unit, and the Carl Gustav Anti-Armor Weapon. Exclusive to Rangers, the Gustav is a shoulder-fired launcher that can fire armor-piercing and smoke rounds. Additionally, fire support includes two two-man sniper teams and a third team equipped with .50-caliber sniper rifles. Despite this arsenal, Rangers remain a light-infantry force. For heavier firepower, they depend on the company they are supporting or operating alongside.

The Ranger Regiment can deploy globally within 18 hours, thanks to the Ranger Ready Force (RRF). This 13-week rotation among the three battalions ensures readiness. During their RRF rotation, battalions refrain from off-base exercises or training. Soldiers receive necessary vaccinations, weapons are inspected and replaced if needed, and all mission supplies are pre-packed and crated.

In the next section, we'll explore the types of missions Rangers undertake once deployed.

Army Rangers Duties

Rangers excel at executing swift, direct-action raids with small teams.

Image provided by U.S. Army

Rangers excel at executing swift, direct-action raids with small teams.

Image provided by U.S. ArmyThe core of Ranger operations lies in their ability to act as swift "shock troops"—specialized units capable of executing surprise attacks. However, their methods of reaching the target zone, their actions upon arrival, and the command structure directing them vary significantly depending on the mission.

As Airborne graduates, Rangers frequently parachute into their designated insertion points. They are also skilled in alternative insertion techniques—methods for swiftly and stealthily infiltrating enemy territory—such as using small boats in swamps or descending fast lines (rapid rope descents) from helicopters. Once on the ground, their missions can take various forms. A classic example is the seizure of an airfield during a strike operation.

Rangers are highly adaptable, capable of transitioning from special operations to conventional warfare once the initial objective is achieved. For instance, after parachuting into an airfield, neutralizing threats, and securing the area, they can signal mission completion. When conventional forces arrive, Rangers can integrate with them, continuing as part of a larger combat unit.

These missions, known as direct-action operations, often involve intense gunfire and can become quite chaotic. Rangers are also adept at reconnaissance, or recon, a skill rooted in their history as Colonial scouts and refined during Vietnam's long-range patrols. While all Rangers are trained in recon, a specialized unit, the Regimental Reconnaissance Detachment (RRD), focuses exclusively on advanced scouting and reconnaissance.

Established in 1984 during the Ranger expansion, the RRD comprises three four-man teams of highly skilled scouts. These teams can operate silently behind enemy lines for up to five days with minimal movement [source: SpecWarNet]. With only 12 such soldiers in the entire 75th Regiment, each team is assigned to one of the three battalions. RRD Rangers verify intelligence, deploy surveillance equipment, monitor enemy movements, and call in strikes. While they may occasionally conduct direct-action missions, their primary goal is to remain undetected.

Rescue missions are a perfect fit for Rangers, often blending direct action with reconnaissance. They must first verify intelligence about the location of missing troops or prisoners of war (POWs), frequently engaging enemy forces to secure their target. Rangers excel in these missions due to their swift infiltration and extraction skills, endurance for long-distance travel, stealth capabilities, and light-infantry expertise. This allows them to access areas that are otherwise inaccessible.

One of the most famous Ranger rescue missions was led by Colonel Henry Mucci. In the following section, we'll explore Mucci's Rangers and other significant Ranger operations.

Army Rangers Notable Operations

A Ranger mans a roadblock during Operation Just Cause in Panama.

Image provided by U.S. Army

A Ranger mans a roadblock during Operation Just Cause in Panama.

Image provided by U.S. ArmyThe success of the Allied invasion of Normandy during World War II is largely attributed to the efforts of the Rangers. The operation was exceptionally deadly, with Allied forces suffering up to 10,000 casualties in just a few days. German defenses were strategically positioned, with machine gunners stationed on cliffs offering a clear view of the beach below.

The Rangers' motto originated during this critical moment. Realizing that no other unit could breach the German defenses, Brigadier General Norman Cota urged the 5th Battalion on the beach, "Rangers, lead the way!" The Rangers responded by breaking through the enemy's beachhead, scaling the cliffs to neutralize German machine-gun positions, and creating a path for the main forces to advance [source: SpecialOperations.com].

World War II also saw some of the Rangers' heaviest casualties. In Cisterna, Italy, the Rangers penetrated Axis lines, only to have the front collapse behind them, cutting off Allied reinforcements and leaving the Rangers stranded. Nearly three battalions were lost, prompting the integration of the 5307th composite unit, known as Merrill's Marauders—the force that reclaimed Burma Road from the Japanese—to rebuild their numbers [source: SpecialOperations.com].

During World War II in the Philippines, Colonel Mucci and his Rangers, alongside Filipino guerrillas, launched a daring raid on a Japanese prison camp holding Allied POWs. The prisoners were slated for execution once the camp was no longer needed. Mucci's team liberated 500 POWs, killed 200 Japanese soldiers, and escaped into the jungle, carrying some prisoners on their backs for up to two days [source: SpecialOperations.com].

Rangers have also played key roles in peacetime operations, such as Operation Urgent Fury in Grenada in 1983. After an airborne insertion, they secured a medical facility where Americans were trapped during a violent uprising. The Rangers rescued the Americans and helped stabilize the situation, leading to the formation of the 3rd Battalion the following year [source: GlobalSecurity.org].

The Rangers were also instrumental in Panama in 1989. All three battalions participated in the invasion to oust dictator General Manuel Noriega. As part of Operation Just Cause, they seized airfields and airports, engaging the Panamanian Defense Force in intense combat [source: GlobalSecurity.org].

The Rangers have also faced setbacks. Operation Eagle Claw—the 1980 mission to rescue 66 American hostages from the U.S. embassy in Tehran, Iran—ended in failure, resulting in the deaths of eight team members. Similarly, during Operation Restore Hope in Somalia, the special operations force, including Rangers, lost 18 soldiers in just 18 hours [source: SpecialOperations.com]. This intense battle is famously depicted in the book and film "Blackhawk Down."

Despite their small numbers, the Rangers have consistently made a significant impact. For instance, during World War II, only 3,000 of the 15 million Allied troops were Army Rangers [source: World War II Army Rangers].

For more details on the Rangers and related topics, explore the links provided on the next page.