Wherever you dine, hot sauce is almost always within reach. This fiery condiment enhances dishes worldwide, from kimchi to buffalo wings, yet its presence outside Central and South America is relatively recent. It wasn’t until the 15th century that chili peppers began their global conquest. Curious about the origins of Tabasco sauce or the true significance of Scoville Heat Units? Dive in to find out.

Hot Sauce’s Medicinal Roots

Today, hot sauce is a globally beloved condiment, but its roots trace back to the Americas. While the exact origin of the first chili pepper-based sauce remains a mystery, with contenders from Bolivia to Mexico, it’s clear that Central and South Americans have been crafting hot sauces for thousands of years—and not just for flavor.

For the Aztec and Maya civilizations, chili peppers held significant medicinal value. | Jenny Dettrick/Moment/Getty Images

For the Aztec and Maya civilizations, chili peppers held significant medicinal value. | Jenny Dettrick/Moment/Getty ImagesThe Aztecs and Maya revered chili peppers for their healing qualities, using them to treat sore throats, stomach aches, asthma, and colds. While modern science confirms that hot sauce isn’t a universal remedy, it does possess pain-relieving properties. Chili peppers are rich in capsaicinoids, particularly capsaicin, which creates a fiery sensation upon contact with sensitive tissues.

After the initial burning sensation, capsaicin triggers a flood of endorphins in the brain, leading to an anti-inflammatory response across the body. This mechanism has inspired medical experts to explore capsaicin as a natural painkiller, much like the ancient Aztecs, who used chili pepper extracts to soothe toothaches.

For thousands of years, humans have cherished chili peppers for their intense heat, a trait that evolved to deter animals. This raises an intriguing question: Why would a fruit develop traits to avoid being consumed, when spreading seeds often relies on being eaten?

Birds may have played a crucial role in spreading pepper seeds. | Juana Mari Moya/Moment/Getty Images

Birds may have played a crucial role in spreading pepper seeds. | Juana Mari Moya/Moment/Getty ImagesThe difference lies in the type of animal consuming the pepper. Small mammals often crush the seeds with their teeth, hindering the plant’s reproduction. Birds, however, lack teeth and can eat peppers while leaving the seeds unharmed, aiding in their dispersal. Additionally, birds’ taste receptors don’t react to capsaicin like mammals’, making peppers less off-putting to them. This evolutionary trait likely discouraged mammals while attracting birds—and eventually, humans.

Hot sauce lets us infuse the flavor of peppers into nearly any dish. Ancient Mesoamericans not only used it medicinally but also paired it with corn tortillas. Their early versions of hot sauce were likely simple blends of ground peppers, water, and herbs. Without access to ingredients like onions or garlic, they instead developed new pepper varieties. By the time Spanish Conquistadors arrived, peppers such as anchos, jalapeños, and cayenne were already staples in the local cuisine.

The Global Spread of Peppers and Hot Sauce

Peppers were among the most thrilling finds that explorers brought back to Europe from the Americas. They were tasty, economical to cultivate, and thrived in diverse climates. The Spaniards adopted the Aztec Nahuatl term chilli, while the name pepper was inspired by its resemblance to black pepper, Europe’s dominant spice before the Columbian Exchange. Prior to this, hot peppers were exclusive to the Americas.

Chilies revolutionized the culinary traditions of many regions they touched. Introduced to Asia by Portuguese traders in the early 16th century, they gained immediate popularity. Due to their low cost and delightful flavor, chili peppers soon overshadowed black pepper as the go-to spice across much of Asia.

Sambal sauce served on spoons. | R¸ther, Manuela/FoodCollection/Getty Images

Sambal sauce served on spoons. | R¸ther, Manuela/FoodCollection/Getty ImagesSimilar to ancient Mesoamerican practices, Asian chefs began blending peppers with liquids and seasonings to create versatile sauces. These condiments had a more pungent profile compared to the Aztec tortilla dips. Thailand introduced nam phrik, a blend of peppers with fish sauce or fermented shrimp paste. Indonesia contributed hundreds of variations of sambal, a crushed chili condiment. In Korea, the fermented pepper paste gochujang became so essential that it inspired a spiciness measurement known as the Gochujang Hot-taste Unit.

Hot peppers reached Africa through Portuguese traders, and many African cultures quickly adopted these affordable flavor enhancers. One of the most popular hot sauces in southern Africa is piri piri, which translates to “pepper pepper” in Ronga. This sauce is crafted from African Birdseye chilies—a locally cultivated pepper variety—alongside ingredients like lemon, vinegar, garlic, oil, and herbs. It enjoys widespread popularity in countries such as Angola, Namibia, and Mozambique.

European colonization and global trade also reshaped hot sauce in its native region. Today, the Americas relish spicy condiments like Chilean pebre, a blend of tomatoes, onions, and chilies, and garlic-infused Mexican hot sauces from brands like Cholula and Tapatio.

Instacart data reveals that Cholula is America’s favorite hot sauce, though it isn’t the oldest. In 1807, a Massachusetts newspaper advertised a pepper sauce, which some claim was the first commercial hot sauce in the U.S.

However, this claim is debated. Food historian Charles Perry argues that the product was likely not a hot sauce but one of many “pepper-flavored vinegar ketchups” used to enhance food during that era. Perry notes that the preparation methods of the time would have extracted little to no capsaicin, and New Englanders of that period generally avoided spicy foods.

Perry suggests that wealthy British travelers in the early 19th century might have infused hot peppers into sherry bottles, possibly as an anti-scurvy remedy. Over time, this practice evolved into a way to add flavor to bland ship meals, gradually cultivating a preference for spicy condiments.

The Rise of Tabasco

Regardless of its origins, by the late 1800s, several authentic American hot sauce brands emerged, including one that remains iconic today. Tabasco company founder Edmund McIlhenny began producing a fermented, vinegar-based pepper sauce in the late 1860s. He named the sauce Tabasco after the chili variety used, which itself was named after its Mexican region of origin.

Tabasco hot sauce on a supermarket shelf. | SOPA Images/GettyImages

Tabasco hot sauce on a supermarket shelf. | SOPA Images/GettyImagesTo maximize its reach, McIlhenny distributed the sauce in bulk to restaurants and hotels rather than directly to consumers. Its widespread presence in the hospitality industry made it a household name, and it quickly dominated the hot sauce market. Though founded in Louisiana, Tabasco had expanded across the U.S. and Europe by the 1870s.

The Tabasco company credits McIlhenny with inventing Tabasco sauce, but its origins remain contested. Two decades before McIlhenny’s first batch, Colonel Maunsel White created a similar sauce on his Louisiana plantation. He cultivated Tabasco chili peppers and preserved them by boiling with vinegar. In 1850, the New Orleans Daily Delta praised his sauce, stating it “captures the essence of the pepper in its most potent form” and that “a mere drop can flavor an entire dish.”

Some argue that White deserves recognition for inventing Tabasco sauce. There’s speculation that McIlhenny, also from Louisiana, may have obtained his pepper seeds from the colonel. The McIlhenny family disputes this, citing key differences, such as White’s lack of fermentation. Regardless of its true origin, McIlhenny is credited with transforming the recipe into a global phenomenon.

Sriracha creator David Tran at his California factory. | David McNew/GettyImages

Sriracha creator David Tran at his California factory. | David McNew/GettyImagesSriracha is another iconic name in the hot sauce industry. The version popular in the U.S., with its green cap and rooster logo, was developed by David Tran, the founder of Huy Fong Foods.

Tran, born in Vietnam, began selling his chili sauce in 1975. By the end of the decade, he and his family escaped Vietnam aboard the Taiwanese freighter Huey Fong, meaning “gathering prosperity.” In the U.S., Tran resumed selling his hot sauce, catering to Southeast Asian immigrants seeking a familiar flavor. His recipe was inspired by a hot sauce from Si Racha, Thailand, blending red jalapenos with vinegar, sugar, and garlic to create a thicker, sweeter sauce than most Americans had encountered.

Huy Fong’s Sriracha sauce enjoyed steady success for years before skyrocketing in the mid-2000s. During the 2010s, its branding appeared on everything from potato chips to beer to cars. While the Sriracha craze has somewhat subsided, it remains America’s third favorite hot sauce, even surpassing Tabasco.

The Scoville Scale

The heat of pepper-based products is measured using a specialized scale. Pharmacist Wilbur Scoville developed the Scoville Heat Units in 1912 while working on a heat-inducing ointment.

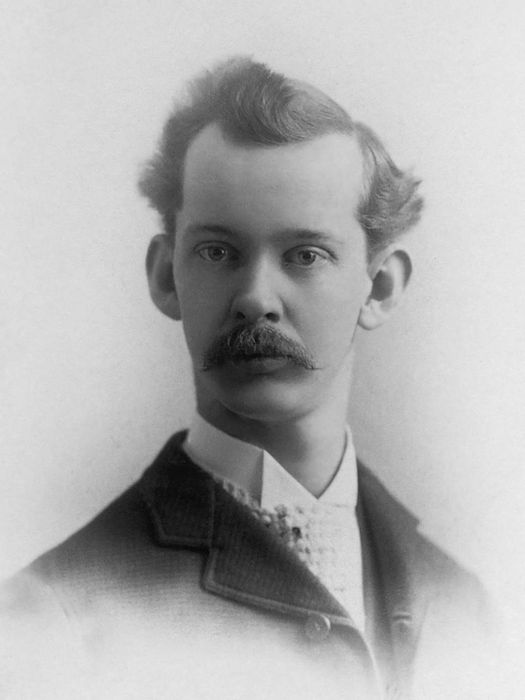

Wilbur Scoville. | Wikimedia Commons // Public Domain

Wilbur Scoville. | Wikimedia Commons // Public DomainOriginally, SHUs determined how much a spicy food needed to be diluted to eliminate its capsaicin content. Today, scientists typically use high-performance liquid chromatography to measure a product’s heat level. Tabasco sauce ranges between 2500 to 5000 SHUs, while Mad Dog 357 Plutonium No. 9—potentially the world’s hottest sauce—reaches a staggering 9 million Scoville Heat Units.

If you ever explore the upper limits of the Scoville Scale or find yourself on a show like Hot Ones, dairy can offer some relief. Casein, a protein found in milk, binds to capsaicin and helps wash it away from your taste buds.

Another option is to build a tolerance for spicy foods. By regularly exposing your taste buds to capsaicin, you can reduce their sensitivity. Experts suggest gradually incorporating spice into your diet until it becomes a regular part of your meals. However, beyond a certain heat level, only time can soothe your mouth.

This story was adapted from an episode of Food History on YouTube.